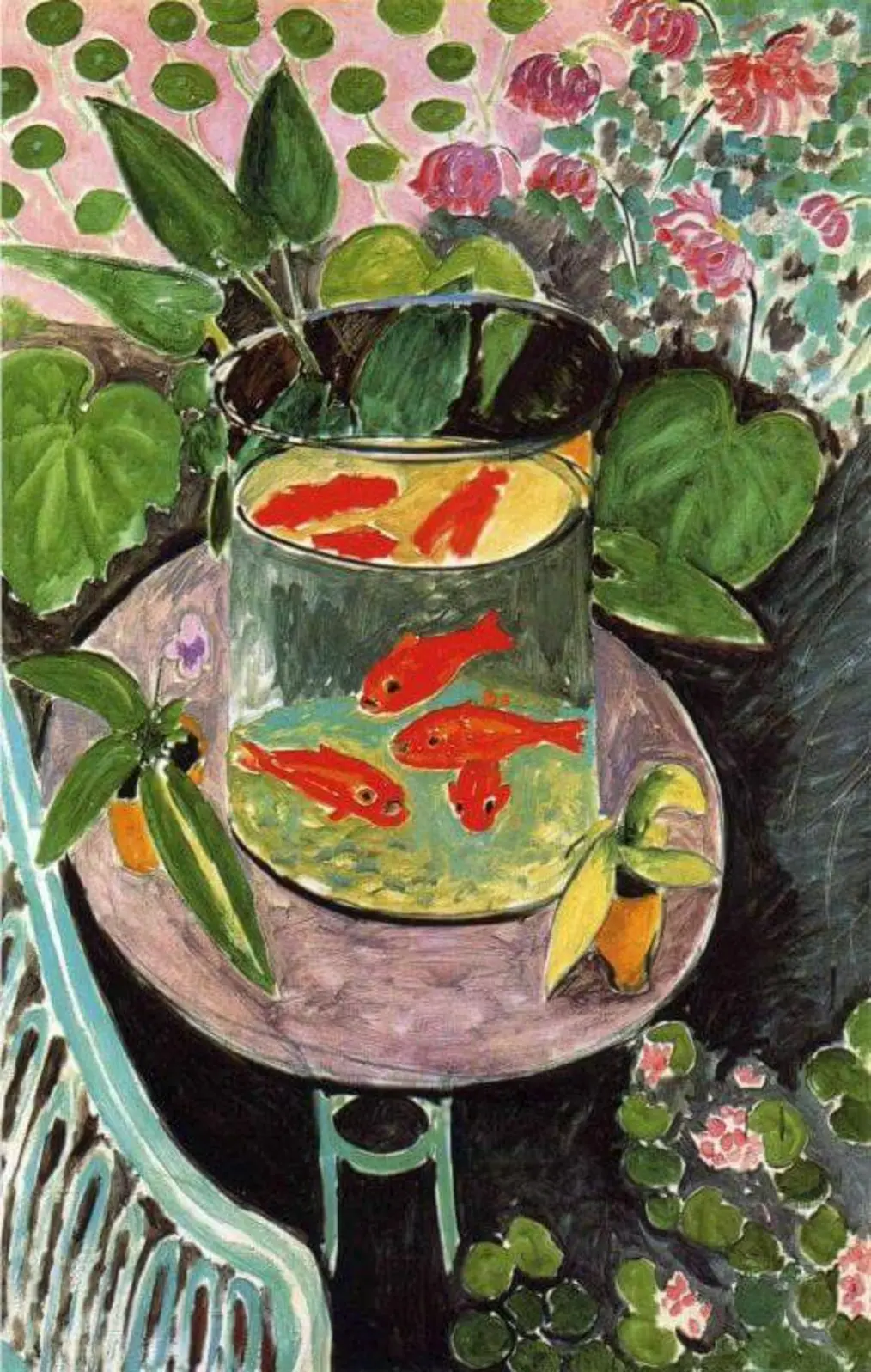

"I wouldn't mind turning into a vermilion goldfish." – Henri Matisse

"I wouldn't mind turning into a vermilion goldfish." – Henri Matisse

October 16, 2025

"I wouldn't mind turning into a vermilion goldfish." – Henri Matisse

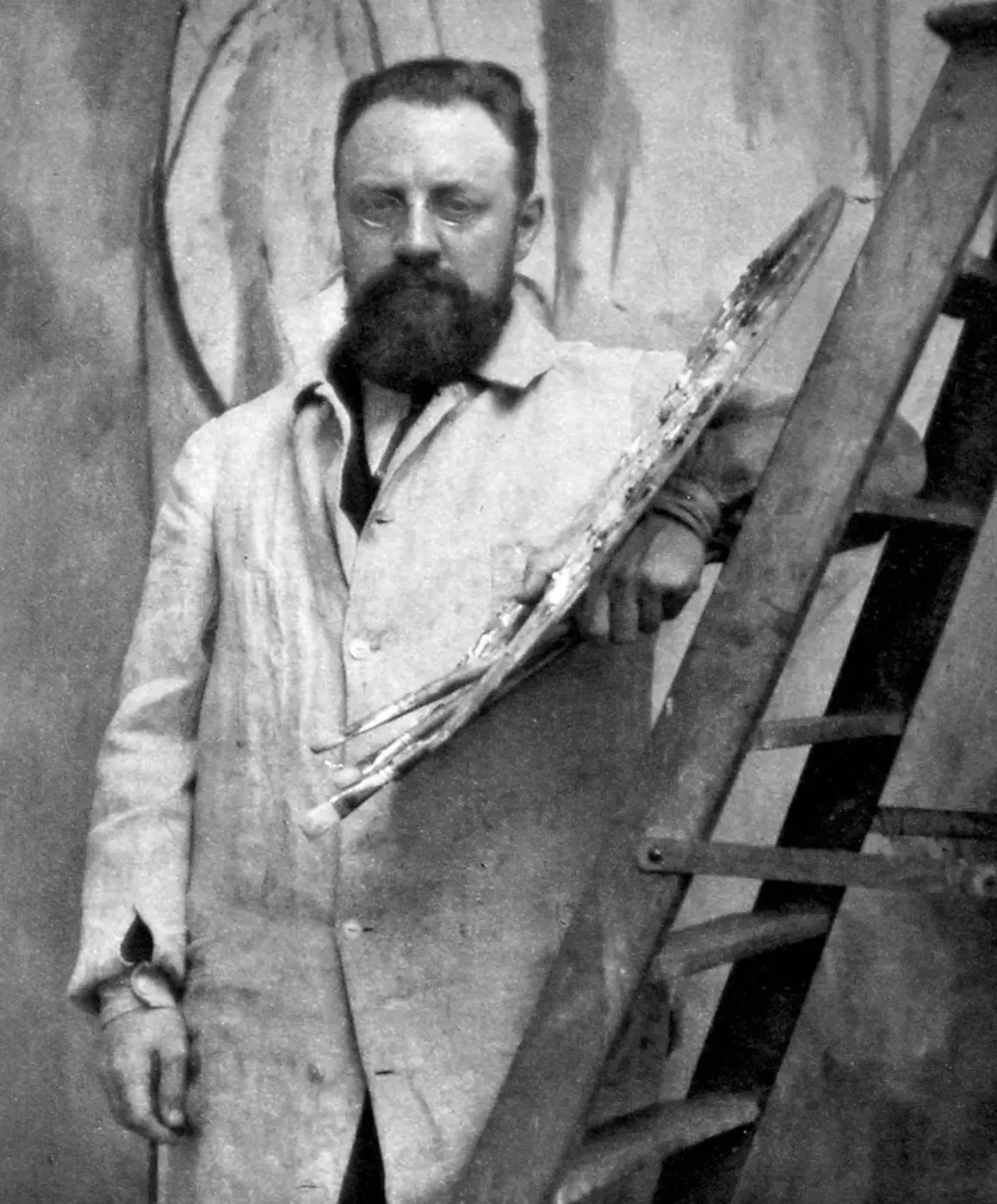

At 20, Matisse suffered from severe appendicitis. His mother gifted him a paint box during his convalescence, which ignited a passion for art, leading him to abandon law to pursue art, his "kind of paradise." He initially trained under Gustave Moreau, and while influenced by Old Masters, he was profoundly impacted by the work of Paul Cézanne. This early, disciplined period of mastering fundamentals laid the groundwork for his later, revolutionary style.

