Paris was still buttoned in wartime khaki when Christian Dior arrived, tossing fabric like confetti, turning women from soldiers of austerity into generals of silk, commanding a new feminine empire

Paris was still buttoned in wartime khaki when Christian Dior arrived, tossing fabric like confetti, turning women from soldiers of austerity into generals of silk, commanding a new feminine empire

November 29, 2025

Once upon a time, in the seaside town of Granville, Normandy, a boy was born who would one day convince the world that women should dress like flowers instead of soldiers. This boy, Christian Dior, came into the world on January 21, 1905, the second of five children in a comfortably wealthy family. His father made his fortune in fertilizers, hardly glamorous, but profitable enough to finance a Parisian home when Christian was five.

From an early age, Dior was enchanted by all things beautiful: ornate blooms, glittering trinkets, and the soft rustle of silk. While other children may have been collecting marbles, young Christian was sketching and soaking in the art of Paris. He dreamed of painting, not power; watercolors, not war. The Parisian art scene in the 1920s was his playground, and he rubbed elbows with artistic luminaries like Jean Cocteau and Salvador Dalí. His father, however, had grander plans: politics. Dutifully, Dior enrolled in political science, but it was a short-lived working By 1928, he had swapped statecraft for canvas, opening an art gallery with his friend Jacques Bonjean, hosting works by Picasso, Braque, and Matisse.

But the glittering days were short-lived. The Great Depression of 1929, paired with devastating family losses and the collapse of his father’s business, turned Dior’s life from silk to sackcloth almost overnight. He went from gallery owner to penniless wanderer, carrying sketches instead of suitcases.

In his memoir, Dior later admitted to turning to tarot readings during these dark years, one prophecy in particular stayed with him: “You will suffer poverty for a time, but women will desire you all your life.” At the time, it sounded absurd. Yet, the “desire” would come. Not for Dior himself, but for the vision of women he was destined to create.

