Taste is supposed to guide us, to keep us safe from the embarrassing, the silly, the overdone. But what if taste is the real trap, and the escape is kitsch?

Taste is supposed to guide us, to keep us safe from the embarrassing, the silly, the overdone. But what if taste is the real trap, and the escape is kitsch?

October 29, 2025

Taste is supposed to guide us, to keep us safe from the embarrassing, the silly, the overdone. But what if taste is the real trap, and the escape is kitsch?

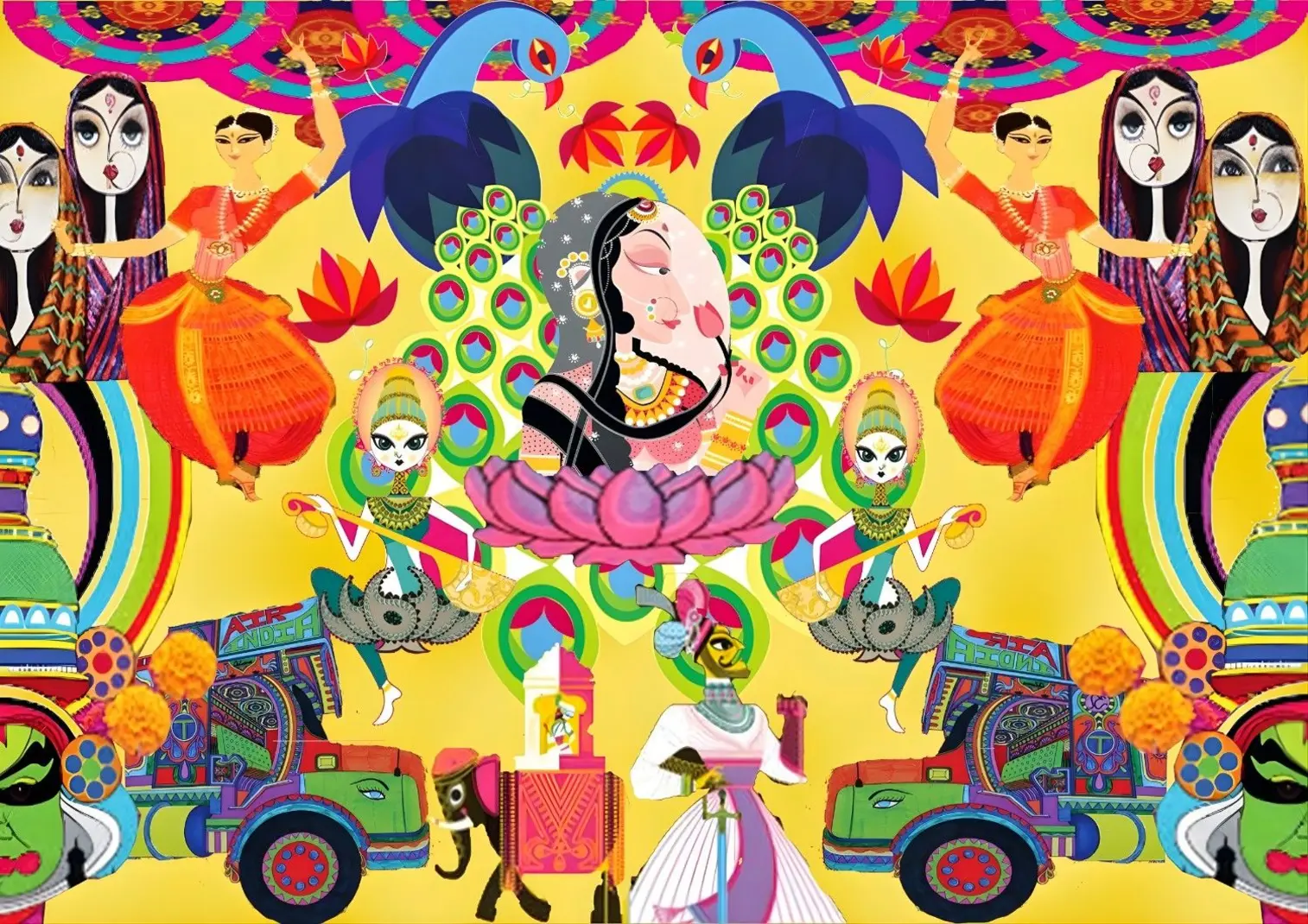

Step into this unruly, sugar-rushed aesthetic, a place where seriousness is banned at the door, irony shares a cocktail with sincerity, and where the forbidden fruit of “bad taste” ripens into something irresistible.

Kitsch dares you to laugh, but it also dares you to love.

There is nothing quiet about kitsch. It whispers in neon, it sighs in sentimental melodies, it parades in the awkward, the cute, the saccharine. It is childhood and memory, but also rebellion and audacity. For decades, critics rolled their eyes at its sweetness, called it cheap, fake, or vulgar. Yet kitsch didn’t disappear. And now, here it is, back on center stage, dancing shamelessly.

Why does it pull us in so strongly? Because kitsch is not really about objects; it’s about us. It feeds the hunger for comfort in a fractured world, it relishes in imperfection when perfection suffocates, it is the giggle in the museum, the tear during a soap opera, the guilty pleasure that feels far too good to be guilty at all. Kitsch thrives because it doesn’t apologize. And deep down, neither do we.

So kitsch me if you can. Try to resist the lure of the sentimental, the exaggerated, the “too much.” Try to hold on to your composure while the colors swell, the sweetness drips, the ridiculousness winks back at you. You may try to look away, but kitsch already has you.

It is fascinating to consider how the once-maligned concept of kitsch has not only found a place in contemporary culture but has also become a celebrated aesthetic, particularly within fashion and design, representing a significant shift away from traditional notions of “good taste.” What was once a term of scorn has been reimagined as a vocabulary of self-expression, a maximalist manifesto, a playground where “bad taste” becomes irresistible.

