Yves Saint Laurent stitched Mondrian’s grids into skirts, slipped Pop Art’s mischief into seams, let Picasso pirouette in silk, draped Matisse’s joy like confetti, and coaxed Van Gogh’s sunflowers to bloom on shoulders

Yves Saint Laurent stitched Mondrian’s grids into skirts, slipped Pop Art’s mischief into seams, let Picasso pirouette in silk, draped Matisse’s joy like confetti, and coaxed Van Gogh’s sunflowers to bloom on shoulders

November 19, 2025

Few couturiers in history have woven such an intricate, enduring dialogue between fashion and fine art as Yves Saint Laurent. His career, spanning decades of cultural and creative revolutions, was marked by a fearless willingness to draw directly from the world’s greatest painters and movements. For Saint Laurent, art was not a distant, untouchable museum treasure. It was a living language, one that could be translated into silhouettes, textiles, and embroidery with the same rigor and reverence as a master’s brushstroke.

From modernist abstraction to Pop Art exuberance, from cubist geometry to post-impressionist vibrancy, Saint Laurent’s collections became a bridge between haute couture and the history of art. Each series did more than reference paintings; it transformed them into wearable forms, elevating fashion into a parallel gallery of visual culture.

In 1965, Yves Saint Laurent sent six dresses down the runway that looked like they had stepped straight out of a modern art gallery. His Autumn/Winter Mondrian Collection took the iconic black grids and primary color blocks of Piet Mondrian, the star of the Dutch "De Stijl" movement, and turned them into haute couture with architectural precision. These were no lazy prints: each block of pre-dyed wool jersey and silk was meticulously pieced together with invisible seams, creating a flawless, walking canvas.

De Stijl, literally “The Style” in Dutch, was the early 20th century’s answer to visual clutter. Led by Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, it shaped painting, architecture, typography, and design, influencing everything from Bauhaus chairs to the clean lines of International Style buildings. Saint Laurent’s dresses captured that same disciplined harmony. While the 1960s fashion world still adored embellishment, these pieces offered something startlingly fresh: minimalism with the complexity of a symphony. They blurred the line between “highbrow” art and “lowbrow” accessibility. It worn by society women, splashed across the cover of French Vogue, and, in America, copied in department stores faster than a Beatle mania bob cut.

Diana Vreeland called the collection “genius,” and rightly so. The Mondrian dress was modernist philosophy that could zip up the back. It proved that art could step off the wall and onto the street without losing its integrity, making it one of the most recognizable, influential, and quite literally-one of the most copied works of fashion art in history.

If Mondrian’s 1965 dresses were the architectural symphony of couture, Yves Saint Laurent’s Autumn/Winter Haute Couture 1966 Pop Art Collection was its rock concert: loud, colorful, and unapologetically modern. Moving from European restraint to American cultural exuberance, Saint Laurent drew from Tom Wesselmann’s bold, ironic paintings of lips, nudes, and everyday consumer goods, translating them into dresses that felt like walking billboards of wit and style.

Where Mondrian’s lines were disciplined, Pop Art was theatrical. Saint Laurent’s dresses burst with vivid blocks of color, playful graphic motifs, and daring cutouts that mimicked Wesselmann’s flat yet seductive imagery. Two standout designs featured strategically placed openings layered over contrasting fabrics, bringing Pop Art’s playful subversion to life. These garments carried the same visual punch as an Andy Warhol soup can, but in silk and satin rather than paint.

This fusion gave haute couture a jolt of youthful energy, making it as accessible in spirit as street fashion while maintaining meticulous craftsmanship. It was couture that spoke in the same visual language as the 1960s art scene: bold, ironic, and impossible to ignore. In doing so, Saint Laurent cemented fashion’s place in the cultural avant-garde, proving that a dress could be as much a piece of art history as a painting on a gallery wall.

In 1979, Yves Saint Laurent turned his creative spotlight on Pablo Picasso and the theatrical magic of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, drawing inspiration from Parade - the 1917 ballet for which Picasso designed sets, costumes, and a monumental stage curtain. The result was a collection where couture became performance, garments choreographed in both shape and color.