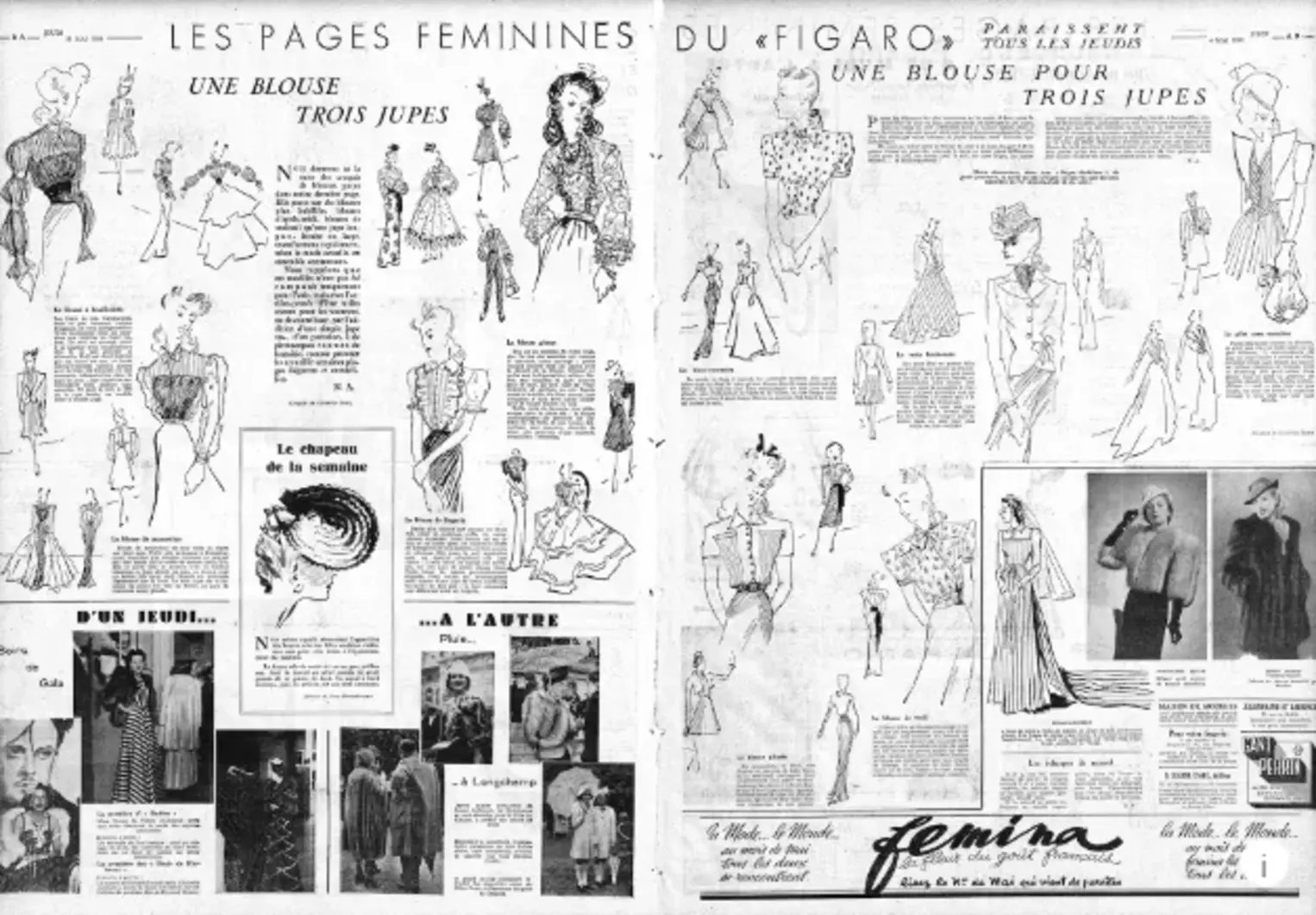

In the mid-1930s, Christian Dior’s artistic path began to merge with fashion. He sold his sketches to prestigious couture houses such as Jean Patou, Balenciaga, and Schiaparelli. He also contributed illustrations to Le Figaro and Jardin des Modes.

In 1938, Robert Piguet offered Dior a coveted place in his house, where Dior crafted soft, romantic dresses that carried the seeds of his future signature style. Yet history intervened. World War II called him to military service from 1939 to 1940. Returning to a Paris under occupation, Dior joined Lucien Lelong’s atelier alongside Pierre Balmain.

Here, he mastered haute couture’s technical precision under extreme constraints. Fabric was scarce, clients were often wives of German officers or members of French high society, and every garment had to balance resourcefulness with beauty. Dior also witnessed the transformation of women’s wardrobes: gone were the opulent layers of pre-war Paris, replaced by utilitarian suits, boxy shoulders, and cropped skirts designed for women’s wardrobes bore the imprint of uniforms. It was a look shaped by resilience, admirable, yet far from the dreamy, flower-like silhouettes Dior envisioned. The contrast would fuel the revolution he was soon to ignite.

