The most precious things in the world are paper: money and books. And no, you can not change my mind.

The most precious things in the world are paper: money and books. And no, you can not change my mind.

October 16, 2025

The most precious things in the world are paper: money and books. And no, you can not change my mind.

At the pinnacle of the auction world is the Original Print of the U.S. Constitution. This historically monumental document, representing the foundation of a nation, was purchased by collector and billionaire David Rubenstein in November 2022 for an astonishing $43.2 million.

Originating from the Middle Eastern region, the Codex Sassoon, dating back around 1,100 years, was written on parchment and containing all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible. It was sold for $38.1 million to former U.S. Ambassador to Romania Alfred H. Moses, who gifted the manuscript to the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv.

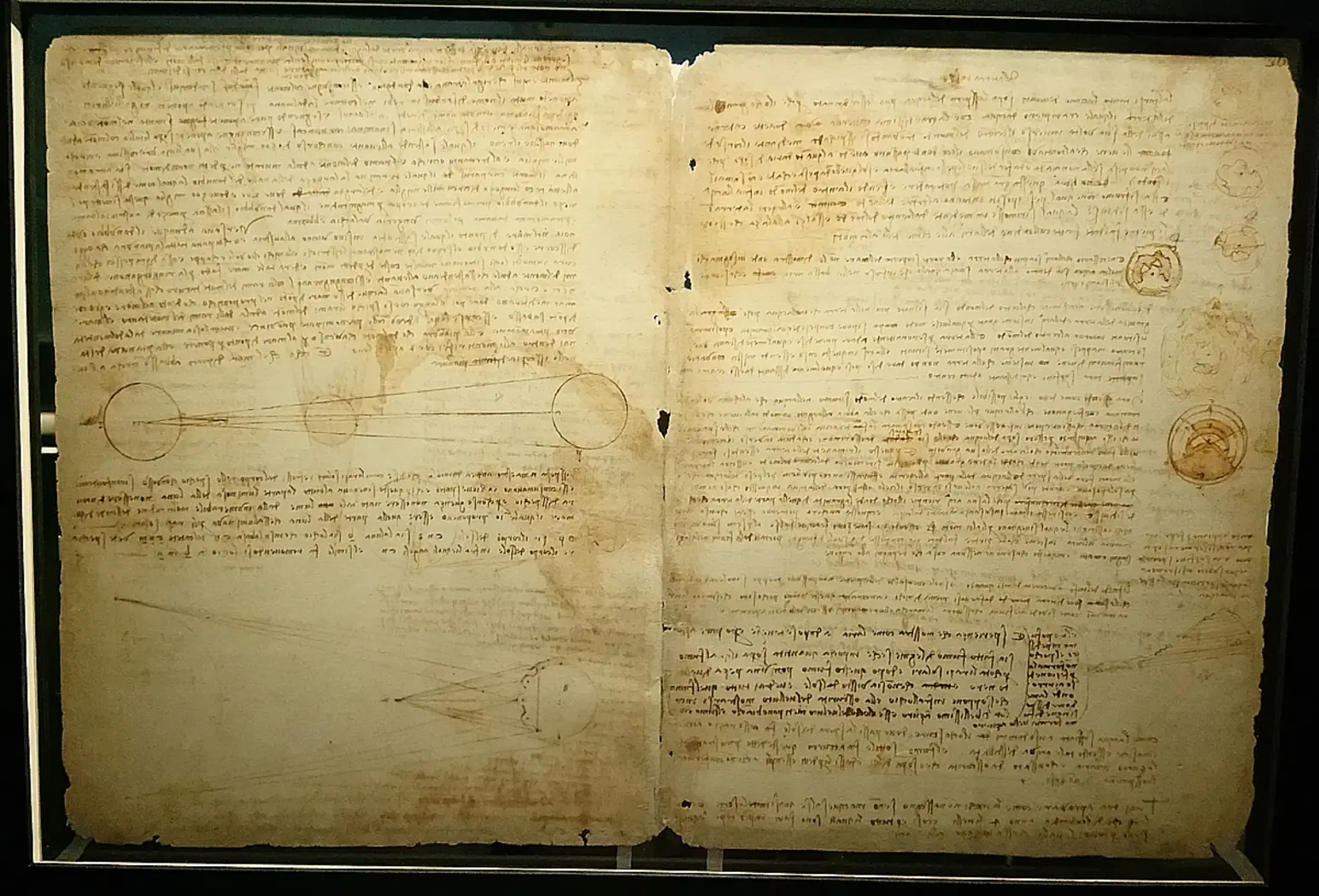

A close contender in both cultural and monetary value is Leonardo da Vinci's Codex Leicester, the notebook filled with the genius's writings, sketches, and diagrams on topics ranging from water flow to the movement of planets. This manuscript was purchased by billionaire Bill Gates for $30.8 million in 1994. Gates later digitized the work and displayed parts of it globally.

The value of a rare book depends greatly on its condition. Hence, the German Gospel and the Irish Books of Kells are preserved in pristine condition. Unfortunately, manuscripts from Iran, India or Turkey, processed through Western trade, do not always get the same treatment.