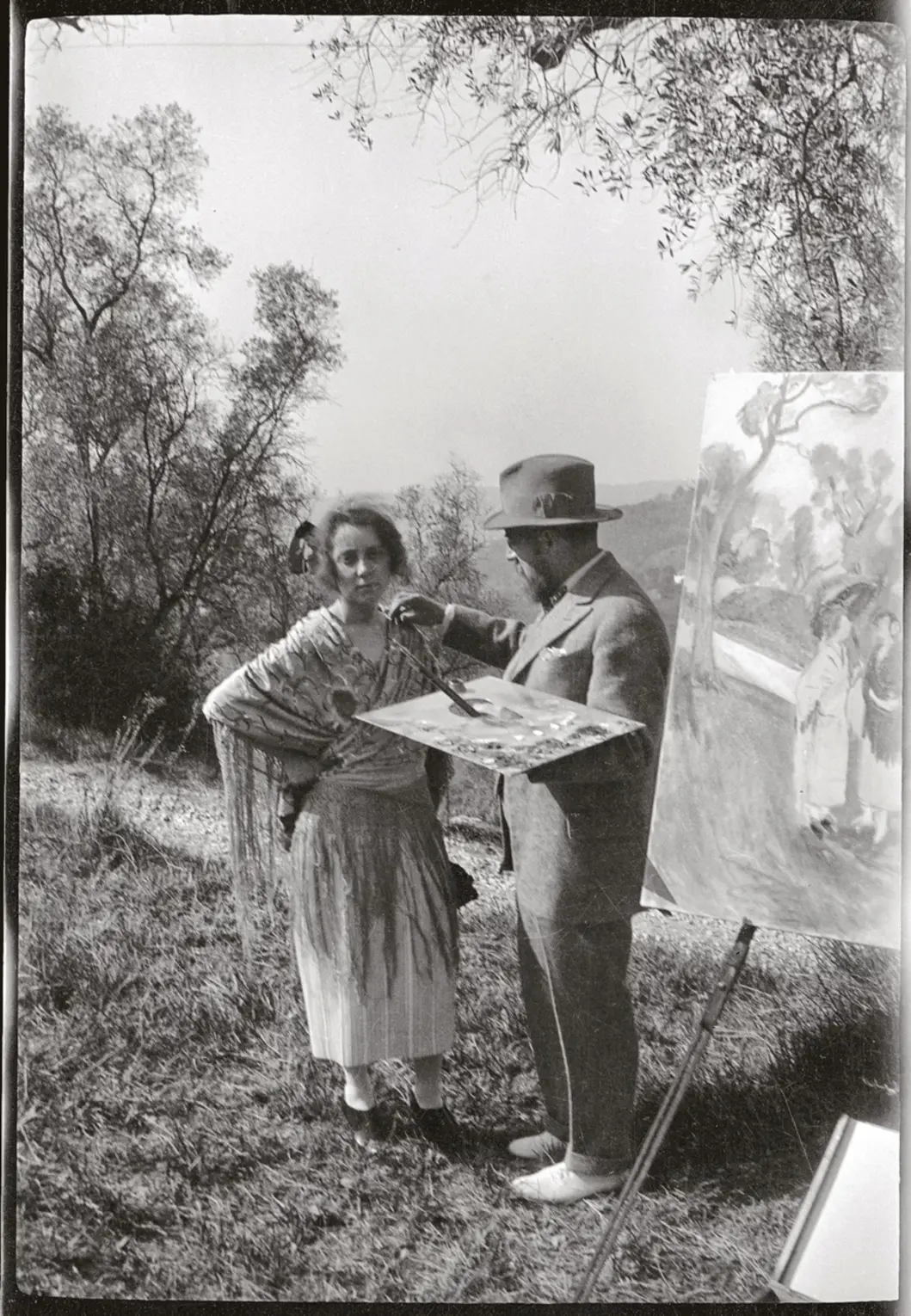

In the early 1900s, Matisse's travels to Algeria, Spain, and Morocco profoundly shaped his style. Henri Matisse's art was significantly influenced by his exposure to Islamic art and culture, particularly during his travels to Algeria and Morocco. This influence is evident in his use of bold, flat colors, decorative patterns and a shift towards abstraction.

In 1904, Matisse studied with painter Paul Signac, learning new techniques for applying paint and using color. These artists often worked with the Chevreul color wheel, a chart which helped many artists, including Van Gogh and Matisse, use complementary colors. Matisse became a master at using Chevreul's system to great effect in his work.

After a few decades, the brilliant yellow in paintings by Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh are slowly fading to duller, beige tones, which significantly alters their original appearance. A specific cadmium yellow pigment contains properties that cause it to oxidize when exposed to light, stripping the paint of its vibrant color and affecting countless masterpieces.

