Jean Nouvel sidesteps the idea of a signature style. Phantom glass, shifting light, and perceptual tricks allow his buildings to change character with place and time, less about instant recognition, more about how architecture quietly alters the way it is felt.

Jean Nouvel sidesteps the idea of a signature style. Phantom glass, shifting light, and perceptual tricks allow his buildings to change character with place and time, less about instant recognition, more about how architecture quietly alters the way it is felt.

January 19, 2026

Jean Nouvel sidesteps the idea of a signature style. Phantom glass, shifting light, and perceptual tricks allow his buildings to change character with place and time, less about instant recognition, more about how architecture quietly alters the way it is felt.

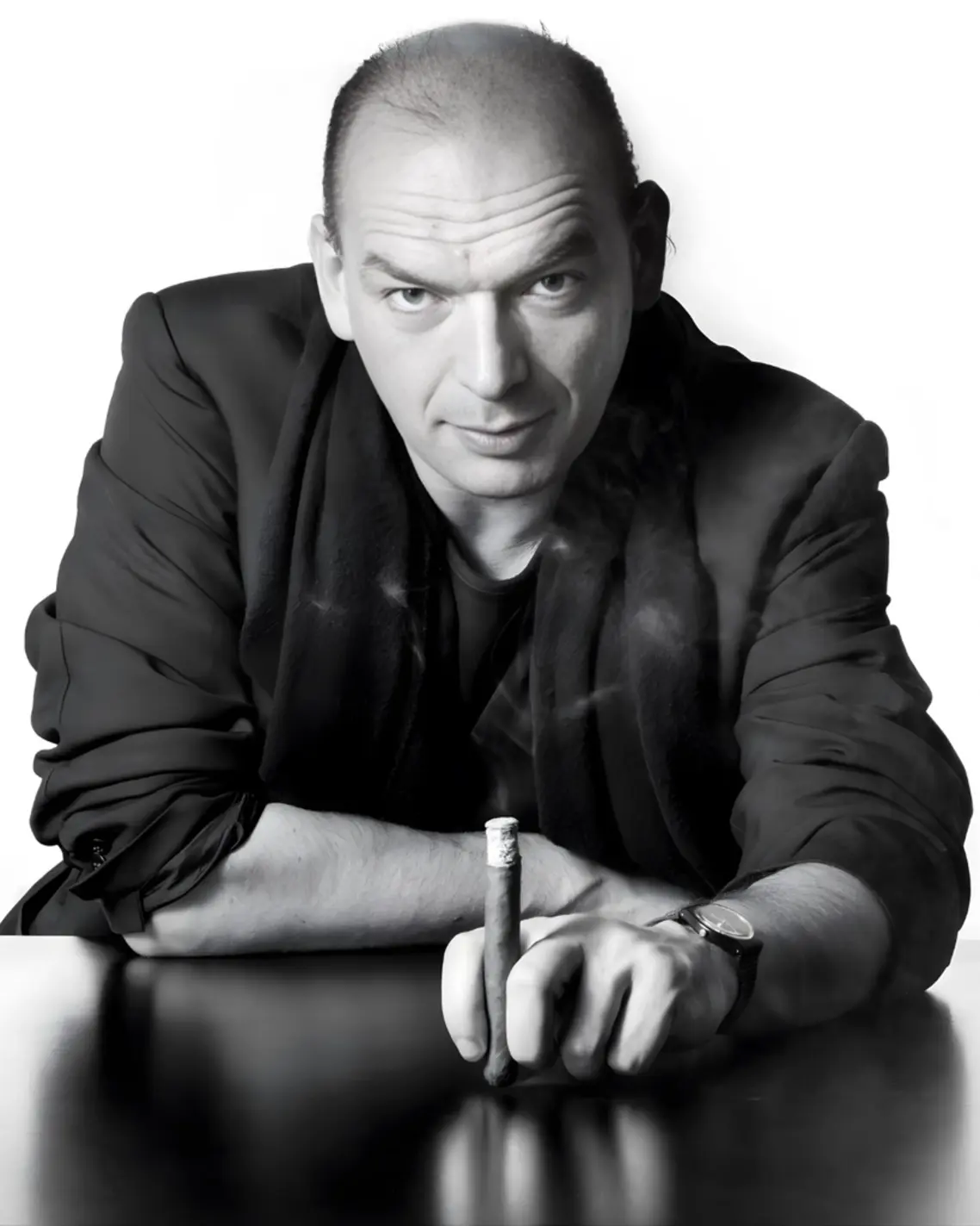

Jean Nouvel tends to arrive like a villain from a French New Wave film: black from head to toe, black-rimmed glasses framing unwavering eyes. One look and one can tell, that is a man who could either sketch a building or dismantle an argument with the same pen. Fiercely emotional and uncompromising, he is legendary for a post-competition meltdown: His unbuilt Bibliothèque nationale de France - a four L-shaped “open-book” towers around a sunken forest, was rejected, causing him to burn all of his models and drawings in a fire of rage.

It captures him perfectly. Nouvel works less like a service provider than a philosopher-director, turning each commission into a thesis on light, narrative, and perception - architecture as something that makes you feel first, and understand later.

