While Gaudí laid the philosophical groundwork for organic architecture, Zaha Hadid - the "Queen of the Curve", was the one who used modern technology to bring that divine geometry into the 21st century.

While Gaudí laid the philosophical groundwork for organic architecture, Zaha Hadid - the "Queen of the Curve", was the one who used modern technology to bring that divine geometry into the 21st century.

January 28, 2026

While Gaudí laid the philosophical groundwork for organic architecture, Zaha Hadid - the "Queen of the Curve", was the one who used modern technology to bring that divine geometry into the 21st century.

Hadid, an Iraqi-British visionary and the first woman to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize, shared Gaudí's disdain for the "boring" straight line, famously stating: "There are 360 degrees, so why stick to one?"

It would be redundant to say Zaha Hadid pursued uniqueness, because in the world of architecture, just like in cinema or horology, there is little room for monotony or unoriginality. Innovation is not a choice; it is a necessity. And few embody this truth as boldly as Hadid. Her work has reshaped the way we think about design itself, earning her the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize - the highest award in architecture, awarded only once in a lifetime. This recognition solidified her place among the legends.

Zaha Hadid did not merely design buildings. She challenged the very idea of them. Why should skyscrapers always stretch upwards in rigid lines? Why not reimagine them with flowing curves, organic forms, and foundations that embrace the earth rather than dominate it? This radical mindset was already evident in some of her early iconic projects, such as the Vitra Fire Station in Weilam Rhein, Germany (1993), the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, USA (1998), and the Hoenheim-North Terminus in Strasbourg, France (2001). Each structure was not just a building; it was a concept brought to life, sculpted with precision and powered by imagination.

Hadid’s groundbreaking approach became even more pronounced in her later projects: the Bergisel Ski Jump in Innsbruck, Austria (2002), the Ordrupgaard Museum extension in Copenhagen, Denmark (2005), the futuristic Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg, Germany (2005), the Nordkettenbahn funicular stations (2005), and the BMW Central Building in Leipzig (2005). In each of these, Hadid abandoned traditional architectural norms, unleashing a liberated design language that gave birth to what we now call Deconstructivism.

Deconstructivist architecture - born as a reaction to the predictability of Postmodernism - is chaotic, asymmetrical, and deliberately destabilizing. It reimagines space through a lens of movement, distortion, and unexpected harmony. Zaha Hadid was one of the first to truly master this language. Her structures often appear on the verge of motion - like frozen waves, cracked landscapes, or shards of glass in mid-fall. They challenge our perceptions, and that is exactly the point.

Yet despite their visual complexity, Hadid’s buildings never lack purpose or meaning. There is a reason behind every unexpected angle and every sweeping curve. She did not design for shock, she designed to express freedom. Structural freedom. Creative freedom. Human freedom.

No architecture or design student can graduate without knowing Zaha Hadid. To ignore her in this field is like studying finance and missing the Rothschilds. More than a name, she was a revolution, breaking open a new dimension of architectural thinking that others could only follow or admire.