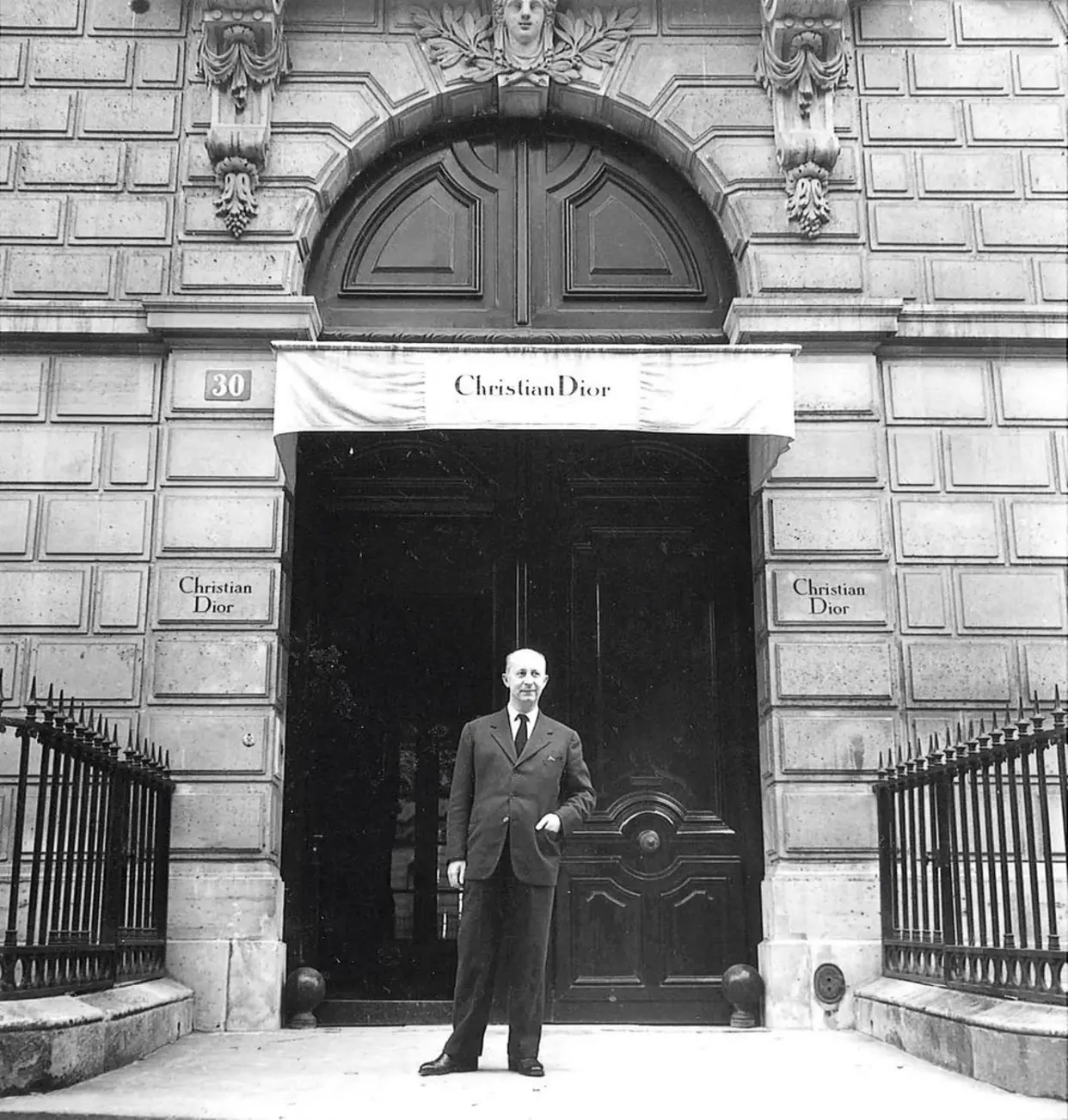

On December 16, 1946, with the backing of textile magnate Marcel Boussac, Dior opened his couture house at 30 Avenue Montaigne, Paris. The space hummed with anticipation: three ateliers, 85 staff, and the scent of a revolution in the making.