When the Pritzker Prize crowned him in 2008, the write-ups kept circling the same paradox: here was a global “starchitect” whose fame came from refusing the one thing the world asks of its stars - a signature style. Unlike the instant niches of his peers: Zaha Hadid’s liquid futurism, Tadao Ando’s meditative minimalism or Renzo Piano’s refined precision, Nouvel lets atmosphere take the reign. The Pritzker materials framed him not as a brand, but as an “experimental philosopher of construction.” His core tenet, and his central provocation, is the doctrine of radical contextualism. He declares no personal style. Each building must be a unique, unrepeatable answer to its specific site, program, and cultural moment. This is the anti-logo in a world that loves logos; a direct rejection of the ego-driven “object-building.” It is a risky, intellectual dare to clients: don’t hire me for a ‘Nouvel look’, hire me to invent something that has never existed before, just for this place.

Of course, this unique approach means no Nouvel's buildings are the same.

His breakthrough, the Institut du Monde Arabe, announced Jean Nouvel’s intentions with surgical clarity. Rather than reaching for a nostalgic dome or ornamental pastiche, he designed a south façade that behaves like a camera mid–rack focus: a field of photo-sensitive metal diaphragms inspired by mashrabiya patterns, opening and closing to regulate light as if the building itself were squinting at the sun. In architectural terms, it behaves like a high-tech brise-soleil, modulating glare and heat while creating a constantly shifting screen of shadow.

The brilliance lies in the double reading. From afar, the façade presents an abstract lattice that belongs to modern Paris. Up close, it evokes a lineage of Arab screens that mediate privacy, temperature, and luminous beauty. Culture appears here as an operational principle, embedded into performance rather than applied as ornament. The message was pointed: architecture for a specific culture could look radically forward, not backward, and still remain deeply respectful. It was cultural reference without mimicry - Arab geometry translated through advanced mechanics.

In Minneapolis, Nouvel changed dialect entirely. The Guthrie Theater appears as a midnight-blue monolith, austere and cinematic, punctured by a searing yellow cantilever known as the “Endless Bridge.” Thrusting nearly 180 feet toward the Mississippi, it places visitors in a position that feels part observation deck, part stage set. The gesture is both thrilling and faintly unnerving - an architectural dare that turns the industrial riverfront into active scenery. Nouvel is not decorating the city here; he is choreographing how bodies, views, and nerves engage with it.

Here the contextual move is psychological as much as visual. The site’s industrial legacy, the river’s breadth, the city’s winter light - these factors become choreography. Nouvel treats circulation as a sequence of shots: narrow passages opening into sudden vistas, darkness yielding to glare, enclosure yielding to exposure. The building functions like a theater before the theater - a prelude that prepares the body to experience drama.

Then comes the Louvre Abu Dhabi, where Nouvel abandons the idea of a single object altogether. What emerges instead is a “museum city” sheltered beneath a colossal dome that converts sunlight into drifting constellations - the celebrated “rain of light.” The dome’s poetry is underwritten by obsessive precision: 180 meters in diameter, eight layered lattices, thousands of star-shaped apertures. Its magic was refined through full-scale mock-ups, tested physically rather than simulated abstractly.

Across these projects, Nouvel’s architecture behaves like a high-stakes performance. Complexity is embraced, illusion is cultivated, and difficulty is occasionally intentional. That intensity turns confrontational in the Philharmonie de Paris. Its massing reads as a deliberate refusal of classical concert-hall symmetry, wrapped in metallic textures that catch a constantly changing Parisian sky. Where many cultural institutions seek polite monumentality, Nouvel pursues a living surface, one that appears to ripple, fracture, and recompose as viewers move. Public debate follows, as it often does with Nouvel: the building’s role expands beyond sheltering a program into provoking a civic argument about what contemporary culture should look like.

That same obsession with perception surfaces again in Manhattan at 100 11th Avenue. The condominium’s façade, composed of roughly 1,600 windows in dozens of sizes and angles, behaves like a fractured mirror. There is no single reflection, no stable image, only a constantly shifting collage of river, traffic, sky, and city. The building resists iconic fixity; it exists to remix its surroundings. Context stops being scenery and becomes content.

In Paris, Nouvel pushes illusion toward near-disappearance. At the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, layers of ultra-clear glass dissolve boundaries between architecture and garden until the building reads like a phantom.

At the Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, the façade shifts again, from mirror to landscape. Living walls, planted surfaces, and meandering paths replace the didactic museum front. Movement becomes wandering rather than marching; encounter replaces instruction. The building reads as a cultural institution that chooses atmosphere and immersion over an authoritative face. Visitors absorb the museum as a sequence of sensory episodes: vegetation, shadow, textured surfaces, partial views, sudden openings. The city receives a museum that behaves like a walk, with all the ambiguity that a walk implies.

And so we return to the black shirt: a kind of deliberate camouflage, a personal constant worn by an architect who distrusts constants in form. Jean Nouvel leaves no trademark silhouette behind, only a persistent belief that architecture reaches its highest charge when the site, the culture, and the moment step forward as the true protagonists.