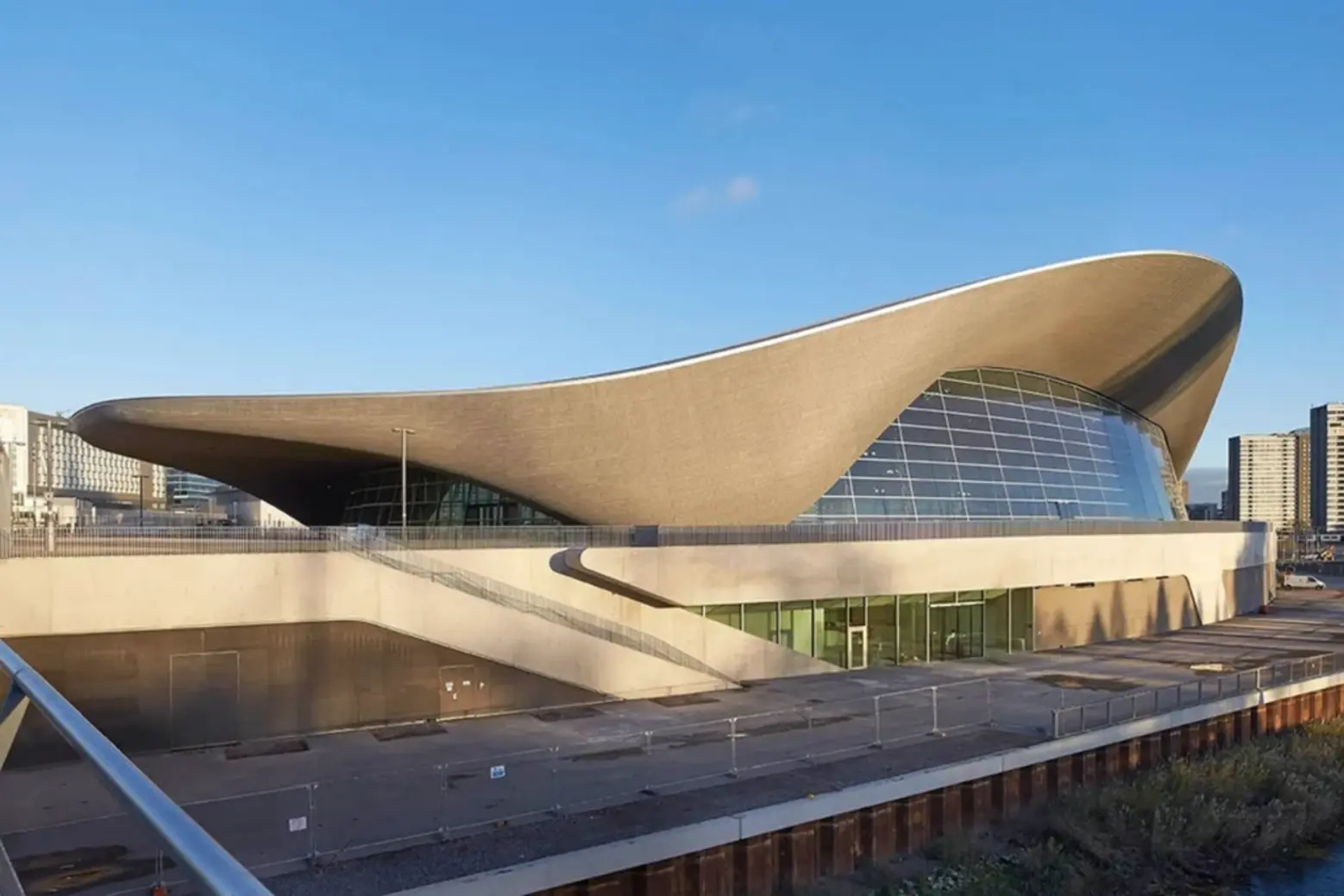

While male architects are often stunned by scale and sharp lines, Hadid offered something different. Her designs did not shout, they flowed. Sensual, fluid, and digitally visionary, they embodied elegance without sacrificing innovation. Her London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympics, with its wave-like roof, stands as a perfect example, a sports venue that feels more like a sculpture in motion.

Yet her journey was not without setbacks. Dismissed early on as a “paper architect,” many of her radical designs stayed on paper. That changed in 1994 with her first built project, the Vitra Fire Station. By 2004, she made history as the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize. Hadid did not just design buildings; she reshaped the future of architecture itself.

Born on October 31, 1950, and passing away unexpectedly on March 31, 2016, Zaha Hadid was a woman shaped not just by education and ambition, but also by heritage. Of Iraqi origin and later a British citizen, Hadid was raised in a prominent upper-class Muslim family. Her father was a well-known politician and industrialist, while her mother came from a wealthy background. These roots cultivated in her a boldness of thought and independence of vision that would later fuel her revolutionary designs.

Before entering the world of architecture, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut - an intellectual foundation that would deeply influence the geometric complexity of her later work. She then trained at the prestigious Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, where she studied under and later assisted, the renowned Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, another Pritzker laureate. Whose experimental philosophies left a lasting impact on her.

In 1979, Hadid launched her own design firm, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), in London. Despite initial challenges in gaining commissions, her firm would eventually become one of the most sought-after architecture practices in the world. At the time of her death, she was working on monumental projects including the 20,000-seat Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympics, which has since become a model for sustainable, post-event urban architecture.

Beyond architecture, Hadid was also a prolific interior and industrial designer. She created spaces such as the Mind Zone for the Millennium Dome in London, a bold and futuristic installation that once again fused form and function in ways few had imagined possible. Her influence spread to furniture, fashion, and even sneaker design, collaborating with brands like Lacoste and Adidas, and always pushing the boundaries between disciplines.

Even after her death, Zaha Hadid Architects continues her legacy, led by Patrik Schumacher, maintaining the firm’s dedication to parametric design and urban innovation. Recent projects like the King Abdullah Financial District Metro Station in Riyadh and the BEEAH Headquarters in Sharjah show that Hadid’s signature vision, bold, daring, and deeply humane, remains alive and evolving.

Zaha Hadid’s vision extended far beyond blueprints and building permits. Her aesthetic sensibility and taste for the avant-garde found a natural synergy with the fashion world, a relationship that reflected the increasing intersection of design disciplines in the 21st century.

In 2009, Hadid collaborated with Lacoste to create a revolutionary pair of boots inspired by her architectural philosophy. The design, featuring sculptural contours and fluid lines, mirrored the dynamic, futuristic structures for which she was renowned. This collaboration was more than just a product drop; it symbolized the beginning of a trend where architectural designers crossed over into the world of fashion, influencing shadows, materials, and the very identity of wearable art.

Another extraordinary partnership was with Chanel. Tasked with designing a traveling exhibition space, Hadid created the Mobile Art Pavilion - an architectural marvel that journeyed from Hong Kong to Tokyo, New York to Paris. The structure was inspired by Chanel’s signature quilted handbag pattern and was conceived as a space of contrast and ambiguity. Interior merged with exterior, artificial light played against natural shadows, and the boundary between man-made and organic forms blurred in unexpected harmony.

Inside, visitors encountered curated artworks from contemporary artists, chosen specifically for each location of the pavilion. The experience was not just visual but immersive, blending spatial movement with interactive technology. It was, as Hadid described it, “architecture as choreography” - a physical and emotional dance through form and light.

Zaha Hadid's entire career was a rebellion against the conventional and a triumph of imagination over limitation. In a profession dominated by men, she carved out space for feminine expression not by conforming, but by excelling. Her buildings are impossible to ignore, neither timid nor decorative, but powerful embodiments of beauty and brainpower.

And even after her passing, her firm continues her legacy. Today, Zaha Hadid Architects remains one of the most prestigious and progressive studios in the world, continuing to explore digital innovation, sustainability, and radical aesthetics.