April 13, 1990 - Chiba, Japan. On the opening night of Madonna’s Blonde Ambition World Tour, a single gesture changed fashion history: she slipped off her pinstripe jacket and revealed Jean Paul Gaultier’s now-mythic pink satin cone bra.

April 13, 1990 - Chiba, Japan. On the opening night of Madonna’s Blonde Ambition World Tour, a single gesture changed fashion history: she slipped off her pinstripe jacket and revealed Jean Paul Gaultier’s now-mythic pink satin cone bra.

December 6, 2025

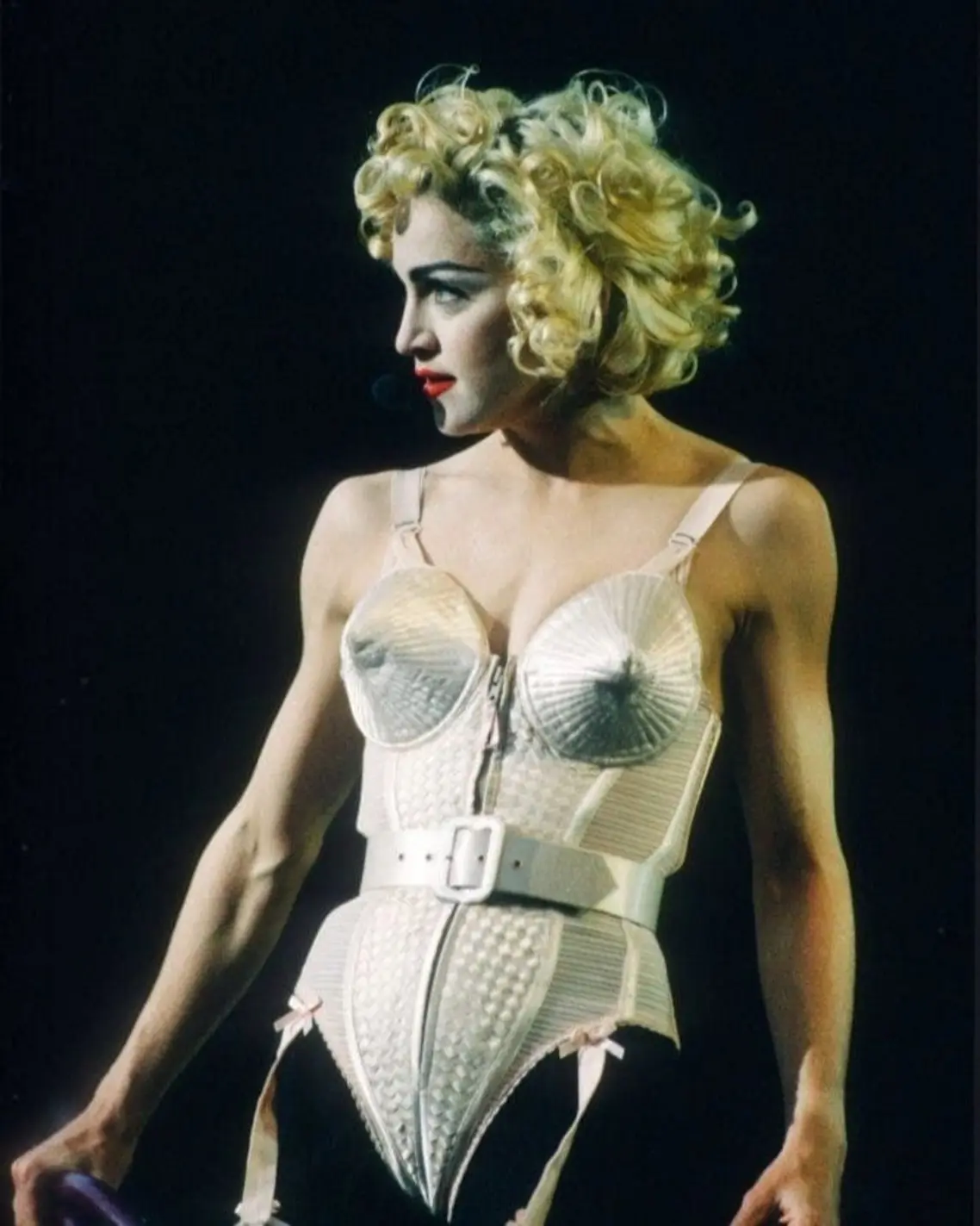

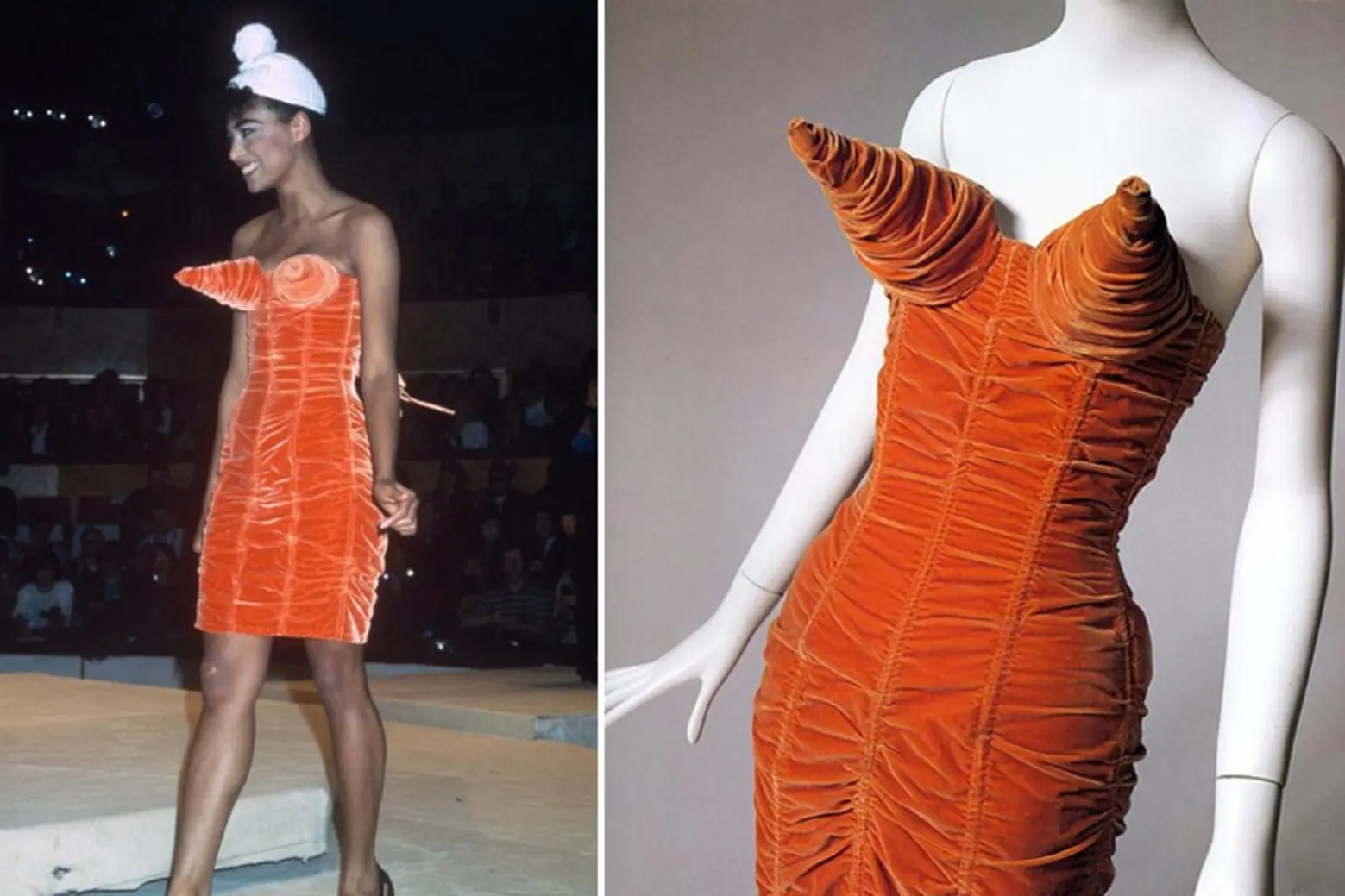

Long before Madonna made it a global symbol, the cone bra already belonged to Jean Paul Gaultier’s world of irreverence. In Fall/Winter 1984–85, within the “Barbès” collection—a chaotic, multicultural love letter to a Paris neighborhood—Gaultier sent out a ruched velvet corset dress with pointed breasts. It carried the charge of lingerie that had slipped out of the boudoir and refused to return.

The early cone silhouette had deep roots: Gaultier grew up fascinated by corsetry—the satin, the salmon pink, the flesh-toned sheen of vintage underpinnings. But in his hands, these symbols of containment became playful weapons. He exaggerated the cups; he exposed the engineering; he inverted the original purpose.

If the 1940s and ’50s bullet bras created a fantasy of hyper-femininity: Hollywood starlets with “sweater girl” curves, Gaultier turned that fantasy sideways.

When Madonna walked out in Chiba on April 13, 1990, opening the Blond Ambition World Tour, the audience first saw a pinstripe suit: masculine, sharp, almost austere. It was a silhouette that nodded to business power dressing, the corporate armor of the late ’80s. For a moment, it looked like she was about to play by the rules.

Then the jacket slipped open. Purpose-cut slits revealed a flash of pale pink satin beneath, and suddenly the entire visual language shifted. The cone bra—geometric, surreal, almost weapon-like—peeked out as if it were breaking free from the constraints of the suit. The crowd’s response was instant: shock, delight, scandal, electricity. Madonna was truly setting off a cultural explosion.