But this shift did not happen overnight. Kitsch has taken a long, complex journey, from the art markets of 19th-century Munich, through its demonization by modernists, to its triumphant revival in Pop Art and fashion. Along the way, kitsch has carried multiple burdens: accused of being vulgar, sentimental, cheap, and shallow.

Why? Because kitsch is not merely a style, it is a spirit. It is rebellion against elitism, nostalgia against cynicism, excess against minimalism. It is the unapologetic joy of more-is-more.

The word kitsch first appeared in the 1860s–1870s in Munich’s art markets, where dealers used it to dismiss cheap, mass-produced images sold to the growing middle class. These were not works of “true” art but sentimental reproductions—landscapes, portraits, religious imagery, designed to appeal to buyers without aristocratic training in taste. Kitsch was thus born as an insult, a way for the cultural elite to gatekeep beauty.

For modernist thinkers like Clement Greenberg, kitsch was the antithesis of avant-garde art. In his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Greenberg described it as mechanical and formulaic, a parasite on true creativity, designed to trigger easy emotions rather than intellectual depth. In his view, kitsch was not simply bad, it was dangerous, a form of cultural regression.

The comparison was stark. Avant-garde art pursued abstraction, ambiguity, disinterest. Kitsch trafficked in pathos, sentiment, recognizability. It was, in Greenberg’s terms, the sugar that dulled the masses.

But here lies the paradox: what the modernists dismissed as weakness, the immediate recognition, the sentimental pull, is precisely what makes kitsch enduring. Unlike abstract art, which demanded education and patience, kitsch offered instant pleasure, a democratic beauty accessible to all.

In 1935, sociologist Elias Norbert predicted that kitsch might one day be reevaluated positively. He was right. In 1998, Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum embraced kitsch outright, publishing On Kitsch to argue that its core values, sentimentality, pathos, learning from past masters, were not failures but strengths. As Nerdrum declared: “I am a kitsch painter.”

