In the winter of 1961, Lucio Fontana arrived in New York and looked up. What he saw would change the course of his work forever.

In the winter of 1961, Lucio Fontana arrived in New York and looked up. What he saw would change the course of his work forever.

October 16, 2025

In the winter of 1961, Lucio Fontana arrived in New York and looked up. What he saw would change the course of his work forever.

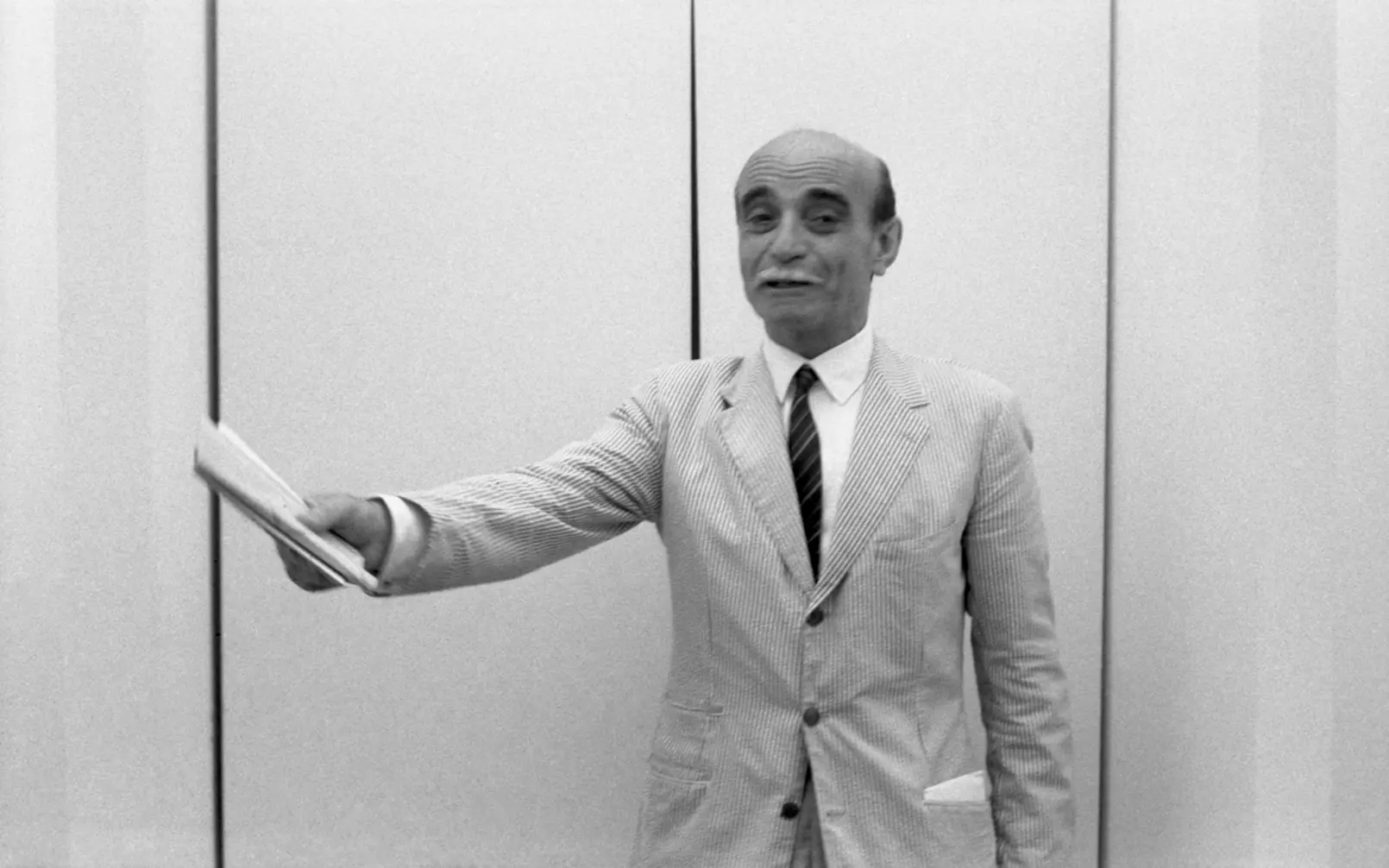

When Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana first encountered Manhattan’s skyline in November 1961, he was captivated not by the cold, but by the soaring structures slicing through the clouds, monoliths of steel and glass shimmering with light. The scale of modernity struck him with visceral force. Amid this vertical metropolis, Fontana conceived what would become one of his most groundbreaking series: Metalli.