What made the moment historic wasn’t the garment itself but the collision it staged. Madonna’s athletic body carried the cone bra with authority, not as an accessory to seduction but as a tool of domination. Feminine softness, rendered in rigid geometry, suddenly looked militant.

In that single gesture, Madonna recast the meaning of the bullet bra. No longer a relic of mid-century fantasies, it became a manifesto that argued women could weaponize the very symbols once used to contain them.

It was Madonna telling the world that if fashion had once dictated how women should appear, she was now dictating how fashion should behave.

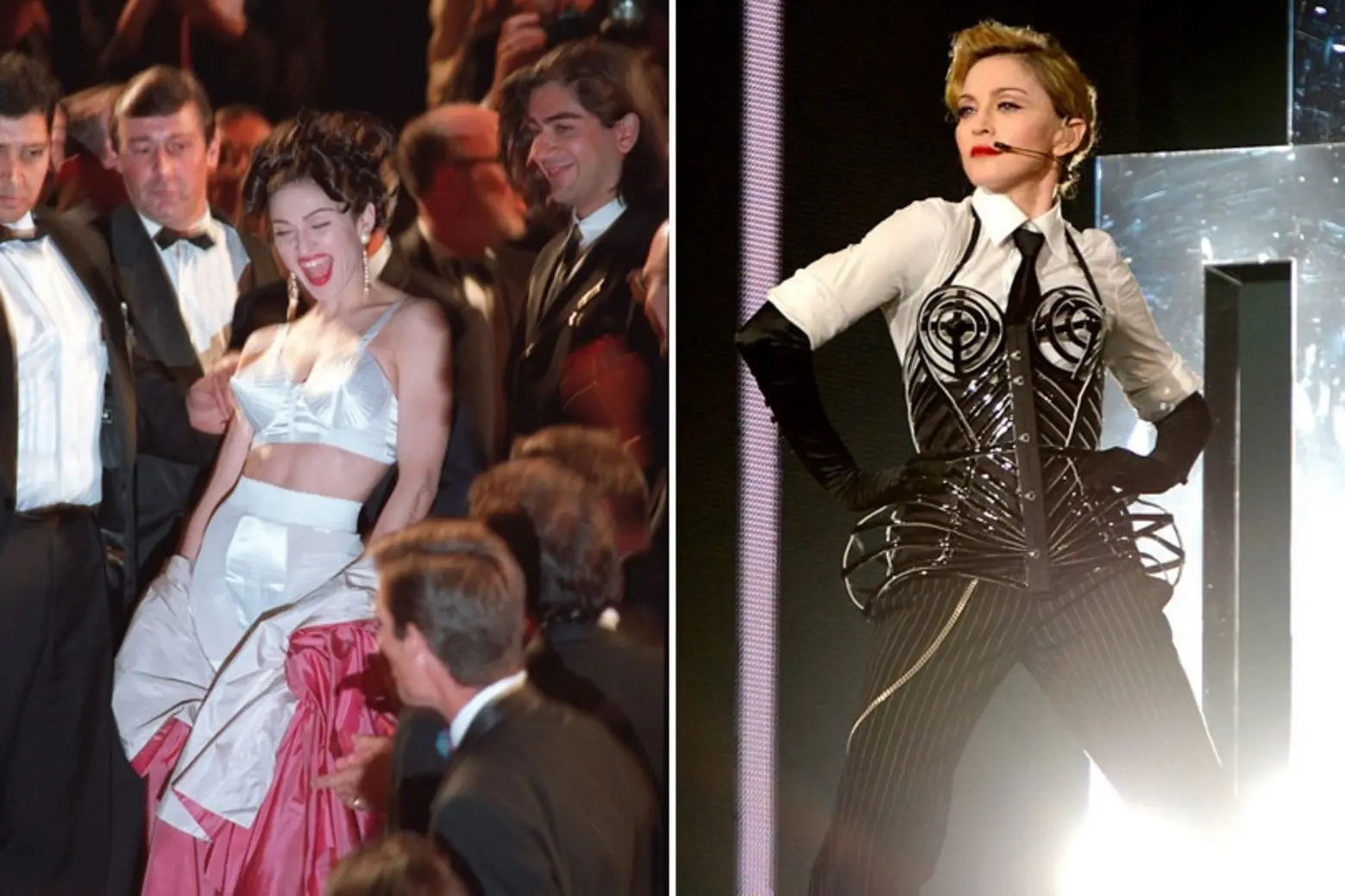

Madonna wore new variations of the bra - to Cannes in 1991, on tours in 2012, in editorial reinterpretations - but each iteration served the same purpose: reminding audiences that fashion can be both camp and confrontation.

Gaultier himself later said it was one of the great collaborations of his career. Not because he designed a costume that became famous, but because Madonna understood what the cone bra meant. Using the spikey piece, she amplified it until it rewrote pop culture’s vocabulary.

Decades later, the image remains instantly recognizable. Pointed cups, satin sheen, a woman who refused to be quiet. Fashion rarely gets to redefine the body, but on that night in January 1990, it did exactly that.