This was a turning point. Kitsch was no longer the shadow of art but an alternative philosophy of beauty.

The mid-20th century marked kitsch’s dramatic comeback: Pop Art.

Artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein deliberately embraced the aesthetics of the mass-produced and the sentimental. Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans, his Brillo boxes, his Marilyn Monroes, all unapologetically kitsch. He didn’t disguise the vulgarity of repetition or consumerism; he celebrated it.

This was not incompetence but provocation. Pop Art asked: If millions of people love Campbell’s soup, why can’t it be beautiful? If Marilyn’s face can be endlessly reproduced, why can’t it be sacred?

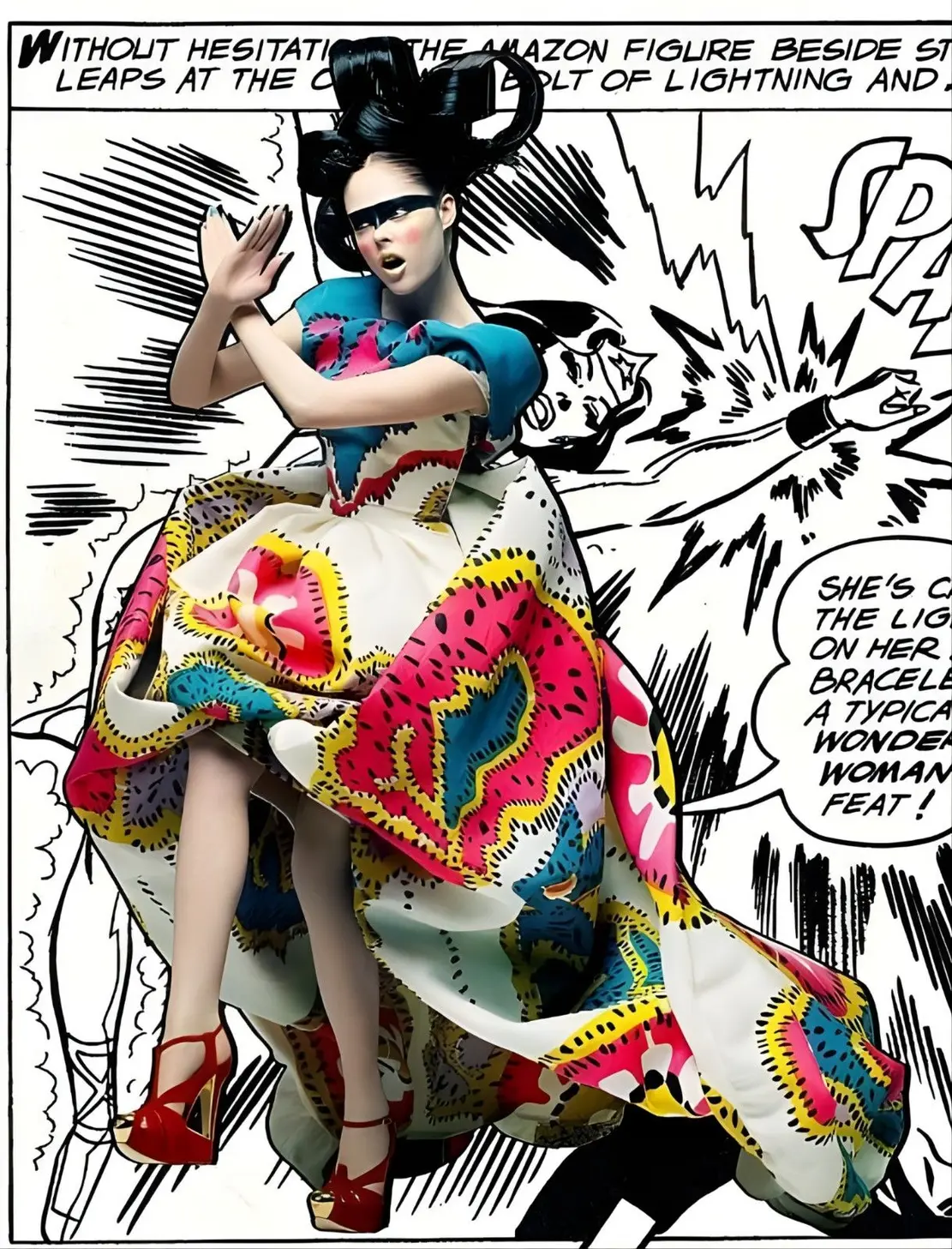

Fashion quickly picked up the thread. Versace’s baroque prints, Moschino’s ironic slogans, Prada’s comic book motifs, all owe a debt to Pop Art’s revalorization of kitsch. By the late 20th century, kitsch was no longer a taboo; it was a luxury.

In fashion, kitsch is that delightfully defiant style that unapologetically embraces the joyful and the sentimental, standing in stark contrast to the serious world of highbrow design. It's not just about wearing a lot of stuff, even though it often feels like maximalism on a sugar rush; nor is it simply a sarcastic wink, though irony is its favorite accomplice. The true spirit of kitsch in fashion is a cheeky mix of three key ingredients. First, there's a heaping dose of sentimentality, where clothes and accessories are less about looking cool and more about feeling things, from the bubbly nostalgia of Hello Kitty charms and heart-shaped bags to the melodramatic charm of a “Boy with the Tear” print.

Next is its effortlessly recognisable, kitsch is a visual language that doesn’t need a dictionary. You immediately get the joke, which needed no theoretical essay to be understood; its genius was in its blatant, instantly recognizable "bad taste." This brings us to the third and most crucial element: the reframing of bad taste. Kitsch revels in the gaudy and the cliché, piling on rhinestones, cartoon