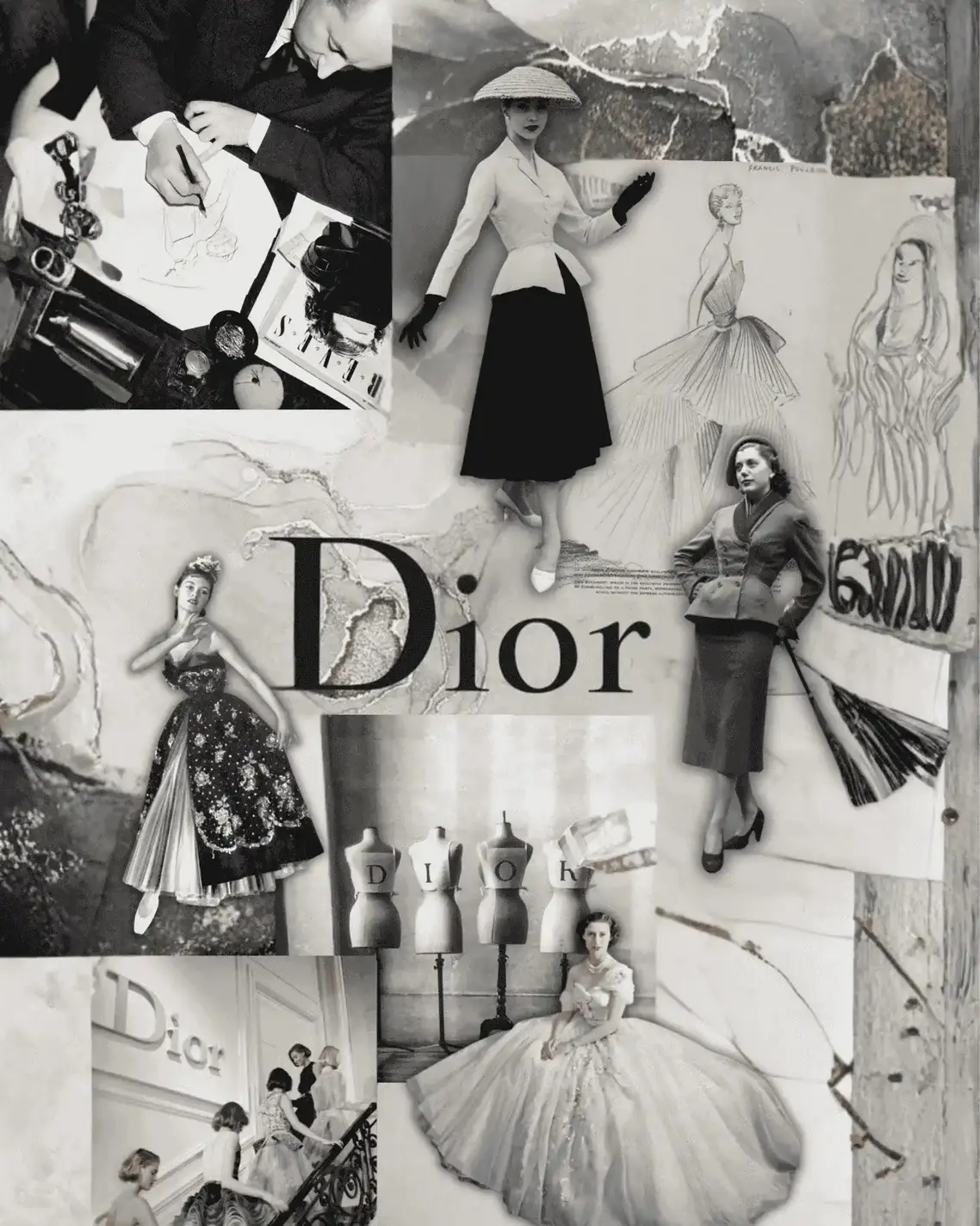

Then came February 12, 1947. In the hushed salons of Avenue Montaigne, Dior unveiled his first collection: 90 looks, split into two lines - Corolle (like the petals of a flower) and En Huit (suggesting the number eight, an ode to the wasp waist and flared hip). It was Carmel Snow, editor of Harper’s Bazaar, who christened it “The New Look” when she exclaimed backstage, “It’s quite a revolution, dear Christian! Your dresses have such a new look.”

The “New Look” was a love letter to femininity after years of wartime masculinity. Out went the squared shoulders, military cuts, and fabric-starved skirts. In came an hourglass dream: rounded shoulders, a soft full bust, a wasp waist you could almost cup in two hands, and skirts so voluminous they seemed to blossom from the hips. Dior’s designs were architectural yet romantic, structured yet flowing.

To women who had spent years in uniforms, factory overalls, and utility frocks, the New Look was intoxicating. It was about reclaiming beauty, grace, and personal pleasure. And, though some critics accused him of turning back the clock on women’s liberation, Dior insisted he was moving it forward. “I wanted my dresses to be constructed, molded on the curves of the female body whose contours they would stylise,” he wrote. “I wanted to return to the forgotten idea of the beautiful clothes, to bring back the luxurious fabrics, the full skirts, and the elegance that had disappeared.”

Central to that debut was the Bar Suit, anchored by the now-legendary Bar Jacket. Dior named it after the bar at the Plaza Athénée in Paris, a nod to the elegance of its clientele. Its design was pure sculpture: sharply tailored shoulders, a cinched waist so precise it could be measured in hand spans, and a peplum that flared over padded hips.

