You call it rebellion; punk calls it breathing and nowhere is that more visceral than in punk fashion history. While fashion was sipping, punk started seething. Not stitched for approval, not dressed for deceiving, it bled on the runway and left without grieving.

You call it rebellion; punk calls it breathing and nowhere is that more visceral than in punk fashion history. While fashion was sipping, punk started seething. Not stitched for approval, not dressed for deceiving, it bled on the runway and left without grieving.

November 18, 2025

Forget refinement. Dismiss elegance. Because if you truly want to understand the beating, bleeding heart of modern fashion, you must plunge headfirst into the guttural roar of PUNK. It wasn't a trend; it was a societal purge. And decades after its infamous detonation, this audacious, outrageous, utterly unrepentant force continues to rip through haute couture, dragging it into a defiant new era.

This isn't just a history lesson. It is the core of punk fashion history, a confession of how London’s back alleys created a philosophy so potent it reshaped the DNA of defiance.

Let's get one thing straight: punk subculture fashion isn't, and never has been, something you simply wear. It’s something you embody. It’s one of those infuriating truths that you either have or you don't. And if you don’t, no distressed leather jacket, no meticulously placed safety pin, no towering platform boot can save your soul. The first rule of punk, etched into its very being, is that you don't follow the rules. The second? You really don't follow the rules. This isn’t a fashion statement; it’s a pure, unadulterated act of rebellion, a philosophy translated into ripped seams and defiant glares, forming the backbone of punk fashion history.

We, the modern consumers of culture, parade in our carefully curated "rebellious" looks, stitching on patches we bought online, donning pre-distressed denim. We style ourselves with "edge," but do we truly understand the venom that once coursed through the veins of those who lived it? Do we have a single drop of that uprising within us, or are we merely sanitized copies, playing punk in a world too comfortable to truly defy?

As Afonso Cortez’s Corta-e-Cola: Discos e Histórias do Punk em Portugal (1978-1998) brutally recounts, being punk was no Instagram filter. "Don’t open the English dictionary to know what punk means," wrote António Amaral Pais in Música e Som, 1978. "I’ll tell you: rotten, prostitute, nonsense, meaningless thing or person." He added that if you weren’t punk, you’d look bad, and "if you think you are, even worse."

Rui Maia, from Inkisição, similarly warned, "It’s important to discard the idea that being punk means having spiky hair, ripped clothes... and having an empty head!" This wasn’t a costume; it was a life sentence — the origin story of what would later crystallize in punk fashion history.

Picture it: London, mid-1970s. Not the swinging, vibrant London of Carnaby Street dreams, but a grey, grimy, disillusioned city. Economic malaise was a suffocating fog of mass unemployment and rising poverty. Social mobility was a cruel joke. The youth, stifled by inherited mediocrity and the false promises of their parents' generation, were simmering. They needed an outlet. They needed a match.

Across the Atlantic, the United States wrestled with the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the scandals of Watergate, and the rise of the "New Right," pushing political conservatism and traditional family roles. It was a pressure cooker of discontent, the socio-political climate that later became the foundation of punk fashion history, where aesthetic revolt mirrored social collapse.