“From that moment, I built my collection like a ballet. I embroidered on Picasso [...]. " - Yves Saint Laurent

Saint Laurent mined Picasso’s “softer cubism” and the emotional depths of his Blue and Rose Periods, translating them into silhouettes with shorter hems, lower necklines, and broader shoulders. “I feel artistic joy,” he admitted, likening his work to painting directly with fabric. Flat colors replaced blended tones, seams became brushstrokes, and each piece carried a theatrical rhythm.

Some looks paid explicit homage to Picasso’s canvases. A navy-blue jacket mirrored the one in Nusch Éluard’s Portrait (1937) with near-perfect fidelity. A long evening dress combined a black silk velvet bodice with a duchess satin skirt, embroidered in patchwork appliqués by Brossin de Méré. A satin guitar and silk ottoman appeared amid shapes evoking Picasso’s cubist works, turning the garment into a walking collage.

To Saint Laurent, Picasso was “genius in its purest form… baroque,” a creator with infinite trajectories. In this collection, he mirrored that spirit—dissolving boundaries between costume and couture, art and life—until every runway step felt like part of a ballet where fabric was the dancer, and color the music.

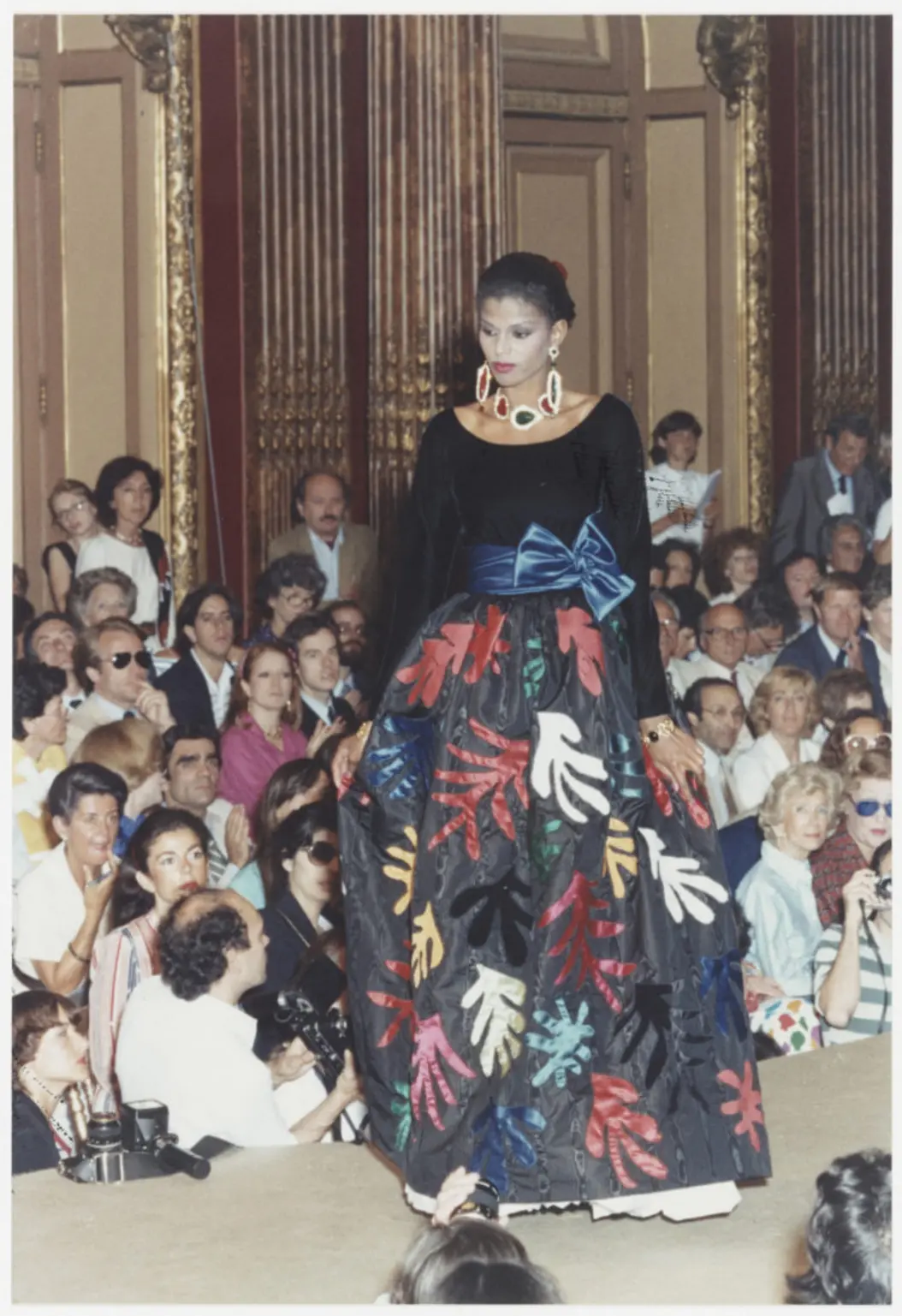

n 1981, Yves Saint Laurent transformed the runway into a gallery where Henri Matisse’s joyful Fauvism met Fernand Léger’s disciplined Cubism. If Matisse painted with the freedom of a dancer and Léger constructed with the precision of an architect, Saint Laurent became the choreographer who allowed both to move across a woman’s body.

From Léger came Cubist discipline, most vividly in an evening gown inspired by his The Polychrome Fleur (1936). Like the painting, the gown was formed from bold panels of red, cobalt, yellow, and black, cut into interlocking geometric pieces. Each seam was intentional, framing the colors so the wearer’s body became a three-dimensional canvas - Cubism brought to life in silk and thread.

From Matisse came Fauvist exuberance, echoing works like La Gerbe (1953). Velvet skirts exploded in patchwork, with multicolored satin appliqué leaves cascading over the fabric like his cut-out forms. These flat, vivid color blocks, unapologetically bold and unblended, carried the same emotional intensity Matisse poured into his paintings - more about feeling than formality.

Displayed at the Hôtel Inter-Continental alongside the original artworks, the gowns blurred the line between wall and wardrobe. For Saint Laurent, it was proof that couture, like modernism, could be both structure and soul, and that the runway could serve as a living museum where fabric danced with the same vitality as paint.