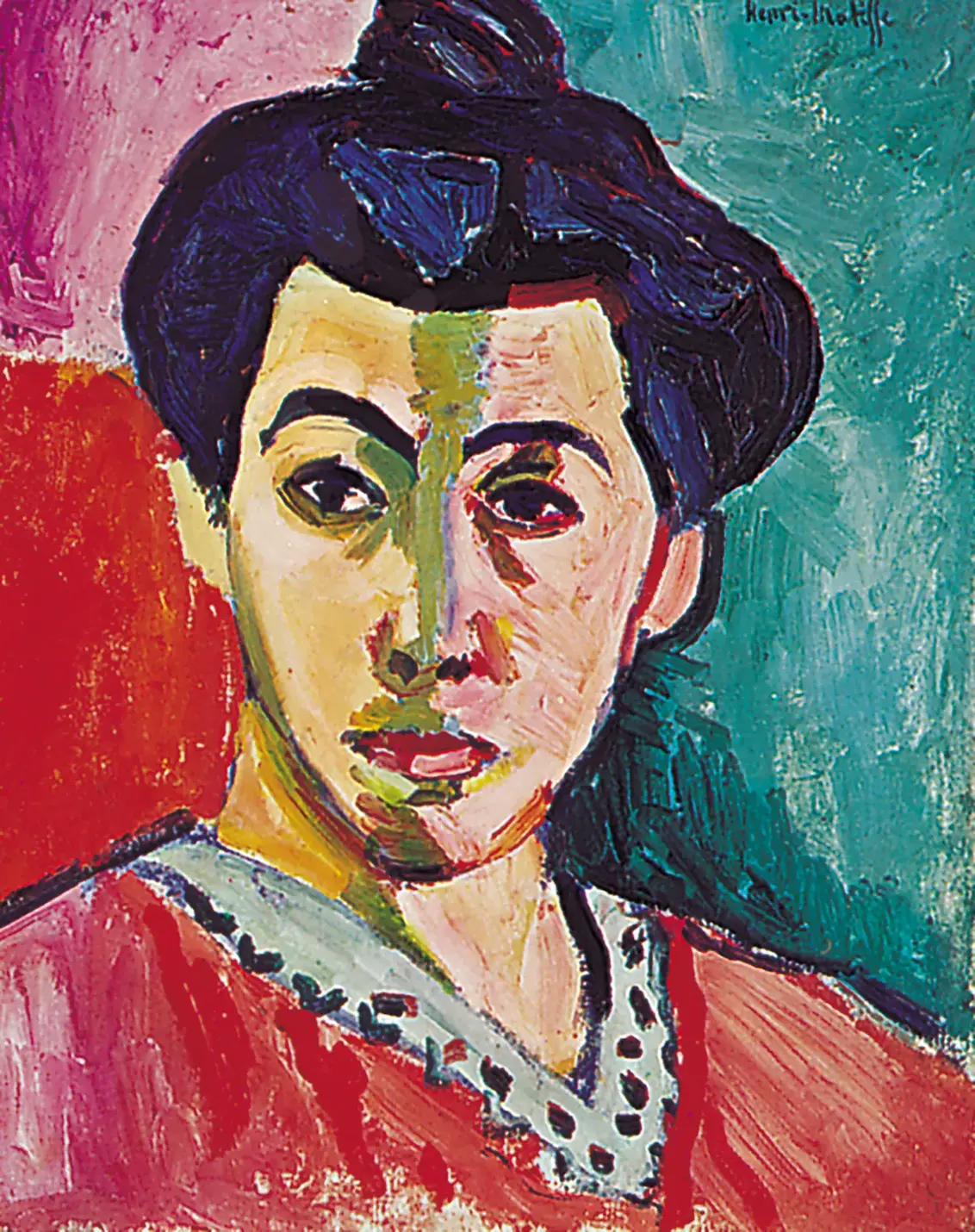

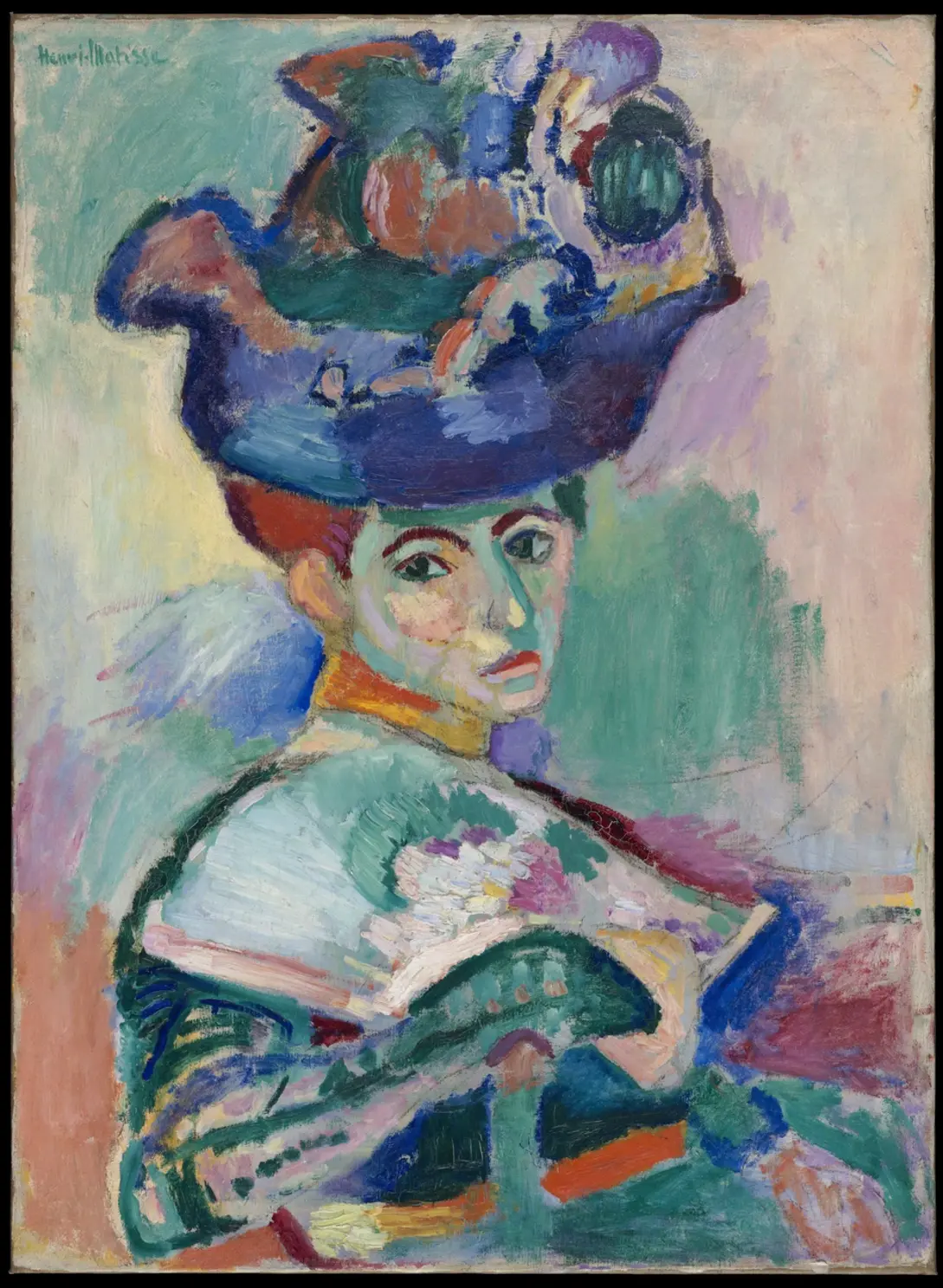

The next phase of Matisse's career triggered a seismic shift in modern art. The pivotal moment came at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in Paris, where Matisse and fellow artists like André Derain exhibited canvases that erupted with bold, non-naturalistic colors and ferocious brushwork. Upon seeing these radical paintings, the critic Louis Vauxcelles (who also coined the term Cubism) degraded the brushstrokes and the "orgy of colors" by comparing the art to a beast. The name stuck, and Fauvism, originally an insult, became a badge of honor for the artists.

Matisse's work from this era, like his celebrated Woman with a Hat, shocked the public with vibrant hues applied directly from the paint tube. The Fauvist revolution was to liberate color from its descriptive role, using it instead to convey pure emotion and create harmony. As Matisse himself said, "I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me." Though brief, this period was immensely influential, establishing Matisse as a true "wild beast" and a leader of modern art.