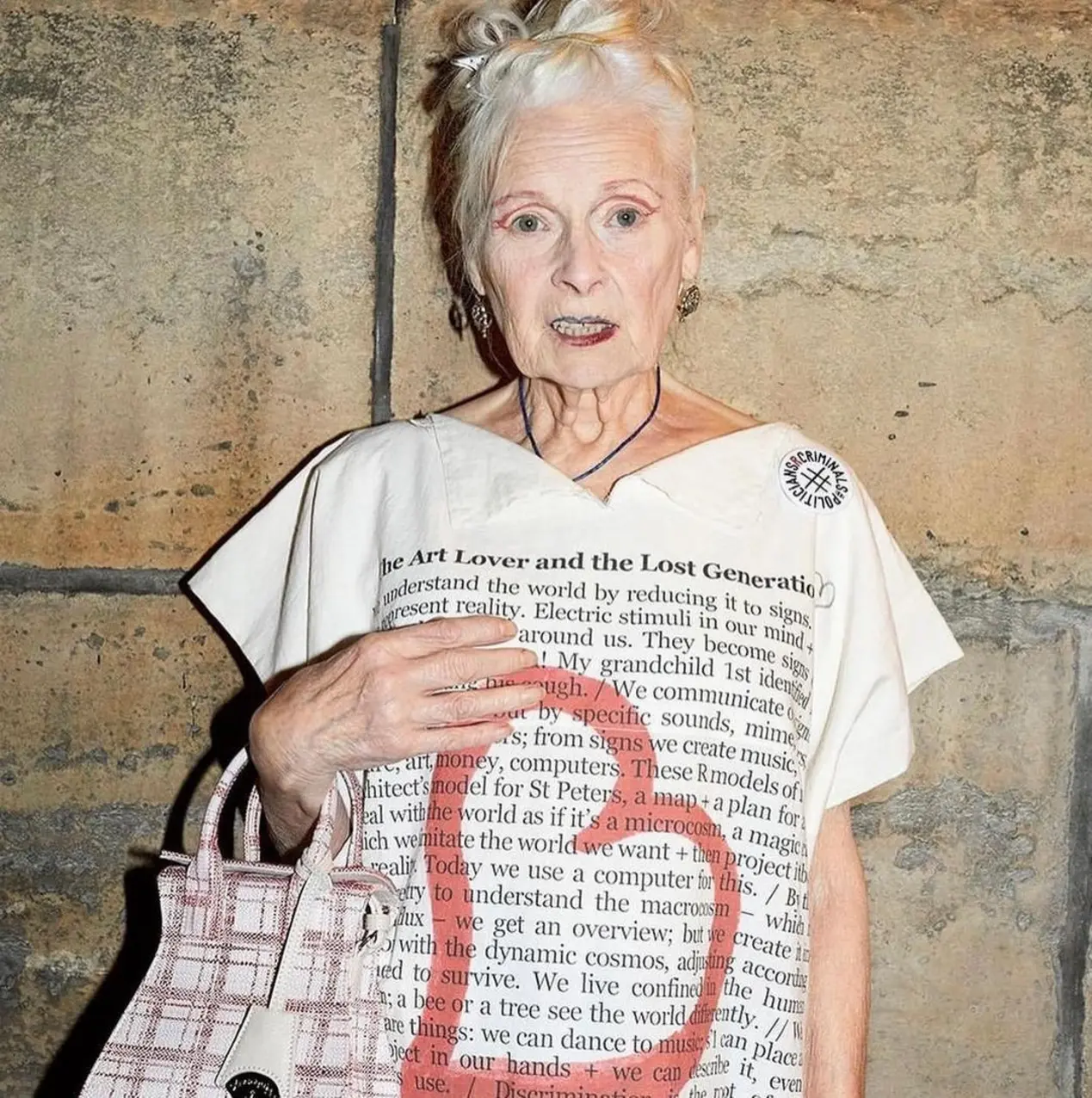

Enter Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. Not designers in the traditional sense, but cultural alchemists, architects of anarchy. Their infamous King's Road boutique, SEX (later Seditionaries), wasn't a shop; it was a psychological warfare outpost, a laboratory for societal deconstruction. Here, amidst the fetishistic paraphernalia, the ripped fabrics, and the provocative slogans, they forged the weapons of a new cultural war.

McLaren, the manipulative Svengali, understood the power of outrage; Westwood, the visionary seamstress of societal malaise, knew how to stitch that outrage into wearable manifestos. Vivienne Westwood punk and Malcolm McLaren punk are now cornerstones cited in every serious study of punk fashion history.

