From painting to Armani's fashion, from cinema to world-class designs, Italy has never been absent from the global cultural flow.

From painting to Armani's fashion, from cinema to world-class designs, Italy has never been absent from the global cultural flow.

November 22, 2025

Beyond the catwalks and the silver screen lies a deeper, more foundational layer of Italy’s creative genius: its unparalleled legacy in design. It is here, in the objects that shape our daily lives, that the Italian spirit finds its most profound and enduring expression. This is a world where a chair is not merely for sitting, but a manifesto of lightness; where a lamp does not simply illuminate, but sculpts the air with poetry. To travel through the landscape of Italian design is to take a journey into a national psyche that values la bella figura—the art of beautiful appearance — as much as it does inventive function. It is a culture that has consistently gifted the world with visionaries who see the extraordinary in the ordinary, transforming humble materials into icons and infusing homes with joy, curiosity, and a fearless sense of the future. We begin our exploration with the foundational giant who set this entire vibrant movement into motion.

Gio Ponti, the father of Italian modern design, was the perfect embodiment of a true all-around creator: architect, designer, lecturer, writer, and founder of Domus magazine, a theoretical platform that shaped Europe’s aesthetic discourse throughout the 20th century.

Ponti left his mark on everything from glass vases to monumental national works. “Architecture is like a dress: it must fit the person wearing it, but it must also seduce.”

Indeed, the Pirelli Tower in Milan (1961), with its slender structure and graceful stance, was described by him as an “architectural lover”—a symbol of modernity and femininity.

Ponti’s designs always radiated with joie de vivre, vibrant colors, and an expressive spirit—elements that perfectly reflected his free-spirited personality and the romantic essence of Italy.

Ponti’s Superleggera chair collection (1957), weighing only 1.7 kg—light enough to be lifted with a single finger—is a technical and aesthetic masterpiece that continues to be reproduced to this day.

Castiglioni once declared: “If you’re not curious, forget it.” For him, anything could become a source of inspiration: the Mezzadro chair from a tractor seat, lamps from car headlights, and the Arco lamp inspired by the silhouette of a streetlight.

The Arco lamp (1962), with its sweeping arching stem extending from a marble base, has been in continuous production for more than 60 years and remains one of the most replicated designs in the world.

Paola Antonelli—curator at MoMA and once his student—described Castiglioni as “a silent-film comedian: always surprising, charming, and endlessly creative.”

The Chair 4860, made of ABS plastic, is an icon of the 1960s: lightweight, stackable, and embodying an industrial, mass-culture spirit.

