From Shakespeare’s sicklemen to Jacquemus’s catwalks, from the furrows of Signa to the luxury decks of modern yachts, the Florentine straw hat has endured not as a relic, but as a living hymn to summer.

From Shakespeare’s sicklemen to Jacquemus’s catwalks, from the furrows of Signa to the luxury decks of modern yachts, the Florentine straw hat has endured not as a relic, but as a living hymn to summer.

November 25, 2025

“You sunburned sicklemen, of August wearyCome hither from the furrow, and be merry;Make holyday: your rye straw hats put onAnd these fresh nymphs encounter every oneIn country footing.” — William Shakespeare, The Tempest (Act IV, Scene 1)

There is a moment at the height of summer when the air itself seems golden, when the fields tremble beneath the sun, when the breeze carries the scent of ripening wheat, and when time slows into a soft, honey-colored silence. It is this precise instant that Shakespeare captured, not merely in words, but in spirit, and it is from this moment that the story of the Florentine straw hat, the Cappello di Paglia, begins its timeless dance with sunlight.

Long before the runways of Milan shimmered with light, there were only the fields. Vast, gold-flecked stretches outside Florence, where marzuolo wheat swayed like liquid fire beneath the August sky. The straw was cultivated with intention, planted close together to grow long and slender, then plucked before it matured so that its sap lingered in the stem, softening it like silk spun by the sun itself.