Their muses weren't supermodels; they were the bored, the angry, the dispossessed. Kids with nothing to lose, who found a perverse beauty in ugliness, a blistering truth in rejection. This wasn't about making clothes to sell to the masses; it was about creating a uniform for the revolution, a visual scream against the suffocating silence of conformity. As Westwood herself famously declared, "The only reason I’m in fashion is to destroy the word conformity." This wasn't a quiet rebellion; it was a declaration of war, emblazoned on every garment. They were the first to openly sell leather clothing "full of zippers" at a time when the peace & love movement was still suffocatingly strong. The word "punk" itself, meaning "rotten, dirt, insanity," became their flag, their motto: "No Future."

Punk didn't just break the rules; it vaporized them. It looked at every sacred cow of fashion – elegance, symmetry, precious materials – and spat on them. Its signature wasn't a detail; it was an entire lexicon of deliberate aesthetic terrorism that shaped both punk subculture fashion and its long-term cultural impact.

While the rest of the world was ironing seams, punk was ripping them. Clothing wasn't just distressed; it was violated. Leather, PVC, cheap cotton – hacked, slashed, safety-pinned back together in grotesque mockery of proper tailoring. This wasn't clumsy DIY; it was a deliberate act of aesthetic violence.

A ripped sweater wasn't a mistake; it was a comment on a broken society. Visible seams, raw edges, patches, every imperfection was a badge of honor, a defiant refusal to hide the ugly truths. It screamed: "My world is crumbling, and so is my wardrobe."

This ethos was born from necessity, yes, but quickly evolved into a powerful artistic statement that scholars consistently cite within punk fashion history.

The proud symbol of Scottish aristocracy, of ancient lineage, of inherited wealth and tradition. In punk's venomous embrace, it became a symbol of desecration. Imagine the horror of the establishment as their sacred plaids were sliced into micro-mini skirts, held together by gaping safety pins, paired with bondage straps and spiked chokers. This wasn't merely reappropriation; it was a calculated insult, a middle finger to the notion of inherited privilege — class warfare woven into fabric. As the Painted Ladies documentary, a Vivienne Westwood initiative, quoted Bertrand Russell: "Orthodoxy is the grave of intelligence." Punk proved it, violently. Tartan’s transformation remains one of the clearest examples of cultural sabotage in punk fashion history.

Forget delicate gold. Punk's adornments were salvaged from the industrial wasteland: safety pins, heavy chains, menacing studs, razors. These weren't decorative; they were functional symbols of constraint, chaos, and danger. Safety pins, the "most emblematic symbol of the punk movement", according to Johnny Rotten, weren't just for practicality; they were piercing flesh, holding together garments, declaring that fragility was a strength and that wounds could be beautiful. Chains clanked like weapons. Studs and spikes transformed clothing into armor — a physical boundary between wearer and world. Such elements became visual shorthand for punk subculture fashion and later solidified as a core pillar of punk fashion history.

Slogans and Slashed Silhouettes. Why whisper your dissent when you could scream it on your chest? T-shirts became immediate manifestos, emblazoned with provocative slogans like the "God Save the Queen" desecration, anti-establishment imagery, or crude, visceral graphics. Malcolm McLaren spoke of "messing around with imagery that basically was provocative. If it wasn’t to do with sex, it was to do with politics… It was just imagery that hopefully wouldn’t appear polite." Politeness definitely wasn't a problem; the "Two Cowboys" T-shirt (1975), so incendiary that a customer was arrested under the UK’s 1824 Vagrancy Act for "showing an obscene print in a public place," proved punk's power to provoke beyond clothing.

The silhouette itself was confrontational: skin-tight leather trousers, aggressively short skirts, or oversized, shapeless garments that deliberately distorted the "feminine" or "masculine" ideal. And the black leather jacket? It wasn't just a piece of clothing; it was a second skin. Its maxim: "You can’t steal a biker jacket, you can get one back or strip it down from someone not wearing it or not standing up for it." This was more than fashion; it was a philosophy of ownership, of earning your defiance, a defining trait within punk fashion history and one of the strongest codes of punk subculture fashion.