prints, and clashing colors, but it does so not as a mistake but as a statement of pure, unadulterated joy. As philosopher Tomáš Kulka argued, kitsch is beautiful and emotional, immediately accessible, and profoundly uncomplicated. It makes no pretense of deepening our knowledge; it simply offers pleasure without shame. And in a world obsessed with intellectualizing every aesthetic choice, that unapologetic, guilt-free pleasure is its most profound act of rebellion.

Nicki Minaj, Katy Perry, and Lady Gaga burst onto the scene as fashion’s brats, using kitsch to jolt pop culture awake. Minaj came armed with neon wigs and candy-colored chaos, a bratty refusal to play it safe in hip hop’s uniform world.

Katy Perry’s California Gurls video turned pop into pure kitsch, with the singer strutting through a candyland of cupcake bras, whipped-cream cannons, and neon fantasy.

Gaga turned shock into spectacle, Mickey Mouse bodysuit, bow wigs, even a stuffed-animal frock, proving that pop could still provoke. Together they showed that kitsch, loud and unruly, wasn’t just style but a declaration, messy, mesmerizing, and impossible to forget.

The runway has always been a stage for transformation, a place where designers push the limits of fabric, form, and fantasy. But when it comes to kitsch, the runway does something more audacious: it dares to treat “bad taste” not as a flaw but as a creative currency. The kitsch spirit thrives most freely in collections that abandon restraint altogether, where parody, excess, and flamboyance fuse into a carnivalesque spectacle. To see how deeply this aesthetic is engraved into fashion’s imagination, one only needs to revisit the delirious theater of John Galliano at Dior’s Spring 2005 show and the outrageous playground of Jeremy Scott’s Moschino in Spring 2022 and 2023.

When Galliano unveiled Dior’s Spring 2005 ready-to-wear, it felt less like a collection and more like a fever dream staged under the spotlights. The spirit of kitsch pulsed through every detail, testing the boundaries of what Dior, a house synonymous with elegance and refinement, could contain.