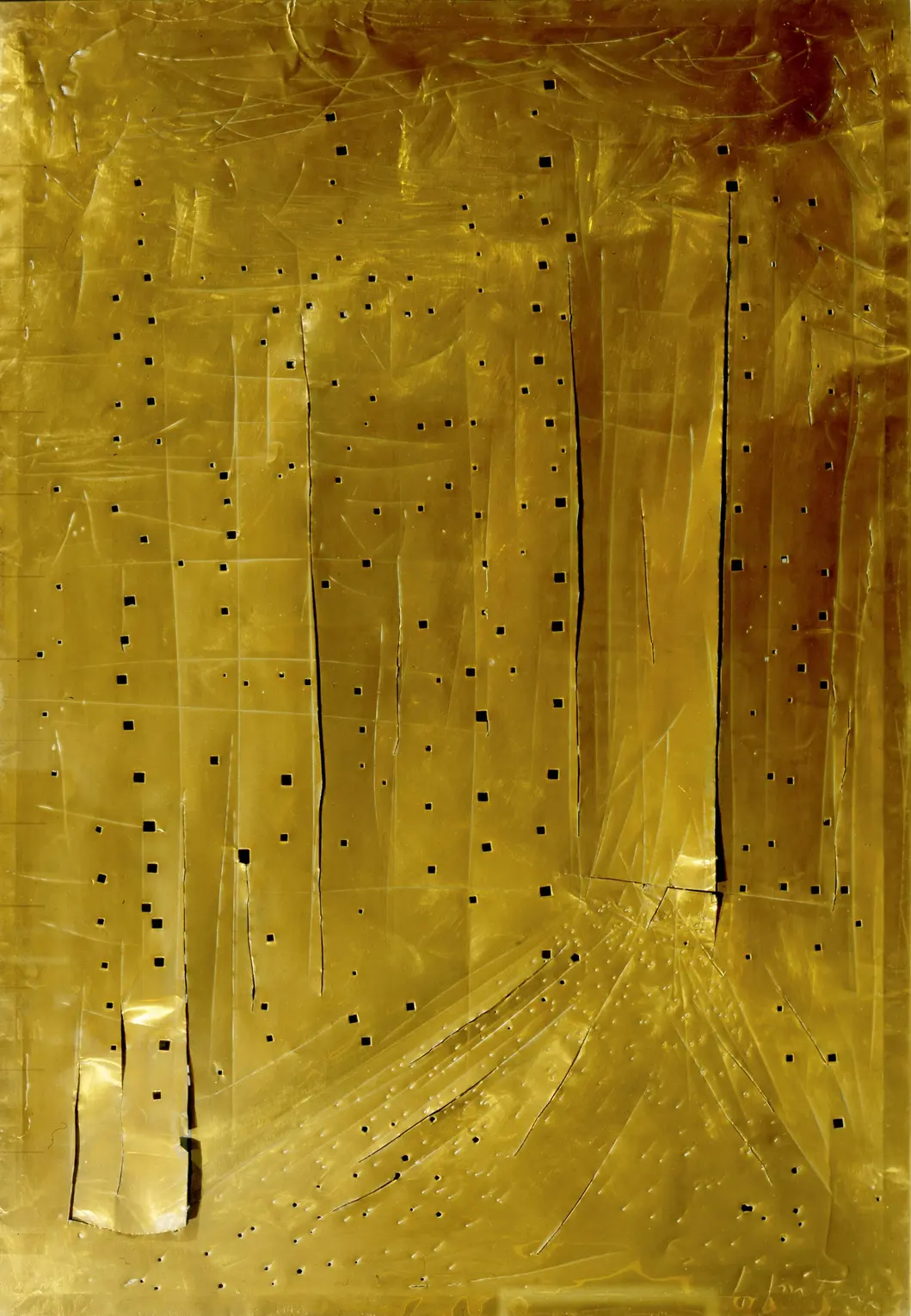

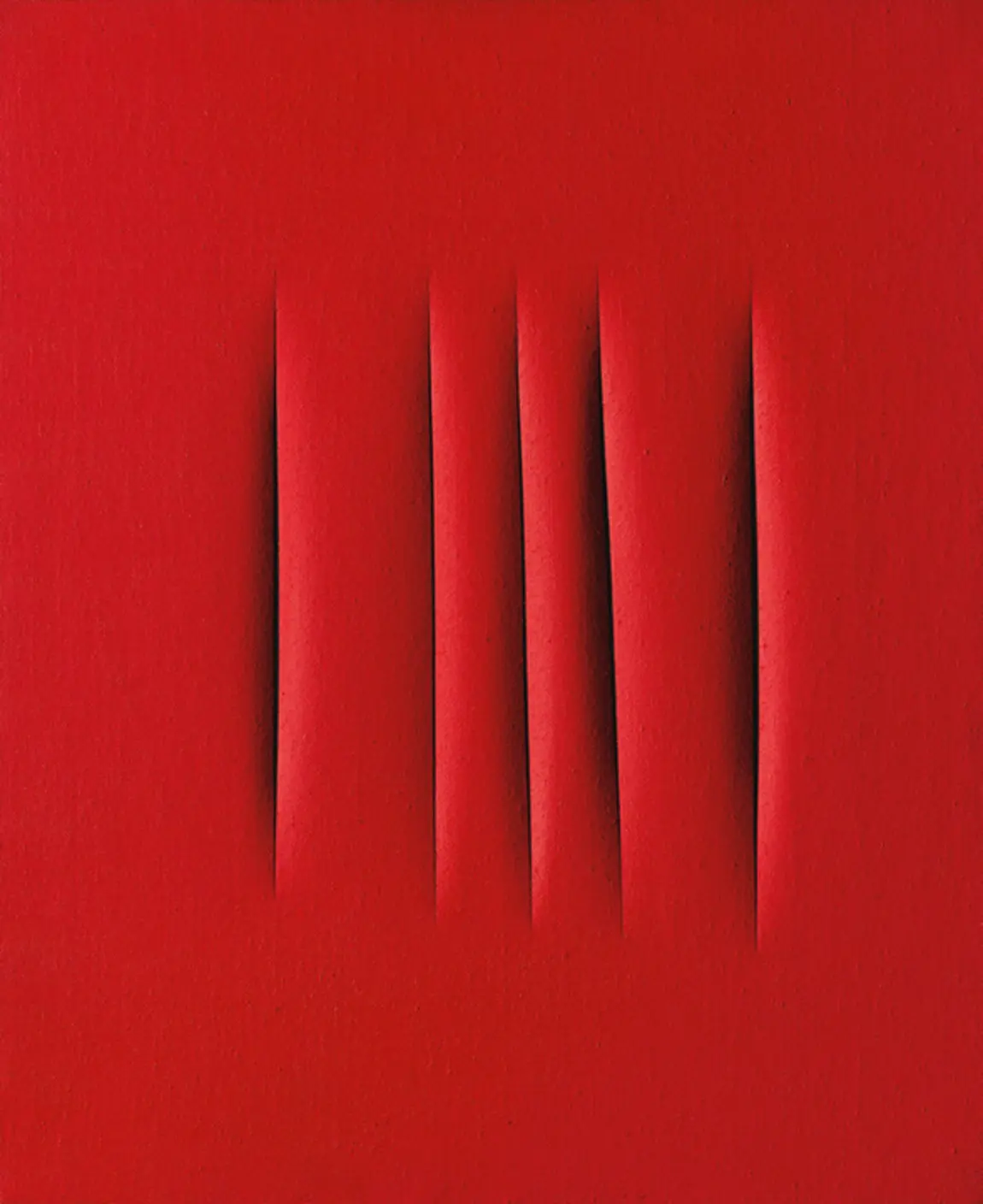

Departing from canvas entirely, Metalli embraced metal as medium and message. Fontana translated his iconic cuts and punctures into copper and aluminum, employing hand tools — awls, punches, chisels, to carve violence into surface.