Hair ceased to be an accessory and became an architectural statement. The Mohawk, often sculpted with sugar water and dyed in unnatural, retina-searing colors like electric blue or shocking pink, was a literal spike of defiance aimed at the heavens. It was an act of visual violence against bourgeois aesthetics, a declaration that beauty could be grotesque, unsettling, and utterly unforgettable. Paired with smeared black kohl, sickly pale foundations, and bruised, defiant lips, punk makeup wasn't about enhancing; it was about confronting. It was a mask of disdain. Even today, the subversive beauty trends of shaved eyebrows and stark, industrial-themed makeup campaigns, seen on TikTok or from luxury brands like Isamaya, trace their lineage directly back to punk's brutal honesty — a lasting echo in punk fashion history.

While Malcolm McLaren gleefully orchestrated the chaos, it was Vivienne Westwood who was punk's true seamstress of rebellion, a "great Englishwoman" who didn't just push fashion history forward but used "all of her power to stand up for the future of the world." Her legacy goes far beyond mere sartorial provocation.

After a painful breakup where McLaren dismissed her as "his mere seamstress," she battled against disrespect and outright ridicule as an untaught designer. Yet, she continued to churn out influential collection after influential collection, proving her raw genius. This period is central to punk fashion history, as Westwood’s vision crystalized punk not only as a style but as a philosophy.

Mark Tarbard, her expert pattern-cutter for the 1981 Pirate collection, recalls watching her work: "She’d made everything herself, on herself. Her method was completely alien to classical fashion education," yet "her genius was that her cut fitted anybody, any size, any sex, and made them look incredible." This was punk's DIY spirit, elevated by an innate understanding of form and rebellion. The Pirate collection, initially "rejected by everyone," found its champion in Grace Coddington at British Vogue, marking a critical turning point for Westwood. She proved that rebellion could be intellectual, artistic, and commercially potent - a critical tension repeatedly explored in studies of punk fashion history.

Westwood's later turn towards historical fashion, like her 1990 Portrait collection featuring rococo paintings on corsets, wasn't "selling out." It was, as she explained, an intellectual continuation of her mission to "destroy the word conformity," to introduce "radical thinking to a dullard modern world dominated by minimalism."

She was a modern-day Boudicca, riding a tank past the Prime Minister's home in 2015 to protest fracking, a "grandmother battling forward in her hand-scrawled Buy Less T-shirt, and to hell with the establishment."

Her final message, shared by her family, was a defiant call to action: "Stop climate change. This is a war for the very existence of the human race... Become a freedom fighter!"

Westwood embodied the ultimate punk paradox: a profound care for humanity expressed through radical, often uncomfortable, confrontation-one of the most defining forces in punk subculture fashion and punk fashion history.

Here lies the punk paradox: a movement born from a visceral hatred of the mainstream, destined to be consumed by it. For years, punk simmered in the underground, a dangerous secret shared by those who dared to defy. But the raw energy was too potent, the aesthetic too magnetic, to remain confined. The fashion industry, ever the vampire, didn't just observe; it devoured. The watershed moment? The Metropolitan Museum of Art's 2013 "Punk: Chaos to Couture" exhibition. On one hand, it was an undeniable validation, a grand acknowledgment of punk's seismic impact. On the other, it sparked a furious debate: Can rebellion truly be housed in a museum? Can "chaos" ever be "couture" without being sanitized, neutered, stripped of its very essence?

This cultural tension has since become a landmark topic within punk fashion history, highlighting the uneasy marriage between rebellion and luxury.

Suddenly, safety pins became precious jewels. Shredded tartan became designer silk. The grime of rebellion was polished into a sheen of sophistication. Celebrities, once horrified by its aesthetic, now sported punk "looks" on the red carpet. Was this homage, or was it the ultimate act of appropriation? Did Madonna's Riccardo Tisci spiked jacket elevate punk, or simply turn it into another costume? This uneasy truce between anarchy and elegance remains one of punk's most uncomfortable and fascinating legacies — a core discussion in modern punk fashion history scholarship.