The silhouettes themselves were loud declarations of excess. Models strutted in bubble skirts made of synthetic satins, puffed like overblown party balloons, cinched at the waist with corset belts that seemed stolen from a costume trunk. Rather than whispering refinement, the garments shouted spectacle, reveling in their own theatrical absurdity. Candy-colored mini crinolines layered in plastic-like sheens recalled the wardrobes of toy dolls, blurring the line between couture and carnival.

Galliano’s genius lay in his ability to juxtapose contradictions until they exploded into kitsch glory. A gilded corset paired with hot-pink leggings, embroidered denim cut-offs worn alongside aristocratic bustiers, biker jackets studded with rhinestone flames draped over chiffon skirts, each look dismantled the hierarchy of “high” and “low” taste. Nothing was sacred, and that irreverence became the point.

The cultural mash-ups were equally audacious: geisha-inspired robes colliding with French Rococo frills, aristocratic silhouettes tangled with biker-girl bravado. Galliano turned Dior into a masquerade, where meaning dissolved into pure visual pleasure. Journalistically speaking, he was interrogating Dior’s own codes, asking, perhaps, what happens when refinement gets drunk on its own history. The answer was there in plain sight: a delirious carnival of chiffon cupcakes, plastic accessories, and boudoir lingerie painted in cartoon colors.

Galliano’s 2005 Dior wasn’t parody for parody’s sake. It was proof that kitsch could be power, that an aesthetic once dismissed as vulgar could occupy couture’s most hallowed house and leave behind a legacy of audacity.

Fast forward nearly two decades, and kitsch found a new prophet in Jeremy Scott. His Moschino Spring 2022 collection staged what might best be described as Jackie O gone paper doll. Here, kitsch operated as caricature, flattening sophistication into cartoon parody.

Models marched out in boxy pastel skirt suits with outsized buttons, outfits that looked less like garments than 2D illustrations of Chanel tailoring. Candy-colored pillbox hats perched on heads, accompanied by dainty gloves that tipped into absurdity, turning elegance into a dress-up game. The result was uncanny: models looked like figurines in a toy shop window, trapped between fashion and fantasy.

The details sealed the kitsch transformation. Ducks, teddy bears, and zoo animals embroidered onto prim twinsets blurred Park Avenue polish with nursery playtime. What Galliano did with Rococo excess, Scott did with childhood motifs, dismantling sophistication until it collapsed into silliness. Yet beneath the sugar rush was critique: Moschino’s SS22 was a satire of class performance, showing how easily refinement could be reduced to a cartoon.

If SS22 was kitsch through caricature, SS23 was kitsch through object absurdity. Scott turned the runway into a surreal swimming pool, attaching inflatable floaties to cocktail gowns and lifebuoys to eveningwear. Couture became carnival, its elegance punctured, literally by beach props.

The message was clear: if the world is drowning in crisis, Moschino insists fashion can be your life jacket. It was a collection that celebrated excess, parody, and joy, a reminder that sometimes the most frivolous aesthetics carry the most necessary relief. Scott didn’t just design clothes, he built a buoyant metaphor, positioning himself as fashion’s eternal pool boy, keeping the industry afloat with irony and laughter.

Across these examples, what emerges is a portrait of kitsch not as accident but as deliberate rebellion. On Dior’s runway, kitsch was opulence pushed to its breaking point, collapsing into carnival. At Moschino, kitsch was satire: a weaponized parody of fashion’s own seriousness. Both proved that kitsch, once dismissed as vulgar, now provides fashion with one of its richest vocabularies of expression.

To dismiss kitsch as “too much” is to miss its point. Its very exaggeration, its collisions of high and low, its humor and naivete, these are the tools by which fashion critiques itself. On the runway, kitsch is not an embarrassment but a mirror, reflecting back the absurdities of taste, wealth, and aspiration. When Galliano sent out chiffon cupcakes and Scott strapped lifebuoys to gowns, they weren’t destroying couture but liberating it, proving that beauty could be found in chaos, parody, and even bad taste.