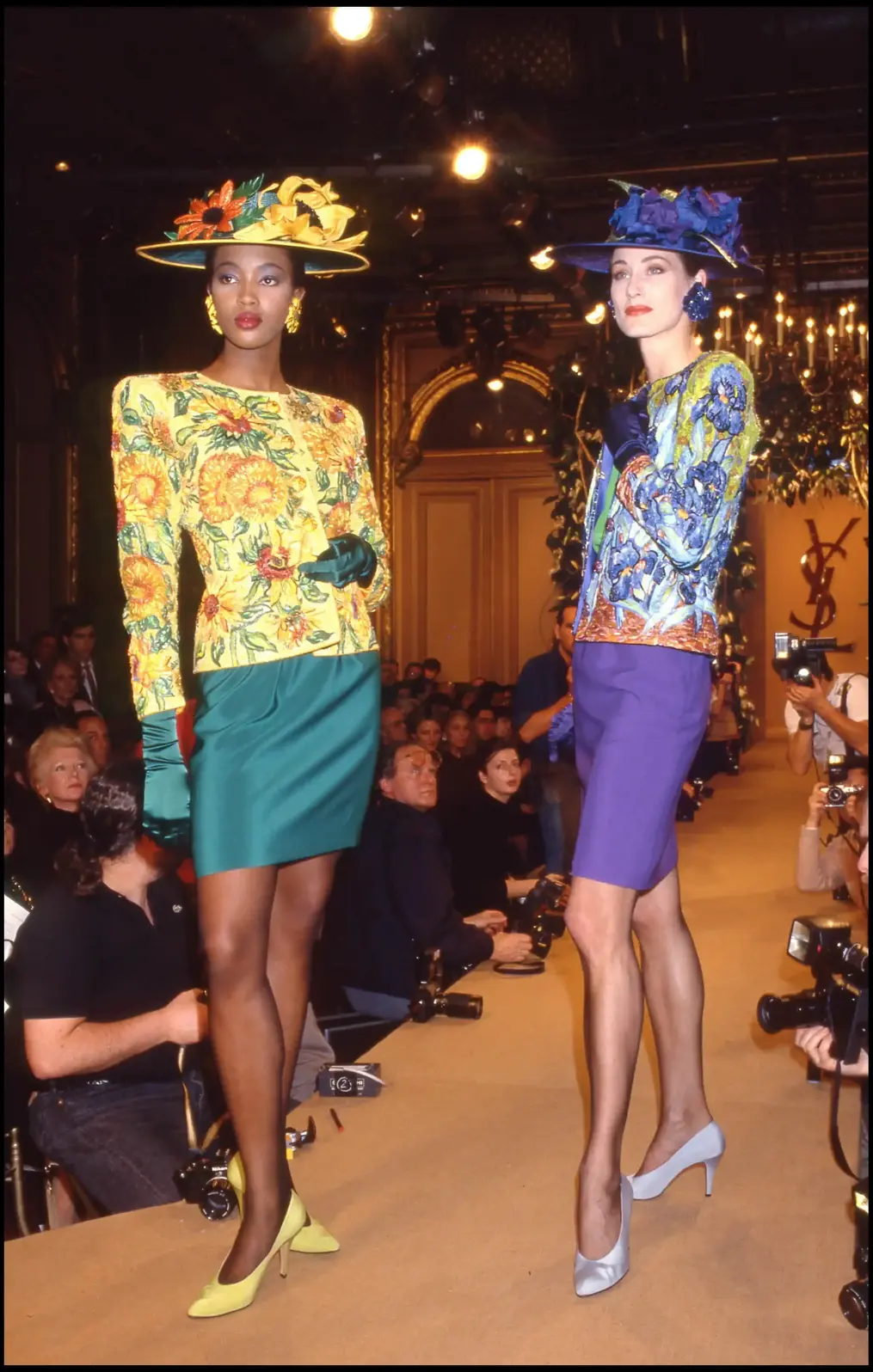

If Mondrian was structure, Pop Art was energy, and Matisse was painterly form, then Yves Saint Laurent’s Spring–Summer 1988 homage to Vincent van Gogh was pure emotion—devotion translated into thread. Drawing from Irises and Sunflowers, Saint Laurent, alongside the master embroiderers at Maison Lesage, transformed fabric into gardens that seemed to have blossomed straight from Van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist canvases.

Van Gogh’s style was never about precise realism. t was about feeling, about making the world pulse through thick, swirling brushstrokes. Saint Laurent mirrored this through embroidery, layering sequins, beads, pearls, and ribbons like strokes of paint. The Irises jacket, one of his most literal interpretations, shimmered with overlapping sequin petals, while blue bugle beads traced leaves with almost botanical precision. Its interplay of light and substance revealed a couturier’s connoisseurship, turning fabric into a textured painting.

The Sunflowers jacket blazed in yellow organza, glass beads, rocaille, and satin, so densely embroidered it became sculptural. Paired on the runway with a green crepe skirt and a bouton d’or satin blouse, it vibrated with life, as if each bloom had leapt from Van Gogh’s 1889 canvas to embrace the wearer. Sequins and pearls were arranged to mimic brushstrokes, creating a pictorial effect so vivid that Vogue called it the “coup de grâce” (the finishing blow) of the collection.

