Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani, once described as the world’s most powerful art collector, died in London on November 9, 2014, aged 48. His passing ended a whirlwind chapter in the art market, but his influence continues to shape institutions in Doha and beyond.

Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani, once described as the world’s most powerful art collector, died in London on November 9, 2014, aged 48. His passing ended a whirlwind chapter in the art market, but his influence continues to shape institutions in Doha and beyond.

November 10, 2025

As Qatar’s president of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage from 1997 to 2005, Sheikh Saud paired state ambition with personal connoisseurship to acquire — with unprecedented speed and scale — well over $1 billion worth of works.

His taste ranged from Islamic ceramics and scientific instruments to textiles, jewelry, and photography; he also accumulated cars, bicycles, Chinese antiquities, and more. Much of this material formed the backbone for Qatar’s museum ecosystem, from the Museum of Islamic Art to planned natural history, photography, and costume museums.

A measure of that legacy came into focus years later with “A Falcon’s Eye: Tribute to Sheikh Saoud Al Thani,” the 2020–21 exhibition at Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art. The show and its catalogue celebrated a collector who thought in encyclopedic terms, bridging art and natural history and laying foundations for Qatar Museums’ world-class holdings. In short, it affirmed that his acquisitions were not a spree but a strategy to seed a nation’s cultural infrastructure.

Even a decade on, items he once owned, like the storied “Idol’s Eye” diamond, continue to spark courtroom battles, proof that his footprint on the market remains active as well as institutional.

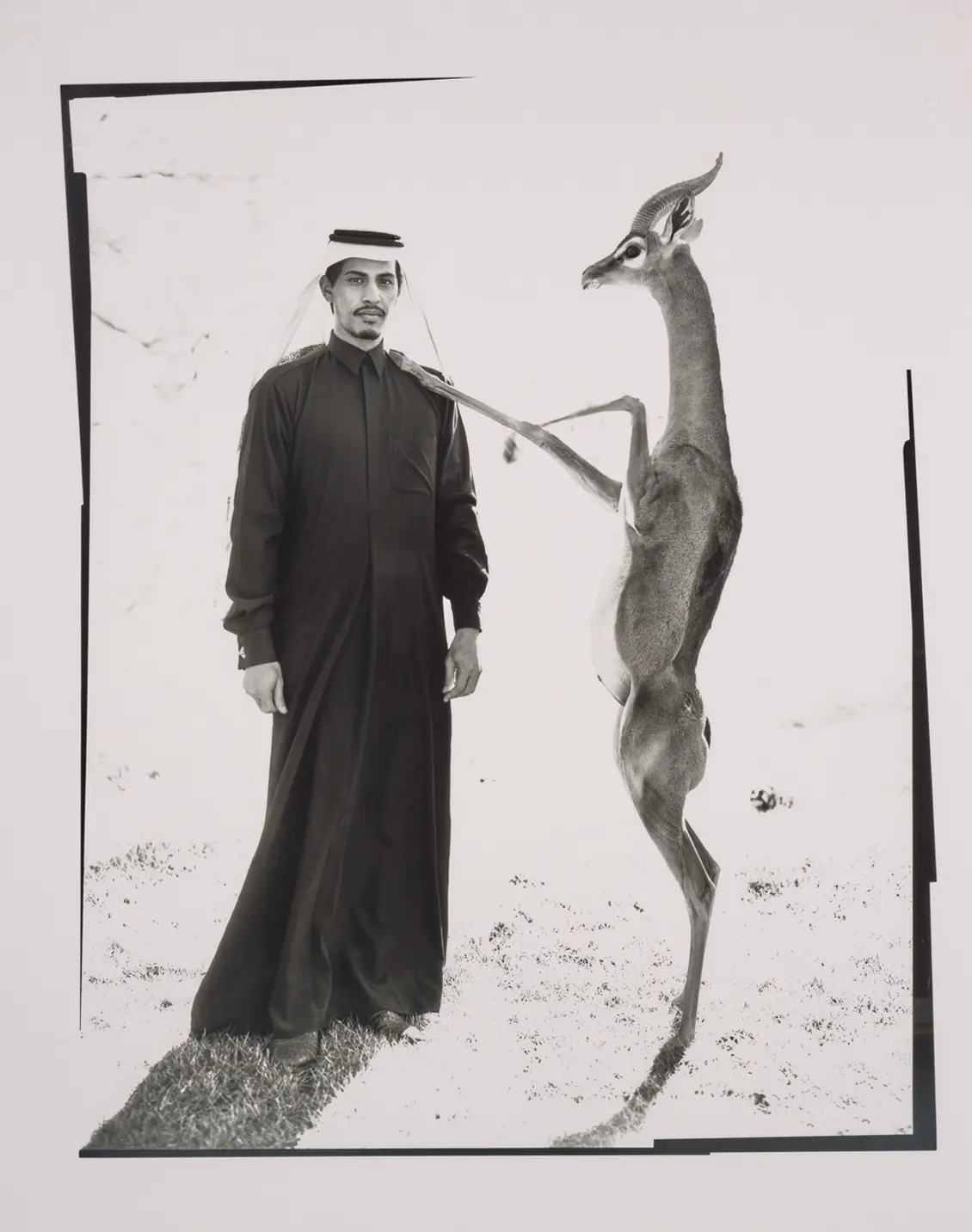

Beyond art, Al Thani’s passion for preservation extended to nature. He founded the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation (AWWP) in Qatar, a private sanctuary devoted to breeding and protecting endangered species, including the Spix’s macaw, Arabian sand gazelle, and Arabian oryx, reflecting his broader vision of safeguarding both cultural and natural heritage.

In the end, Sheikh Saud’s legacy is less about records set than about capacity built. He changed what a young cultural capital could assemble — and and how quickly. Doha’s museums, study collections, and future-facing plans still carry his signature, a reminder that one collector’s eye can redraw a country’s cultural map and recalibrate the global conversation about who stewards art history.