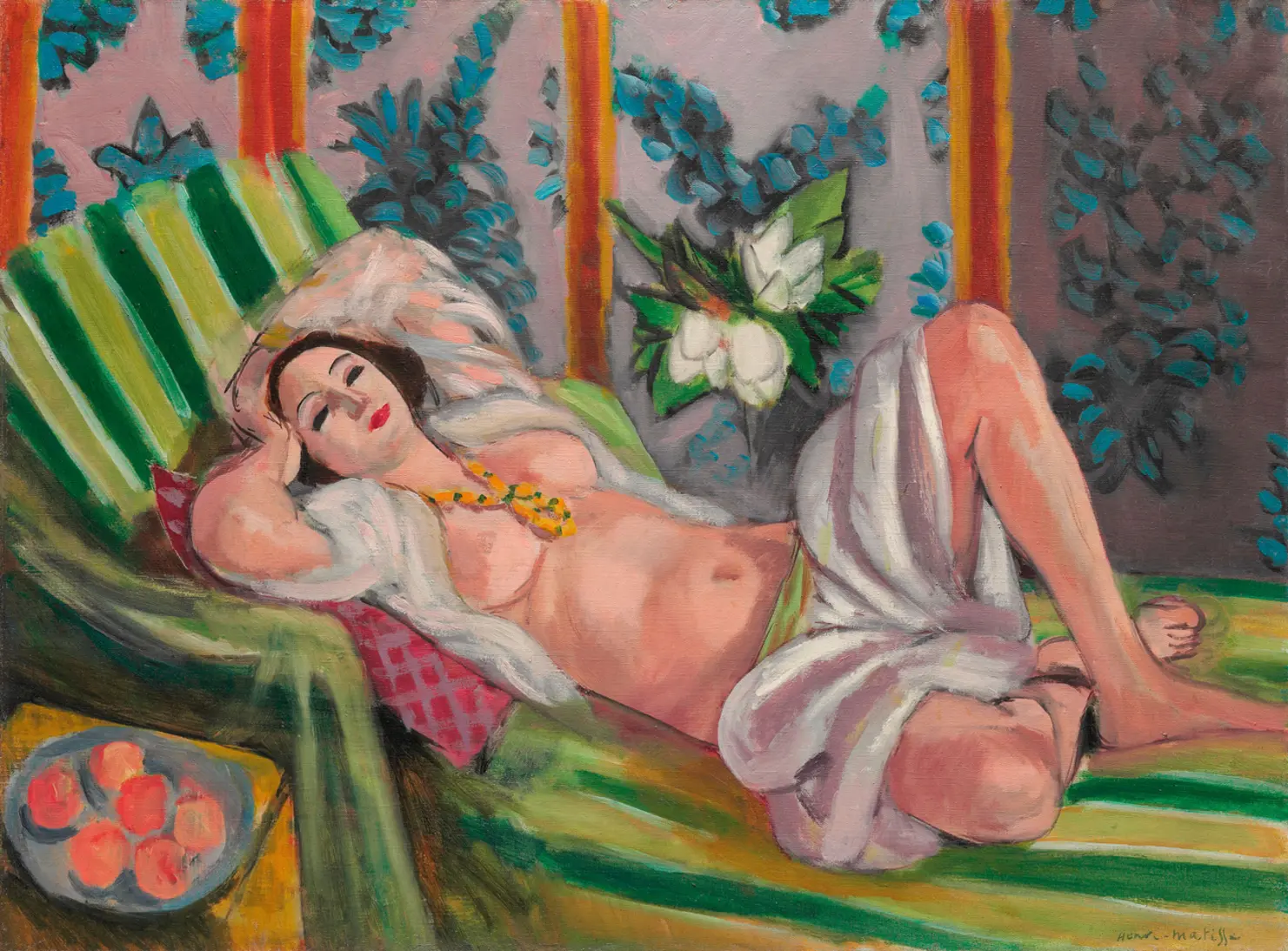

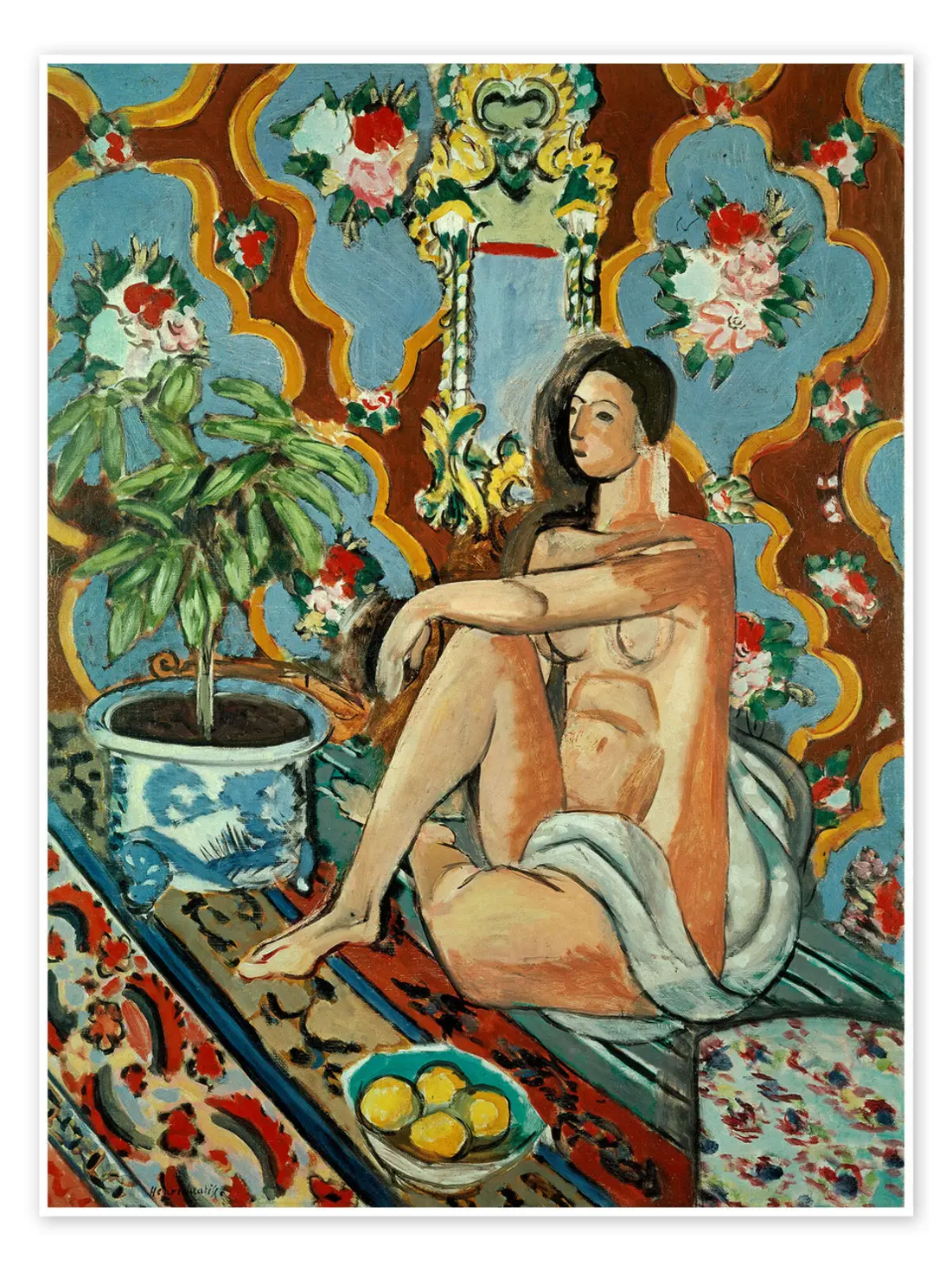

Henri Matisse moved to Nice on the French Riviera in 1917, ushering in a prolific and joyous new phase in his career. Inspired by the bright Mediterranean light and the sensuous atmosphere, he began to create paintings defined by vibrant, decorative patterns.

This period is most famous for his series of odalisques, reclining figures in lush, ornate interiors. Drawing from his travels to Morocco and his love of Islamic art and textiles, Matisse simplified forms and flattened the picture plane. He used intricate patterns and brilliant colors to create a sense of luxurious, tranquil harmony, prioritizing an "art of balance, of purity and serenity" over strict realism. Letting the art speak for itself, Matisse famously said "I have always tried to hide my efforts and wished my works to have the light joyousness of springtime, which never lets anyone suspect the labors it has cost me."