Each jacket required over six hundred hours of work, with only four Sunflowers pieces ever made, which rarities akin to owning a masterwork. This made the Sunflower Jacket become one of the most expensive haute couture masterpieces ever created, which was sold for approximately $420,000 to the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia in 2019. When Naomi Campbell walked the runway in them, she was wearing a living Van Gogh, proving that in her right hand, a needle could rival the power of a paintbrush.

“This is one of François Lesage’s masterpieces.”- Camille de Foresta, a specialist at Christie's. “The beading techniques used to create it are the pinnacle of haute couture.” - she added.

Tracing these collections together, a clear through-line emerges: Saint Laurent was not merely “inspired” by art but entered into a reciprocal relationship with it. Each season that engaged with an artist or movement did so with specificity and integrity, whether in De Stijl's severe lines, Wesselmann’s playful provocation, Picasso’s performative cubism, Matisse’s lyrical shapes, Léger’s modernist geometry, or Van Gogh’s brushwork. This was not decorative borrowing. It was translation, from static visual language to dynamic. His clothes allowed women to wear modernism, walk through pop culture, and embody the spirit of post-impressionism.

Saint Laurent’s work also shifted the conversation about what fashion could be. It positioned haute couture alongside fine art in cultural value, set new benchmarks for craftsmanship, and inspired future designers to see galleries and ateliers as parallel creative spaces rather than separate worlds.

In the grand gallery of 20th-century style, Yves Saint Laurent’s artistic collections remain some of its most enduring exhibits, where fabric becomes pigment, seams become brushstrokes, and every runway becomes a canvas.