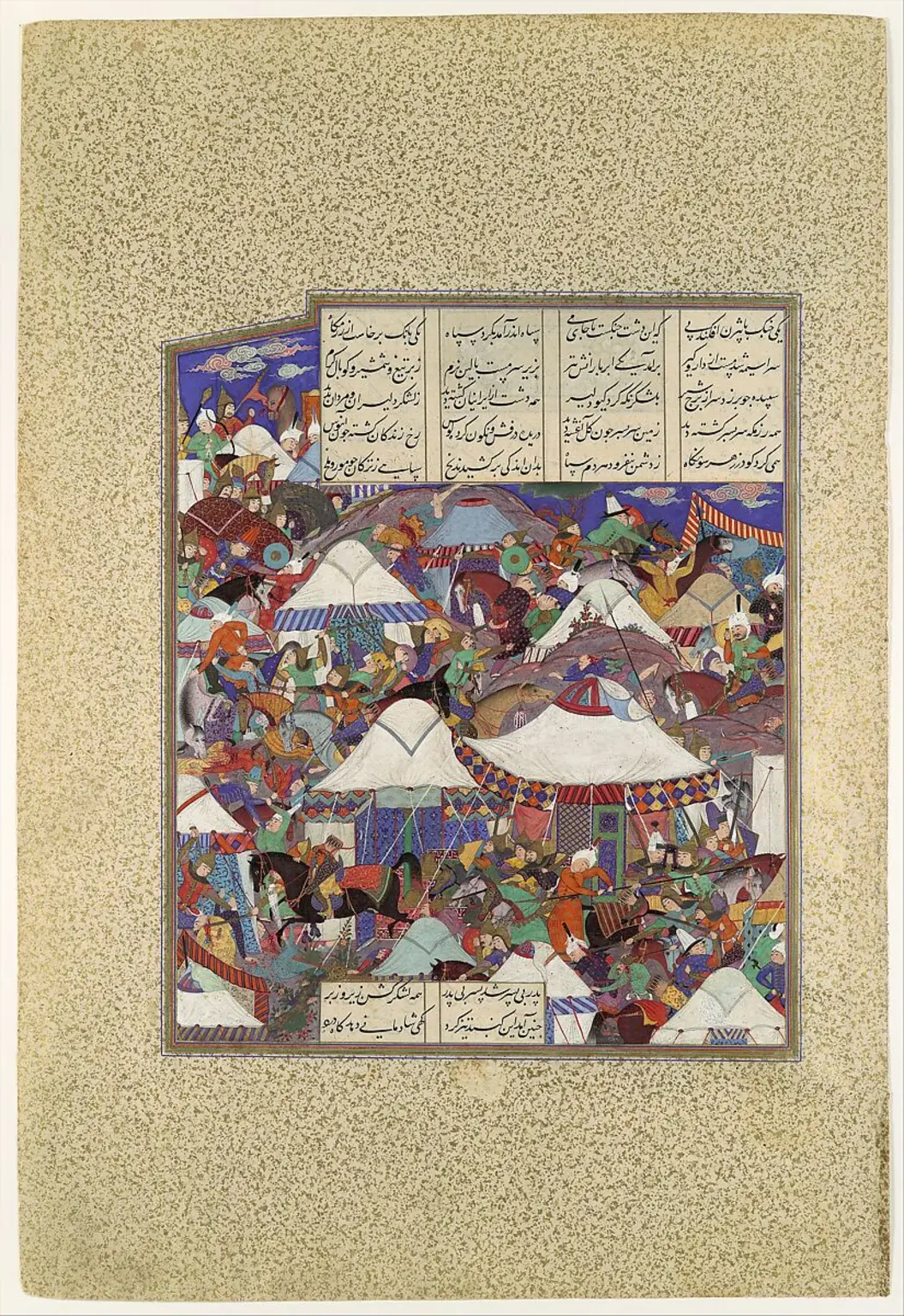

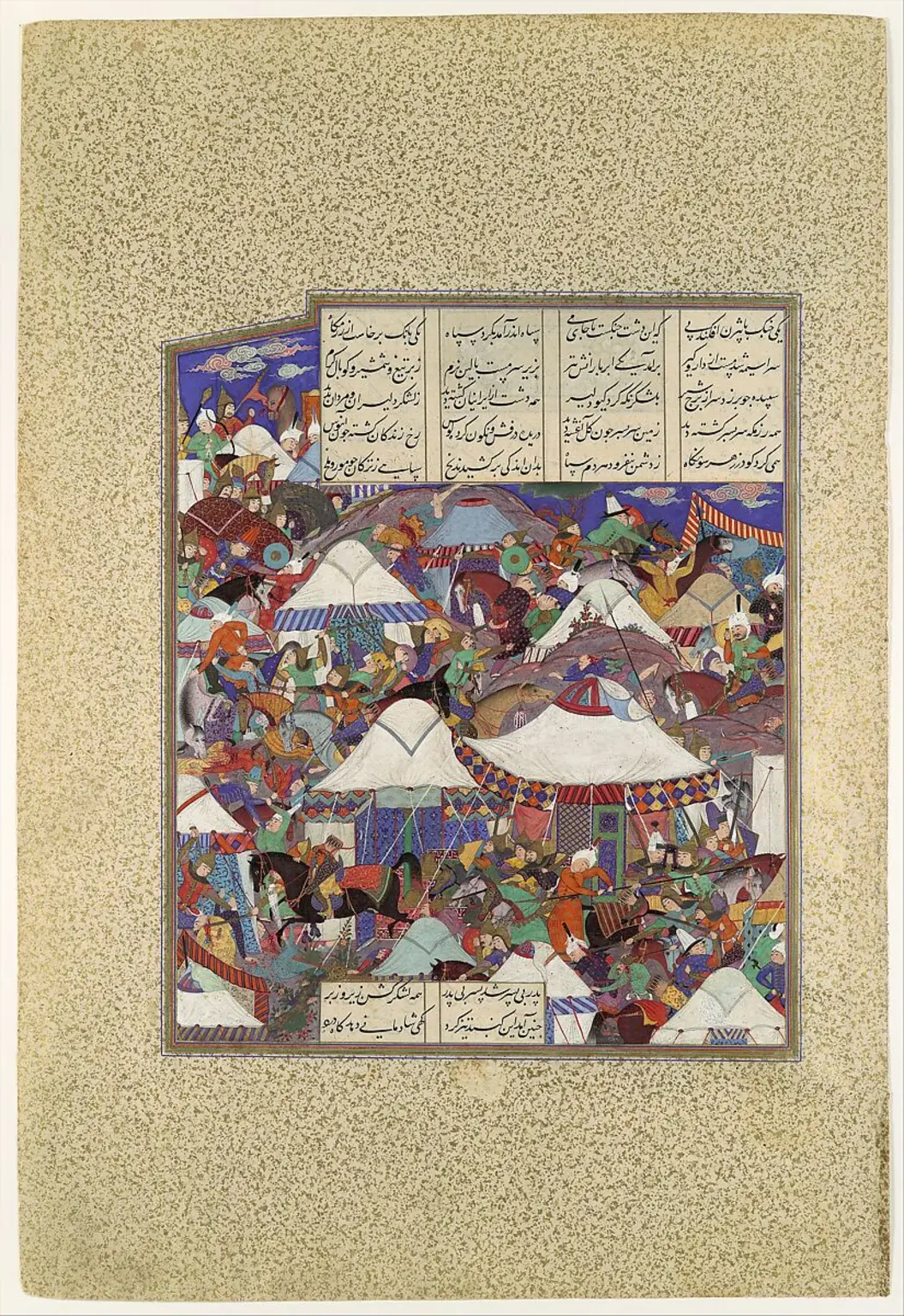

Such a case is the folio of Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. This Persian epic, also known as the "Book of Kings," is a lavishly illustrated work considered a high point in the art of the Persian miniature. The manuscript was commissioned in the 16th century by Shah Ismail and completed under the patronage of his son, Shah Tahmasp. Over a period of two decades, the greatest artists of the royal atelier worked on its 759 pages, which included 258 exquisite miniatures.

Unfortunately, the manuscript was later dismembered, and its pages were sold individually. A single page from this masterpiece, depicting the hero Rustam recovering his horse, sold for a record-breaking $9.4 million at a Sotheby's auction in London in October 26, 2022. The sale highlights not only the book's immense historical and artistic value but also the powerful motivation of some collectors. The buyer was an anonymous Iranian collector living in the West who created a foundation with the explicit purpose of acquiring significant Iranian artworks and eventually returning them to their country of origin. This single sale is a powerful example of how private collecting can be used to preserve cultural heritage for future generations.

Scarcity is only the beginning. The value of a rare book is determined by several key factors that extend far beyond its content. Peter Harrington, a prominent rare book dealer, emphasizes that books are delicate and age over time, much like fine wine, with even exposure to sunlight capable of fading covers and diminishing their value.