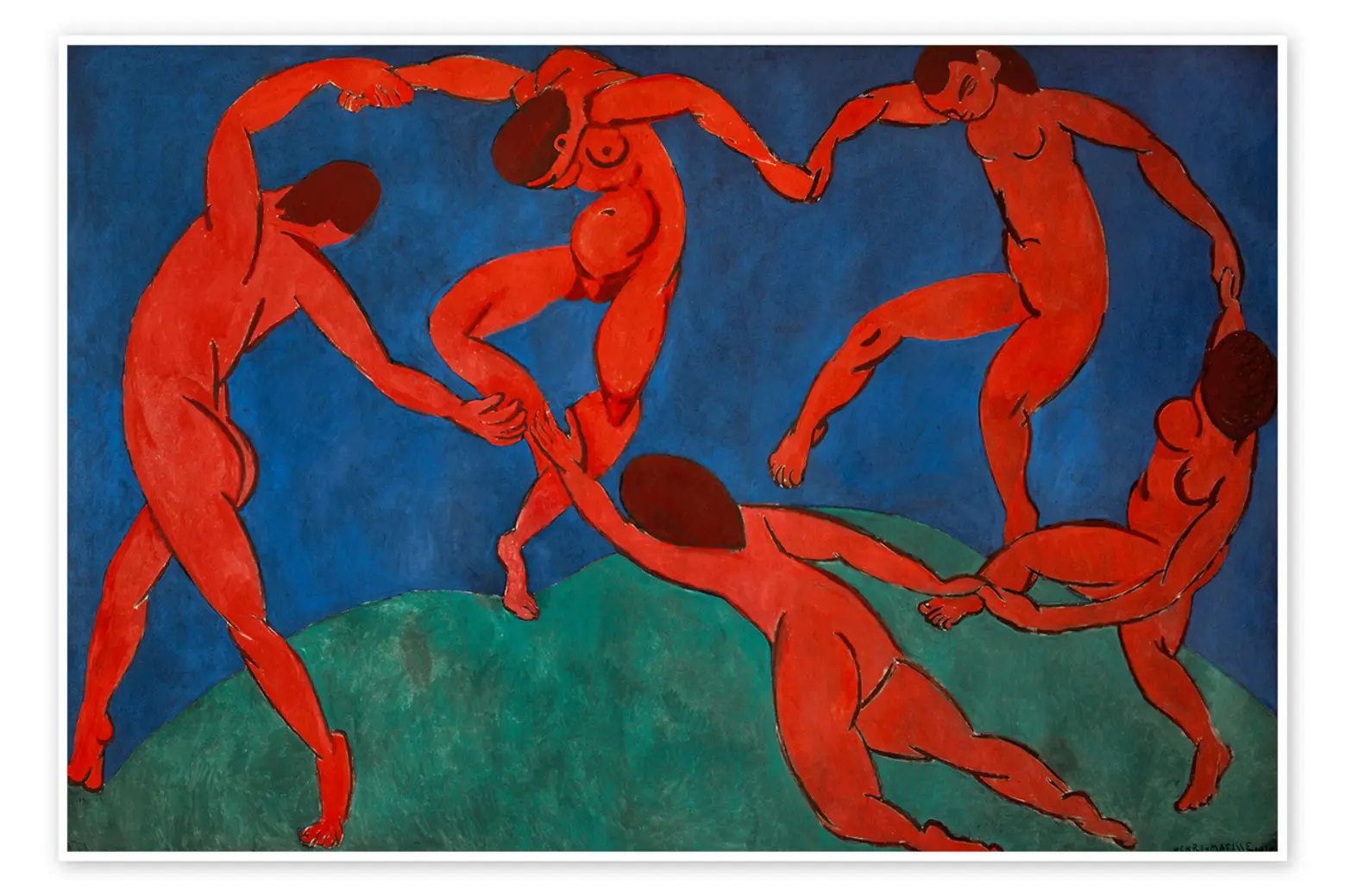

Matisse’s most powerful innovations in color came in his large-scale commissions for Russian collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. His works for Shchukin, including "Red Room," "Dance," and "Music," marked a pivotal moment in European art history. In these decorative panels, Matisse abandoned the active brushwork of Divisionism in favor of flat, organic shapes and pure, saturated color to achieve a harmonious balance.

"Red Room," originally titled "Harmony in Blue," was a radical departure. Matisse completely reworked it, making the vibrant red hue primary while the cool blues and greens receded.

In "Dance" and "Music," he embraced primitivism, using bold lines and simplified forms to create a powerful emotional effect.

He faced a new challenge with his triptych for Morozov, where he felt he needed to prove the value of his work against the rising tide of Cubism. Here, he experimented with complementary colors and even divided light into geometric shapes, perhaps reflecting the influence of his Cubist rivals. Although the commission took so long to complete that Morozov never hired him again, Matisse's dedication to his vision remained constant. His philosophy "All the colors sing together; their strength is determined by the needs of the chorus. It’s like a musical chord" guided him even when his work, such as "The Red Studio," As perplexed as audiences were by thispainting, it did not help that Matisse himself was confused by his own creation, admitting to a journalist, “I like it, but I don’t quite understand it.”

When Shchukin declined The Red Studio, he probably didn’t realize he was passing on what would become one of the most celebrated pieces by the artist he had championed.

"A picture should, for me, always be decorative". This idea of "decorative" was a point of tension, especially during World War II. His rival, Picasso, declared that "painting is not made to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of offense and defense against the enemy," a statement that may have been directed at Matisse's philosophy.

However, Matisse’s refusal to abandon his vision was seen as a powerful act, since Matisse's daughter Marguerite was captured and tortured for being a member of the French Resistance during World War II.

The writer Louis Aragon, a contemporary and fellow communist of Picasso's, praised Matisse in 1946 for his unwavering commitment. Aragon felt that Matisse's pursuit of harmony and beauty helped maintain a "radiant image of France" during a time of immense national difficulty.

When the First World War broke out, Matisse was desperate to enlist but was rejected due to a weak heart. During the war, he embarked on large, challenging artworks.

Confined to a wheelchair, Matisse began to "draw with scissors." With the help of his assistants, he would cut shapes from sheets of paper that had been pre-painted with vibrant gouache. He then arranged these forms into dynamic compositions, some of which were monumental in scale.

Matisse fully embraced the cut-out technique in his design of the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, which he considered his masterpiece. For the chapel, he created designs for the windows, chasubles, and the tabernacle door.

His most famous cut-outs, like "The Snail" and the "Blue Nudes," are a testament to his profound inventiveness and his enduring pursuit of beauty.

Matisse continues to move, long after his death. His works are celebrated in major museums like the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which features masterpieces like "L'Algerienne" and "Still Life with Magnolia". American painter Joan Mitchell "wept with emotion" after viewing a grand exhibition of his work in Paris in 1970.

This year, from April 4, 2025, The "Matisse's Gaze of a Father" exhibition will be held at the Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris. The exhibition highlights Marguerite's role as her father's favorite muse.

Next year, from January 8 to January 10, the Grand Palais will host story telling sessions about the journey of Henri Matisse at the Grand Palais. The event is also available online.