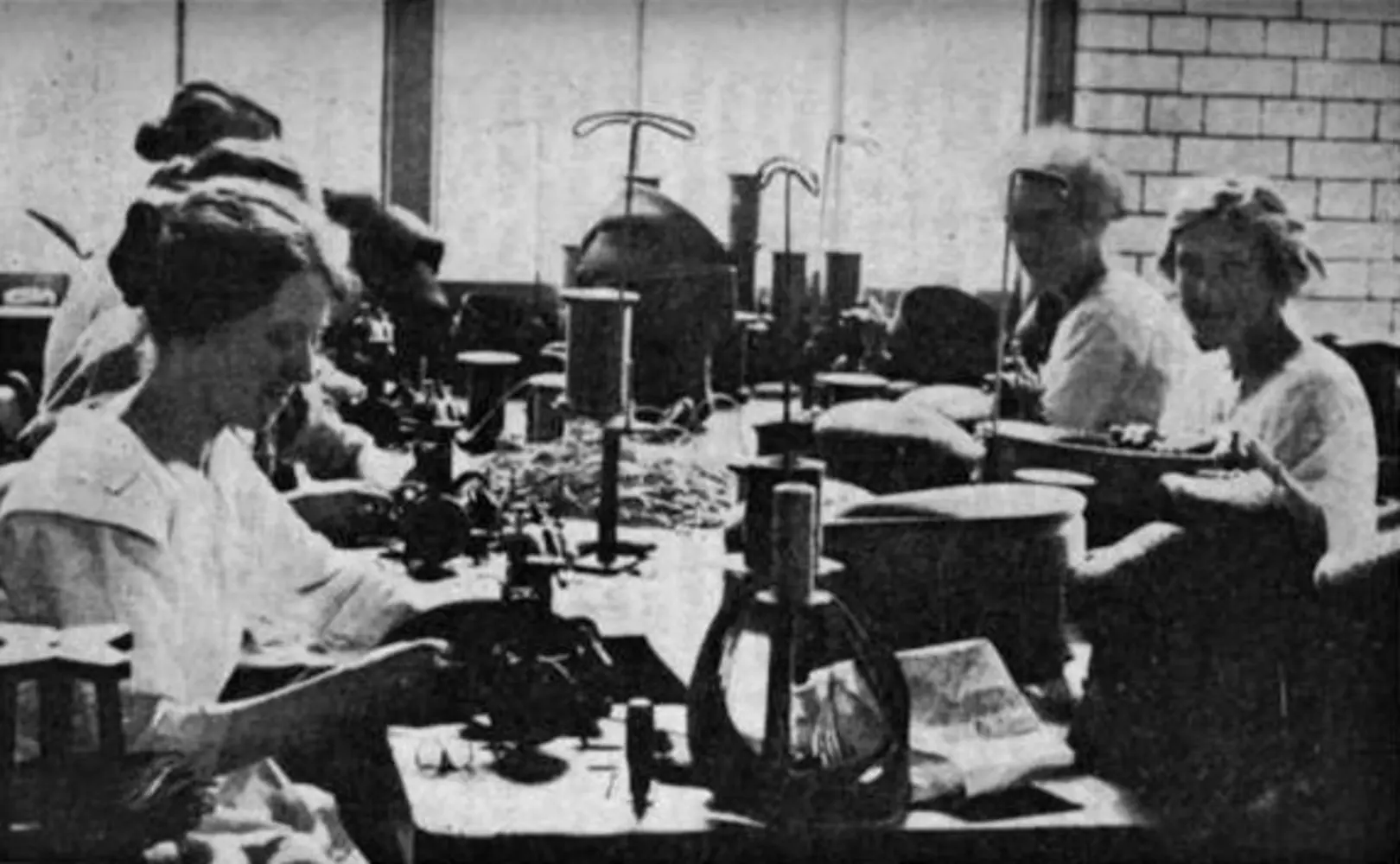

Women, the quiet keepers of this craft- braided the straw into trecce, each braid a hymn to summer. The straw was light as breath, but in its weave lay centuries of work, memory, and pride.

Each Florentine hat was a miracle of meticulous labor: 40 braids, each of 13 threads, sewn in spirals until the wide brim bloomed like a sunflower, a shield against the sun, yes, but also a crown for those who bore the light. If the wheat was the soul of the hat, the women were its heartbeat. The trecciaiole of Signa worked with their hands, their mothers’ hands, and their grandmothers’ hands before them. Their craft was both labor and poetry: braiding under the fading light, whispering songs that melted into the wind. In Fiesole, the bigherinaie interwove straw with silk, cotton, and horsehair to create bigherini, intricate lace-like straw embellishments that shimmered like woven sunlight.

These hats were made not in the rush of factories, but in the rhythm of seasons. The manate bundles passed from one house to another, their journey tracing the intimate map of Tuscan villages. Every brim was not merely sewn but dreamed into shape. And when the hat was placed on a woman’s head, whether in a wheat field or a Milan boulevard, it carried with it the memory of every hand that had touched it.

In 1986, artisans came together under Il Cappello di Firenze to protect the heritage. The opening of Museo della Paglia e dell'Intreccio Domenico Michelacci in 1997 became a shrine to this craft, a temple of woven light and history.

Then fashion found it again. In 2018, Jacquemus unveiled his La Bomba collection: models in colossal straw hats that curved like waves, defiant and romantic, as if the Mediterranean sun itself had been sculpted. Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana followed, weaving tradition into high fashion. The Florentine straw hat became once more what it had always been, a summer crown.

On screen, it flirted with modern mythology. In Sex and the City, Samantha sipped her drink beneath a wide straw brim, the city spinning around her like heat haze. Along the coast of Amalfi and Capri, photographers still chase that same light, half-shadowing faces beneath golden brims.

The story of the Florentine straw hat is a story of journeys. In the 16th century, Cosimo I de’ Medici, ever a patron of beauty and craft, recognized the elegance hidden in this humble sunshade. He gifted these hats to European courts, carrying with them not only Tuscan straw but the whisper of Tuscan summers.

By the 18th century, the little town of Signa had become a kingdom of straw. From its fields to the bustling port of Livorno, the hats were shipped to London, Paris, and beyond. The world came to know them as “Leghorn hats”, but beneath the foreign names, they were still woven from the same golden fields where sunburned sicklemen once wiped their brows.

It was a craft so refined that it became legend. Even Eugène Labiche found inspiration in it, writing his sparkling farce Un chapeau de paille d’Italie, later turned into an opera by Nino Rota in 1945. The Florentine straw hat had become more than a garment, it was a muse.

The Florentine straw hat - Cappello di Paglia is a memory carried on the wind, of wheat bending under August suns, of women braiding under twilight, of ships leaving Livorno’s docks with boxes full of sunlight. It is the feeling of the first breeze that touches your skin when summer has truly arrived.

It protects from the sun, but it also belongs to the sun. It is at once practical and poetic: feather-light, breathing warmth, catching the golden hour and holding it against the world.

A woven circle of tradition and desire. A crown of golden threads. A sunbeam you can wear.