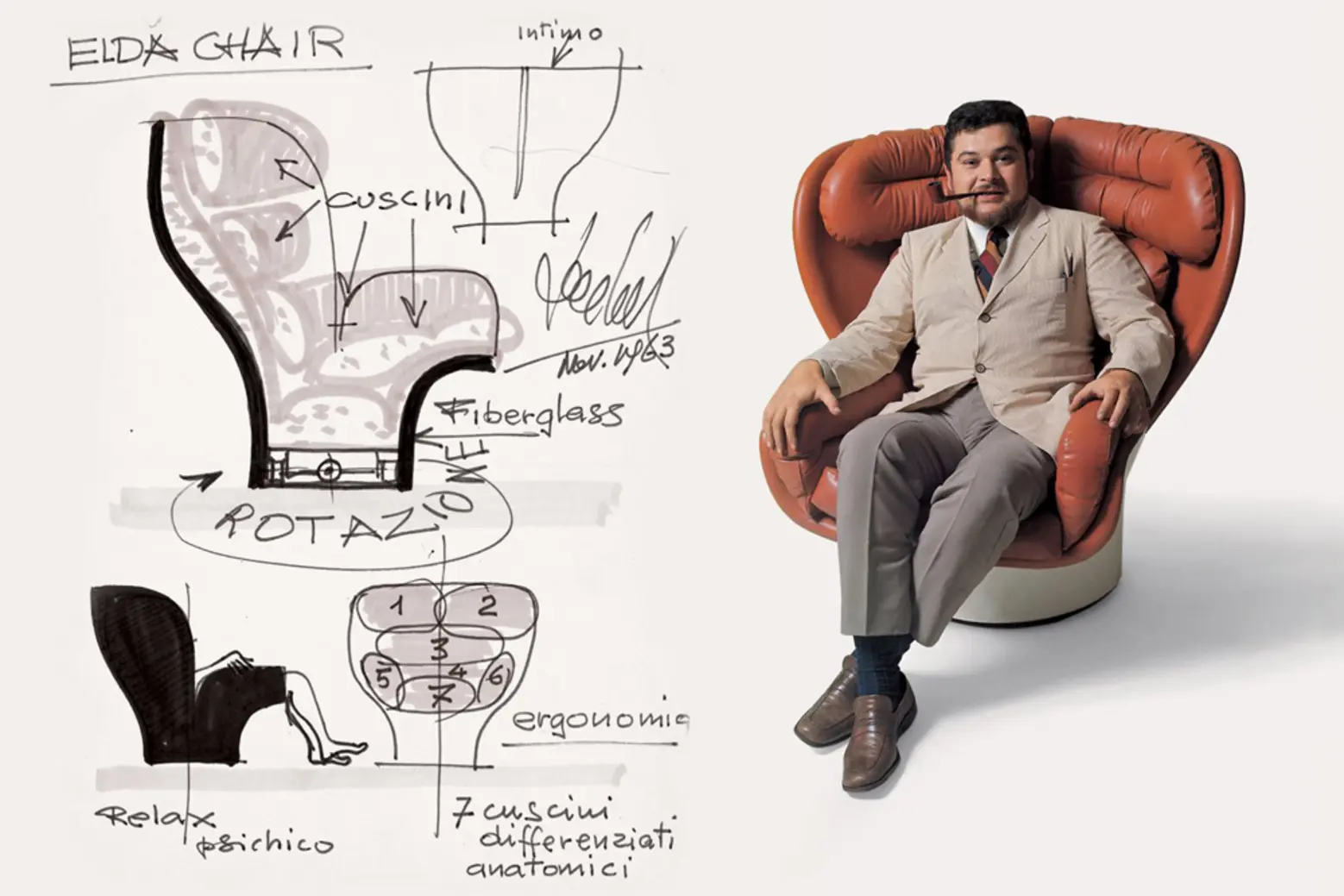

Meanwhile, the Elda Chair, with its thick enveloping leather and swivel body resembling a spaceship cockpit, has become an icon not only of design but also of science fiction cinema.

The Elda Chair has appeared in films such as The Hunger Games, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Space: 1999, becoming a futuristic icon on the big screen.