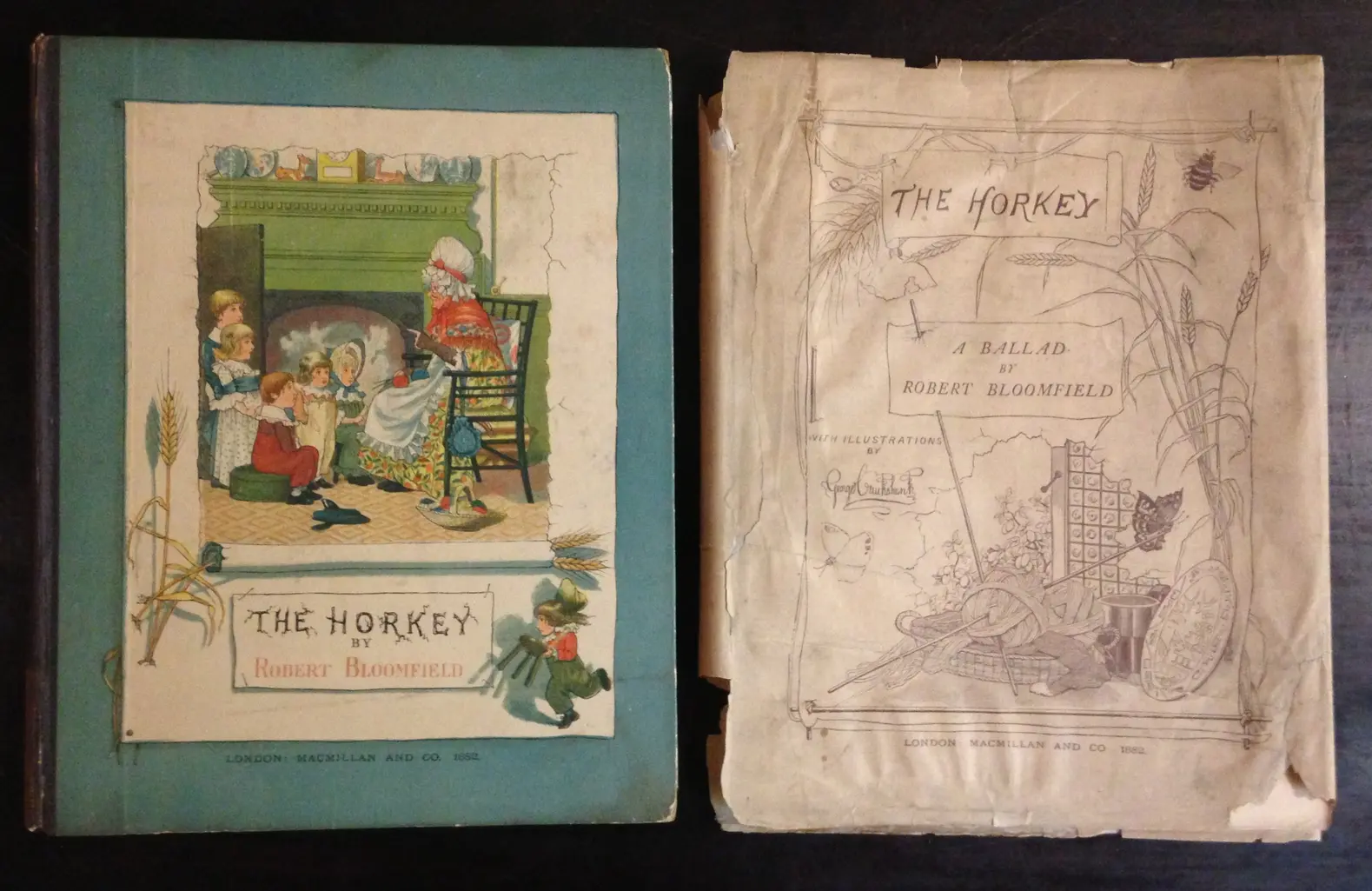

Sometimes, a book's value is more tied to its craftsmanship than its content. The quality of a book’s design, printing, and binding, often created by artists and skilled artisans, can be a more significant factor than the text itself. This is particularly evident in some 17th and 18th-century English books and 20th-century French works, which are prized for their exquisite craftsmanship.

A book's original dust jacket is a critical, and often surprisingly valuable component. Historically, these jackets were often discarded by readers, making intact ones incredibly rare today. Peter Harrington points out that a book with its original dust jacket can be worth an additional £70,000 (about $86,000), highlighting its immense importance to collectors.