Designers, from Gianni Versace to John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, Jean Paul Gaultier, Anna Sui, and Comme des Garçons, wrestled with punk's powerful shadow. Gianni Versace's 1994 Safety Pin dress, famously worn by Elizabeth Hurley, transformed the punk emblem into high fashion, its "majestic golden crystal-encrusted kilt pins" holding together elegant, slashed couture. Was it irony or genius? John Galliano's 2006 Dior Garbage Bag dress, worn by Kirsten Dunst and photographed by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue, was a high-fashion take on British punks' desperate use of actual bin bags during the UK's 1978-79 "Winter of Discontent" — a direct confrontation of taste, yet dressed up for the elite. All these moments form essential case studies within punk subculture fashion entering luxury fashion.

Naomi Campbell's iconic fall at Vivienne Westwood's Fall/Winter 1993 show – toppled by nine-inch mock crocodile shoes – became a defining moment. "It was really beautiful when you fell, it was like a gazelle," Westwood later told Campbell. This "disaster" became a "real moment," sparking new opportunities for Campbell, with designers "jealous of 'the press that you got'." It was a powerful metaphor for punk itself: a disruptive act that, against all odds, yielded unexpected, profitable results. This moment is often cited in fashion studies analyzing pre-and-post assimilation in punk fashion history.