Made from structured wool or silk shantung, it took 150 to 500 hours to complete, with multiple fittings to ensure it molded flawlessly to the wearer. Pierre Cardin engineered its internal structure with layers of padding, cotton underlining, and strategic stitching, so the jacket would hold its shape yet feel light. This was Dior’s philosophy in fabric: that a woman’s form was something to be celebrated, framed, and revered, not disguised in the flat lines of wartime utility wear.

The Bar Jacket became a recurring character in Dior’s collections, reappearing in countless variations until his death in 1957. It stood for elegance, for architecture as couture, and for the conviction that craftsmanship could create a kind of wearable ideal.

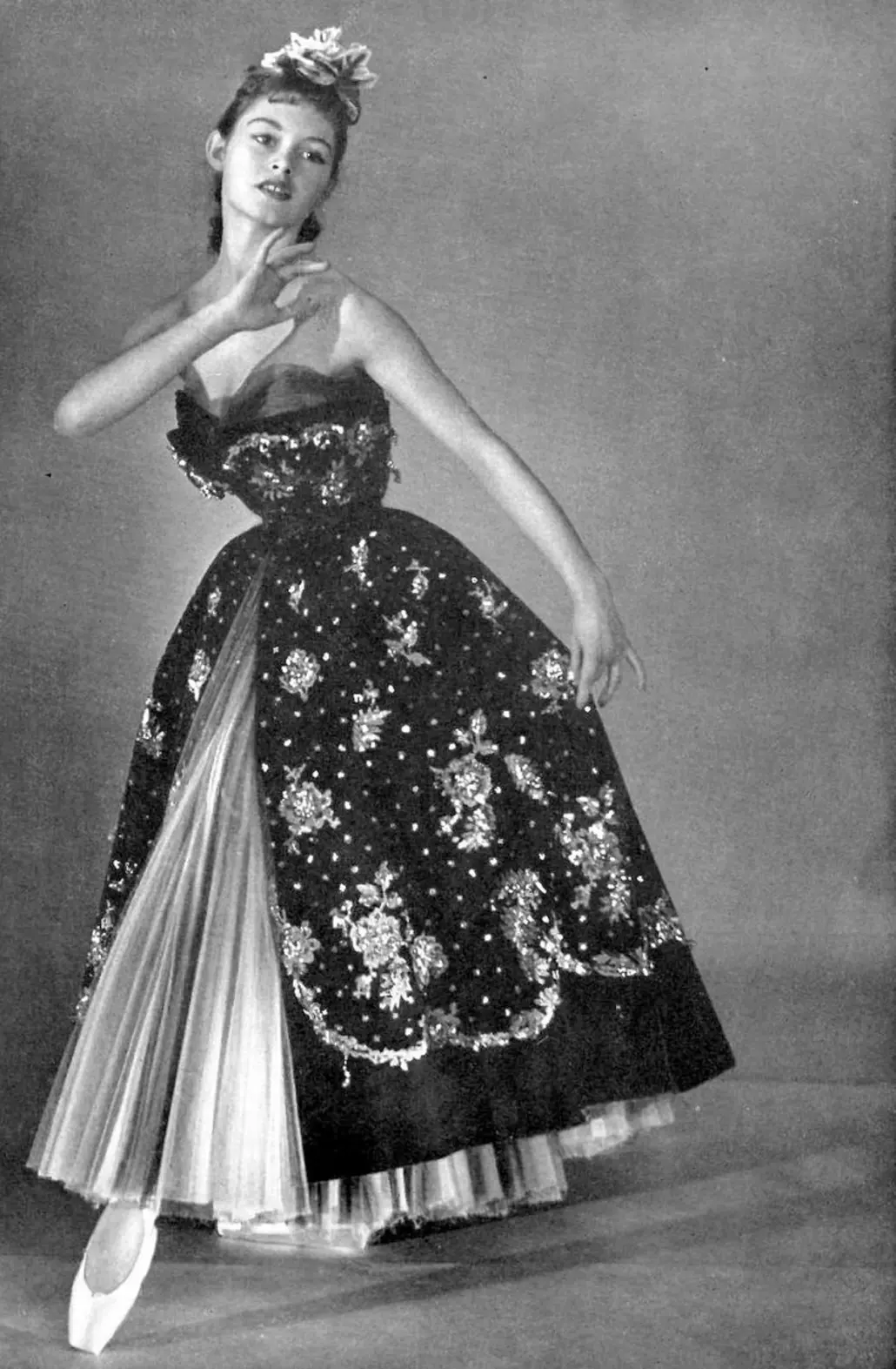

If the Bar Jacket was Dior’s architectural manifesto, La Cigale was his cathedral. Introduced in the Fall/Winter 1952 “Profile Line” collection, the dress was made from heavy grey moiré silk ottoman: a shimmering, textured fabric that held its shape like pliant metal. The skirt was cantilevered at the hips, creating a posture that recalled the grandeur of 17th-century Spanish court portraits.