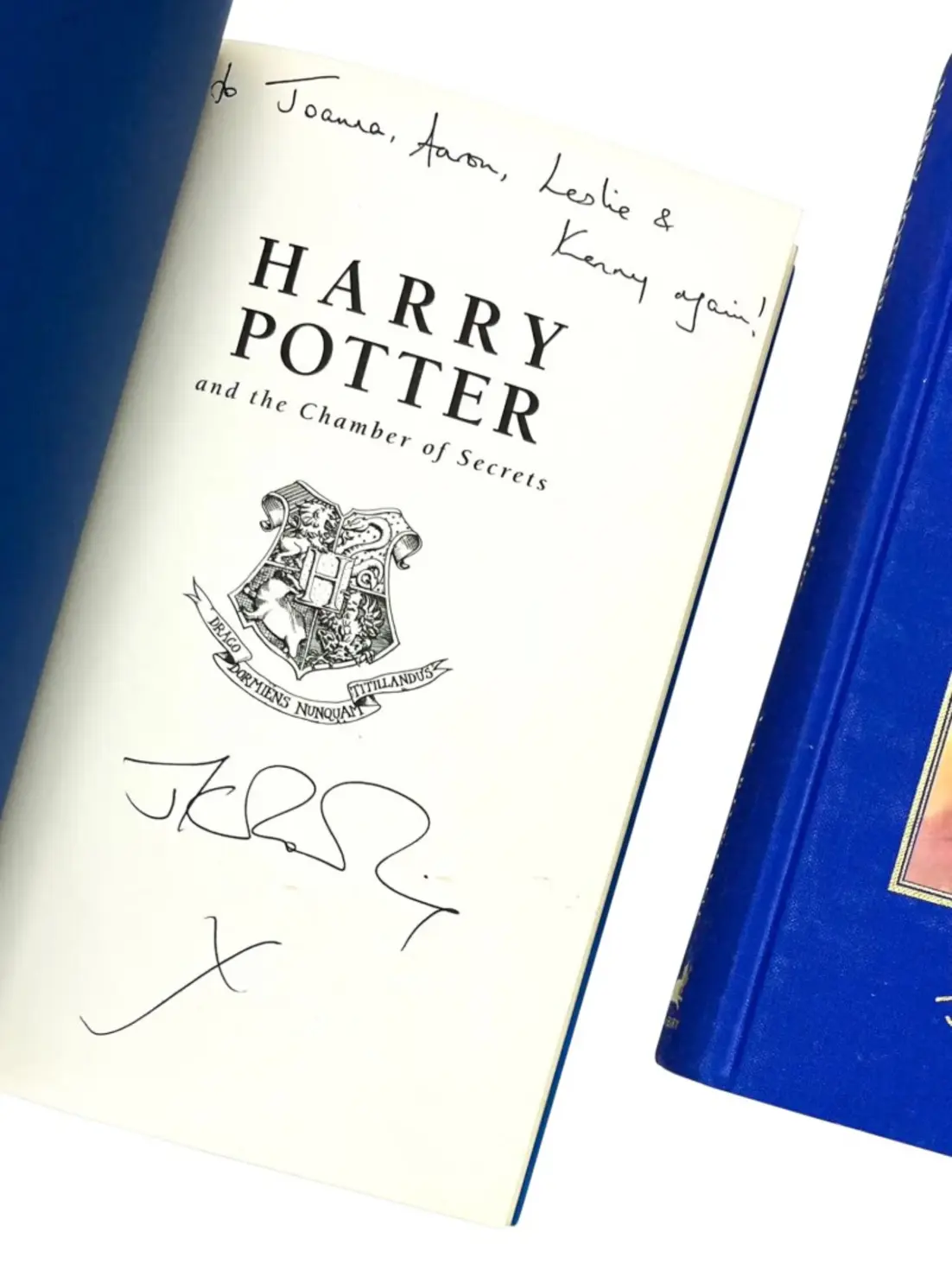

In addition to rarity and condition, several other elements significantly increase a book's value. A signed copy is highly sought after, but the rarity of the signature is key. J.K. Rowling’s reluctance to sign books has made her signed copies extremely valuable, while authors who sign frequently have less valuable signatures. Signatures made at the time of publication are also more desirable than those signed retrospectively.

The context and related events surrounding a book also play a significant role. Cultural events, such as movie adaptations, can spark interest and increase a book's value. The so-called “Hollywood effect” has multiplied the market value of authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling. Similarly, artistic elements like unique illustrations, avant-garde design, or forewords by public figures, function as value accelerators.