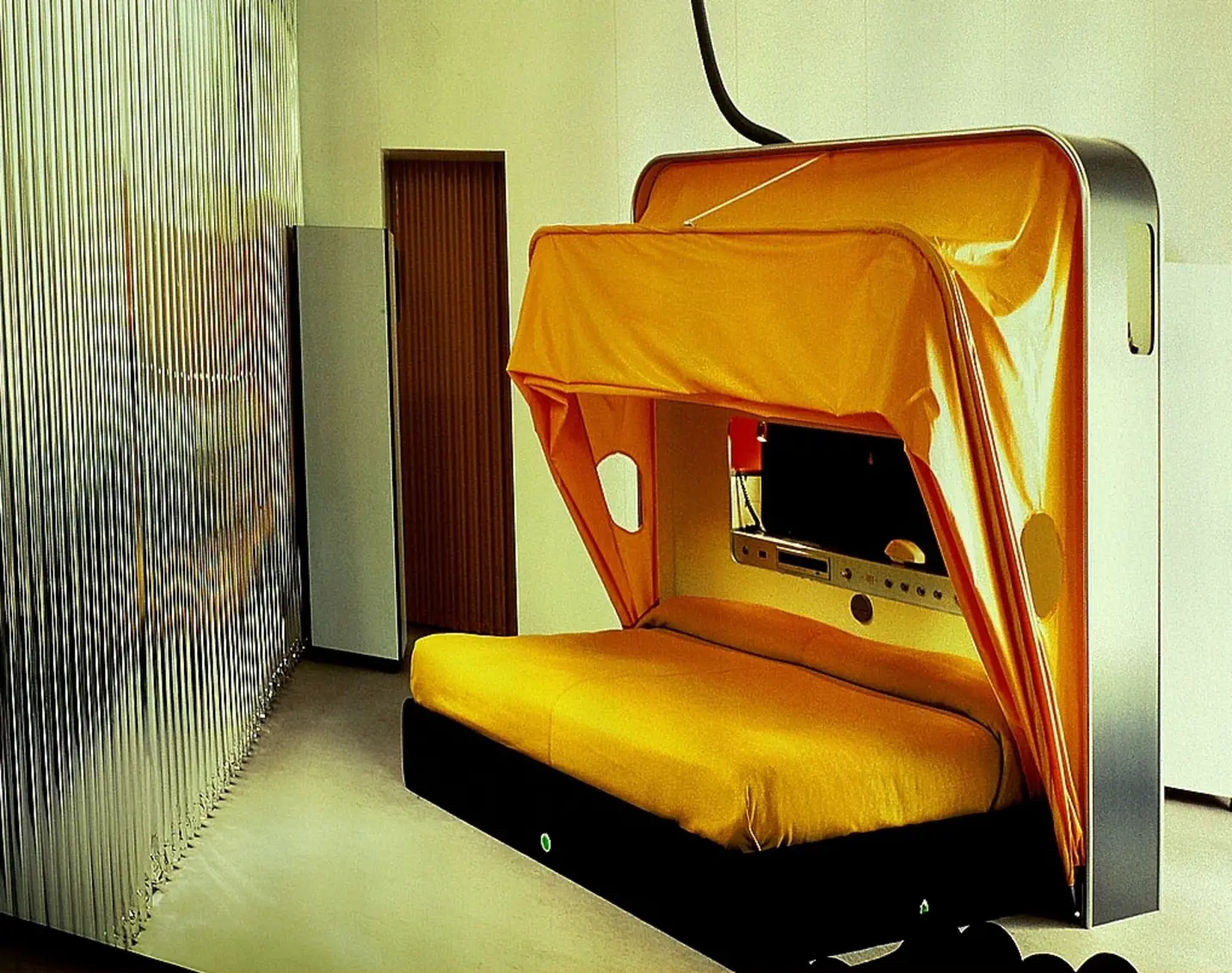

Colombo’s vision extended far beyond the form of individual products—he dreamed of a “modular life,” where all daily needs could be contained within a single system. Designs such as the Total Furnishing Unit and the Cabriolet Bed embody this ambition, resembling Swiss Army Knife versions of living space.

In 2022, the exhibition “Dear Joe Colombo, you taught us the future” was held at Milan Design Week in tribute to him—a gifted soul who left us far too soon.

If Ettore Sottsass was the rebel with his electric palette and surreal forms, then Gae Aulenti was the architect of light, where history was transformed through poetic intuition. Both—in their own distinct ways—rewrote the language of Italian design in the 20th century.

After creating a global sensation with the Valentine typewriter for Olivetti, Sottsass crossed all boundaries by founding the Memphis Group in 1981. This was a manifesto against excessive minimalism and against the coldness of functionalism: “When I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism. It's not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting.”

The Memphis tables, cabinets, and lamps formed a universe of vibrant colors, hybrid materials, and structures that seemed to belong to another planet.

Sottsass paid particular attention to chairs; in his words: “A chair must be a really important object, because my mother always told me to offer my chair to a lady.”

Superstar David Bowie was a quiet yet passionate collector of Memphis works, a true testament to the cross-cultural allure of Sottsass.

“Light is impressionism”, said Gae Aulenti — one of the rare women to stand firm in the male-dominated world of design, was a true creator of emotions. From lamps inspired by astronomy to the transformation of the former Orsay railway station into the renowned Musée d'Orsay in Paris, Aulenti combined mechanics and poetry, memory and future.

Aulenti was truly a storyteller through light, through space, and through bold yet feminine curves.

Gae Aulenti’s Pipistrello lamp (1965), with its bat-like outstretched wings, remains an eternal icon of Italian interior lighting design and has been in continuous production to this day. Italy has long produced designers who are sharp, aesthetic-minded, and unafraid of breaking rules, three qualities that have made Italian design legendary on the global map of beauty.