Its construction was as intricate as any building: molded bodice, strategic volume at the hips, stiff petticoats, boned corsetry, and multiple seams shaping the skirt into a precise curve. The result was a silhouette both regal and otherworldly, a continuation of Dior’s belief that clothing could shape a woman’s bearing as much as her appearance.

Fashion critics hailed La Cigale as a masterpiece. But beyond its technical brilliance, it was another expression of Dior’s aesthetic - clothing as both art and frame, enhancing the natural beauty of the wearer while giving her a new, almost theatrical sense of self.

The extravagance of the New Look drew fire from critics. In war-torn Britain, the “Little Below the Knee Club” protested its long skirts as wasteful. American pragmatists argued it would undo women’s wartime gains by pushing them back into delicate domesticity. Yet even the protests played into Dior’s hands; controversy only heightened the allure.

The truth was, the New Look was not about returning to fragility. It was about reclaiming choice. For years, women had dressed in the same utilitarian silhouettes dictated by rationing and necessity. Dior’s designs gave them permission, and indeed, encouragement: to embrace beauty for its own sake. This was not the uniform of the female worker or soldier; it was the regalia of the woman as she wished to be seen. Feminism, Dior seemed to say, was not only about trousers and factories; it was also about silk, curves, and the joy of dressing for oneself.

Dior exploded across continents with the help of three powerful forces: royalty, Hollywood, and the press. Princess Margaret became one of Dior’s most ardent admirers, wearing his creations at public events and inviting him for private showings at the French Embassy in London. Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, and other royals followed suit. Meanwhile, in Hollywood, Marlene Dietrich famously told filmmakers, “No Dior, no Dietrich,” ensuring his designs were immortalized on screen. Olivia de Havilland, Rita Hayworth, and later Marilyn Monroe brought the Dior desgin to red carpets and silver screens, embedding it in the dreams of millions.

Fashion editors, from Vogue to Harper’s Bazaar, lavished Dior with coverage. Photographs of the Bar Suit and sweeping gowns were splashed across glossy pages, turning the New Look into a global aspiration. Even in cities still recovering from wartime rubble, women began to save for the chance to own just one piece of Dior’s world.

The genius of the Christtian Dior's desgin lay not only in its beauty but in its timing. Postwar women were tired of surviving - they wanted to live. Dior’s designs were a rejection of scarcity and an embrace of abundance of fabric, of form, of femininity. He took the flower that had been crushed under the boot of war and replanted it in the center of the fashion world.

To call the New Look a mere trend would be like calling Versailles a house. It was an architectural reconstruction of femininity itself: women should be dressed as women, in ways that honor their curves, their grace, and their joy in beauty. Each design was connected by the same ideological thread: The New Look was the spark, the Bar Jacket its foundation, La Cigale its sculptural peak.

His own words capture the heart of it: “In December 1946, as a result of the war and uniforms, women still looked and dressed like Amazons. But I designed clothes for flower-like women.” These flowers, however, were not fragile. They were rooted, unapologetic, and ready to bloom in the spotlight of a world learning to love beauty again.

By the late 1940s, Dior’s house accounted for 75% of France’s fashion exports and 5% of the country’s total exports. He revived Paris as the undisputed capital of fashion and set a standard so influential that decades later, his signature shapes still inspire designers worldwide.

When Dior died suddenly in 1957, he left behind not only a thriving house but an aesthetic language - one that says, in every peplum flare and blossoming skirt, that beauty is not frivolous. It is a form of resistance, a reclamation of identity, and, in Dior’s hands, a reminder that after the harshest winters, the flowers always return.