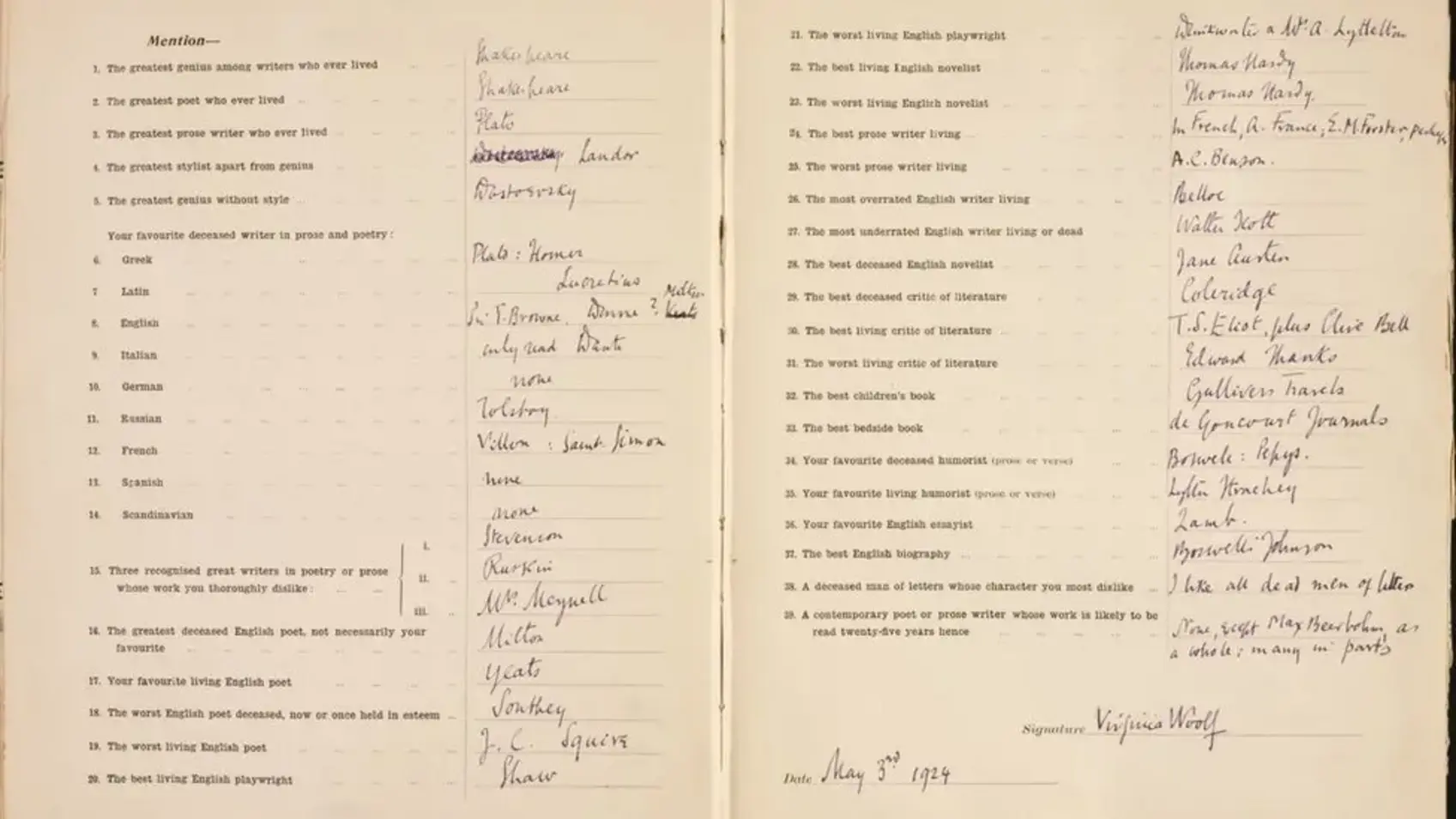

Finally, a book's history of ownership, or provenance, can dramatically boost its price. Books that once belonged to a prominent figure and books that were part of a famous collection are also highly valued.

According to Keith Heddle, investment director at Stanley Gibbons, the rare book market is primarily driven by middle-aged and older individuals, typically between 50 and 60. These individuals often invest in books as a way to convert their income into assets they can pass on to their children, choosing titles that hold personal or educational significance. For these collectors, a rare book is not just a financial asset but a cultural legacy.

A book's value is fundamentally driven by demand, not just its age or rarity. This demand can be influenced by cultural consensus, as seen by The Great Gatsby, or by a renewed interest in authors like Claude McKay or Virginia Woolf.

Interestingly, controversy can also immediately increase a book's price. When a book is "banned" or "canceled," there is often a rush to buy remaining copies, as "banned" doesn't mean "illegal." This phenomenon applies to classics like A Farewell to Arms and Of Mice and Men, making the long list of banned books a unique area for collectors. In 2022, Sotheby's auctioned a special, fireproof copy of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid Tale for $130,000 to raise monetary aid for PEN America to fight censorship and book banning. Before the auction, the 82-year-old author attempted to burn the book with a flamethrower.

Book collecting also helps to preserve work for future generations. Collecting books by authors or in genres that aren't currently popular is a great way to start on a budget, and it can also serve as a unique way to highlight your personality and interests. There's always a chance that a niche collection could become fashionable and increase significantly in value.

The world of book collecting is also becoming more diverse. While the market has historically championed white, straight male authors like Hemingway and Faulkner, interest is now expanding to a wider range of writers. Experts predict that future collectors will increasingly seek out and treasure works by Black women sci-fi authors, LGBTQ+ young adult novelists and Indigenous poets, making diverse collections the new norm rather than the exception.

Ultimately, whether driven by the desire for investment, the preservation of a legacy, or a passion for a particular author or genre, the act of collecting is a testament to the enduring power of the written word.