These gashes were not pristine but raw, jagged, deliberately imperfect. The energy was architectural: “Sometimes scratching them vertically to convey the idea of skyscrapers, sometimes puncturing them with a metal punch,” he later explained. These works represented not just a formal evolution but a conceptual rupture, a bid to open new spatial dimensions. “I do not want to make a painting,” he declared. “I want to open space, create a new dimension.”

By 1965, Fontana's spatial experimentations expanded further, fueled by the era’s cosmic imagination. It was the year Soviet astronaut Alexei Leonov performed the first spacewalk and NASA’s early images of Mars reached Earth. Fontana, working in his Milan studio, followed the developments obsessively. In response, he created Concetto Spaziale, a monumental copper diptych. Its radiant orange hue mirrored Martian terrain, while the surface, pierced and warped, evoked craters from another world.

The work was soon acquired by Mario Bardini, Fontana’s confidant, collector, and creative partner. Their correspondence reveals the emotional undercurrent of the piece. “New York is more beautiful than Venice!” Fontana once wrote Bardini. “The skyscrapers of glass look like great cascades of water that fall from the sky!” Their dialogue was both artistic and architectural. Bardini’s acquisition was more than patronage — it was a continuation of a shared spatial vision.

In Bardini’s villa in Varigotti, northern Italy, the Concetto Spaziale diptych found a striking home: above the fireplace. But it wasn’t simply hung—it was integrated. Bardini, an architect, treated the work as structural, building it into the heart of the room. The copper planes became part of the architecture, blurring boundaries between art and environment.

This fusion was no accident. Bardini and Fontana had collaborated on site-specific works throughout the 1950s and '60s, slicing through walls and ceilings, integrating spatial concepts into physical dwellings. The placement of Concetto Spaziale above the hearth was a final, poetic gesture: a fireplace transformed into a sculptural altar, where art was not merely viewed, but inhabited.

The diptych remained there for decades, a totem of shared vision and artistic intimacy, until Bardini’s death in 2005.

The next chapter in the diptych’s journey began in 2004. In London, film producer and design collector Ronnie Sassoon discovered it in a Sotheby’s catalogue. “I saw a photograph of the Fontana and simply had to acquire it,” she recalls. Though searching for one of his terracotta Natura sculptures, she was transfixed by the elemental power of copper and steel.

Already a devoted Fontana collector, Sassoon owned a canvas featuring seven tagli (cuts) and a rare La fine di Dio. But this work—aggressive, industrial, glowing—felt different. It was her first Fontana in color, and it shifted the palette of her collection.

Sassoon installed the piece in her Soho loft, flanked by 19th-century fire escape windows, suspending it in space. “Fontana once said he was more interested in what lay beyond the surface,” she says. “So I thought he might approve.”

Years later, during the pandemic, Sassoon relocated to Cincinnati and brought the diptych with her. In her Carl Strauss-designed modernist home, it now hangs beneath a horizontal window, where sunlight refracts across its copper skin. The work comes alive throughout the day, animated by light and shadow—a living, breathing element in the space it occupies.

Fontana’s radical gestures once scandalized critics, also baffled them, because his domain is considered both modernism and post-modernism. Today, they feel uncannily prescient. In a fractured world —defined by digital disruption, political schism, and environmental collapse, his work speaks to rupture as renewal. His cuts are invitations: to look deeper, to question limits, to see space not as emptiness, but as possibility.

Sassoon admits that she once saw the Metalli series as secondary to Fontana’s canvases. Two decades later, her view has shifted. “It’s one of the most important works I’ve ever owned,” she says. Its presence, both architectural and philosophical, continues to challenge, inspire, and transform. Much like the city that first birthed it, the diptych is a mirror of ambition, vision, and space unbound.