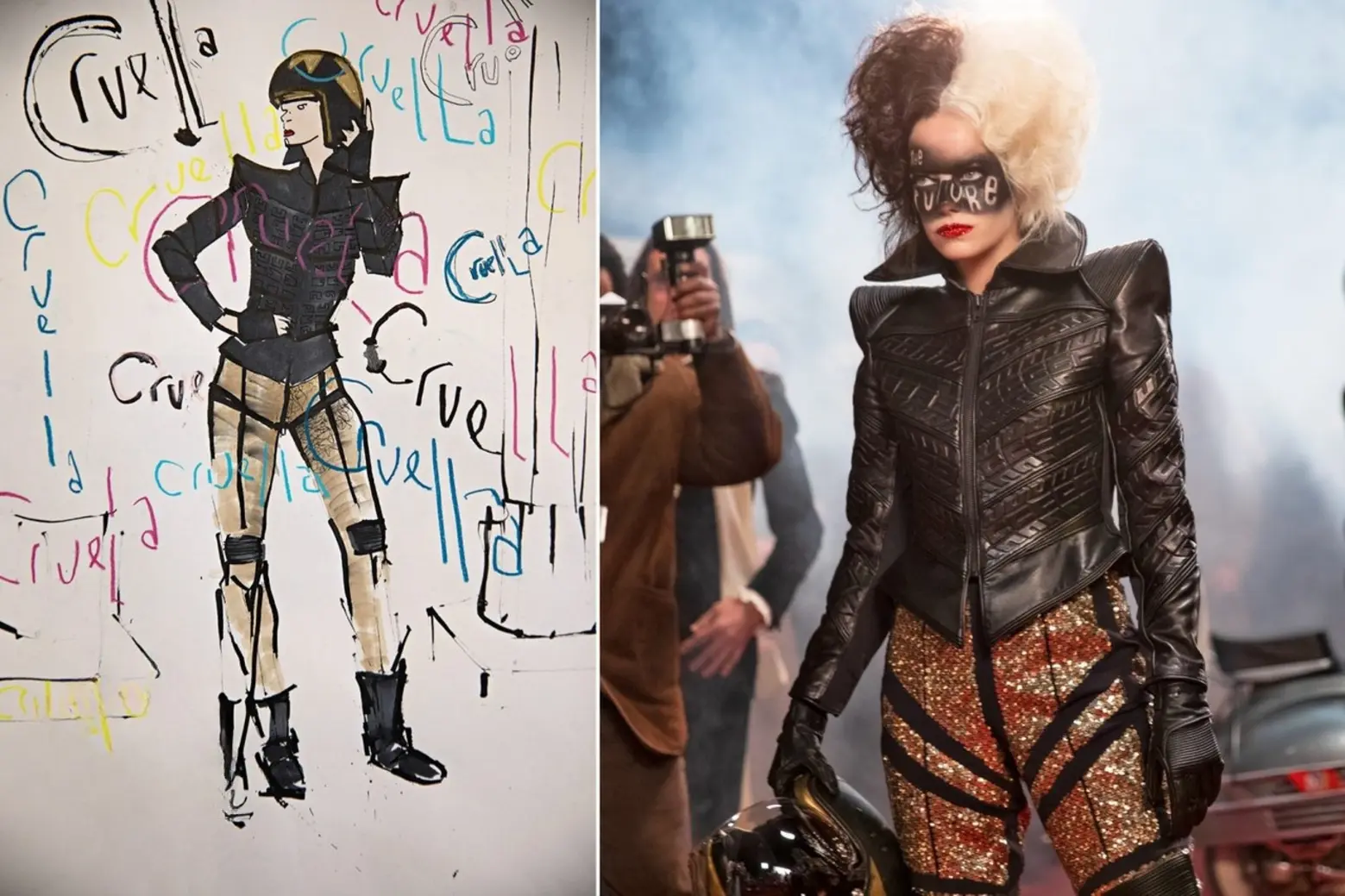

Even Disney, the ultimate purveyor of sanitized fantasy, dared to dabble. Cruella (2021) reimagined the iconic villain through a punk lens, dressing her in leather gowns, metal hardware, and deconstructed Dalmatian prints. Costume designer Jenny Beavan masterfully captured the aesthetic, particularly the raw, almost violent transformation of Estella into Cruella. Yet, could a corporate behemoth truly grasp the spirit of a movement born to dismantle corporate power? The film became a testament to punk's enduring visual power, but also a haunting question: when the ultimate rebels are consumed by the biggest machines, what truly remains of their rebellion?

The answer is complex: high fashion doesn't just appropriate; it reflects. It takes the raw, visceral energy of the street and translates it, often imperfectly, into a language the mainstream can understand. It dilutes the poison, yes, but in doing so, it ensures the radical idea, the disruption lives on, influencing generations who may never know its grimy origins.

Punk didn't die; it mutated. It fragmented. It seeped into the collective unconscious, becoming the silent antagonist to every bland trend, every fleeting fad. Its legacy isn't just visible in the occasional studded jacket or ripped jean on a runway; it's embedded in the very fabric of how we conceive of fashion, authenticity, and rebellion.

Vivienne Westwood herself, the eternal provocateur, exemplified this uneasy evolution. The woman who scandalized a nation with "God Save the Queen" desecrations later became a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 2006, accepting her OBE in 1992 while famously twirling her skirt knickerless for the paparazzi. This was her final, hilarious act of defiance against the very establishment honoring her. She proved you could wear the crown and still mock the kingdom. Alexander McQueen's 2008 "God Save the Queen" dress, rendered in embroidered and bejeweled silk, showed a more "refined and reverential" take on the same slogan — a sign of how punk's sharp edges can be dulled, even by its inheritors. Even in its evolution, Vivienne Westwood punk remained inseparable from the DNA of punk fashion history.

So, next time you see a safety pin on a runway, a torn hem on a celebrity, or a flash of vibrant, unnatural hair, don't just see a trend. See the echo of a revolution. Hear the guttural roar of defiance. Feel the raw, untamed heart of punk still beating beneath the polished veneer of high fashion. Because in a world that constantly tries to dictate who you should be, punk remains the ultimate, dangerous permission slip to be exactly, defiantly, and outrageously, yourself. And for that, we should all be eternally grateful – and a little bit terrified.Are you ready to embrace the chaos, or will you remain safely in your pristine prison of conformity?