Kitsch on the runway is not timid, and it is not apologetic. It is fashion in its most outrageous mood: exuberant, naughty, and unafraid to turn elegance into a punchline. And perhaps that is why it endures, because in a world obsessed with perfection, kitsch reminds us that fashion’s truest spirit is play.

Kitsch has always found its own naughty way forward, slipping into fashion’s bloodstream like a mischievous child who knows how to get exactly what they want. It is bratty, feisty, and gleefully disobedient, never asking for permission but always demanding attention. On the runway, it doesn’t sit quietly, it stamps its feet, makes faces, and throws glitter in the air of seriousness. In this sense, kitsch is fashion’s eternal brat: insolent yet irresistible, crude yet creative, mocking yet magnetic.

Its bratty nature thrives in hybrid forms.

With Viktor & Rolf, kitsch takes on a conceptual avant-garde identity, still bratty but with sharper teeth. Their sculptural gowns, duvets draped as couture, dresses framed like paintings, or ballgowns collapsing sideways, embody kitsch’s instinct to mock convention while turning mockery into art. Text scrawled across gowns, ironic slogans, and surreal constructions all underline kitsch’s love of provocation. The shows are installations as much as fashion, a brat smashing the gallery glass just to see what happens.

At GCDS, it meshes with streetwear to produce cartoon-scale hoodies, slime-green latex, and JigglyPuff pop-ups, fashion as oversized toys, deliberately juvenile yet styled for adults.

In all these expressions, kitsch’s essence remains the same: experimental, excessive, and unafraid to look ridiculous. It is a brat who laughs at rules, a feisty spirit that keeps fashion alive by refusing to take beauty too seriously.

The psychology of kitsch is less a clinical explanation than a love story with all things gaudy, glittering, and excessive. To step into the world of kitsch is to be seduced by its playful vulgarity, its unapologetic brightness, its ability to turn bad taste into something not just tolerable but irresistible. The question of why kitsch has become so dominant today is answered not by theory alone but by emotion. It tugs at memory, delights in irony, and above all creates a shared language that needs no translation.

Part of its magnetism comes from nostalgia. In a world where tomorrow often feels uncertain, kitsch offers a return ticket to a past imagined in Technicolor. Plush toys dangling from handbags, kawaii figures grinning from sweatshirts, and heart-shaped motifs splashed across denim are not simply decorations, they are bridges to the safety of childhood. They whisper of birthday parties, toy shops, cartoons on television, and the uncomplicated joy of collecting stickers or candy wrappers. This sentimentality might be dismissed as frivolous, but it has a psychological pull stronger than logic, reminding us of a time when happiness was immediate, tactile, and unfiltered.

At the same time, kitsch thrives as a form of counterculture. Social media has polished everyday life into an endless parade of curated perfection, where minimalism often reigns with its beige walls, neutral wardrobes, and carefully balanced lattes. Against this tyranny of flawlessness, kitsch bursts forth in sequins, rhinestones, plastic charms, and intentionally garish colors. It laughs at austerity, replacing the clean lines of restraint with a riot of pattern and sparkle. Its humor is its rebellion: a glittery unicorn patch mocking the solemnity of a monochrome feed, a plastic keychain defying the leather-bound seriousness of luxury minimalism. In its gaudy exaggeration, kitsch feels more honest, because life itself is rarely so tidy.

There is also an irresistible accessibility to kitsch. Where minimalism can appear elitist, available only to those with the means and discipline to pursue “less but better,” kitsch invites everyone in. A smiley face needs no cultural education, a cartoon bunny requires no translation, a rhinestone heart shines for anyone willing to enjoy its sparkle. It is democratic in spirit, uniting generations and subcultures through symbols that are universal in their cheerfulness. This inclusivity explains why Gen Z and millennials, generations fluent in irony but hungry for authenticity, have embraced kitsch as a second skin.

Far from naïve, kitsch in fashion is deeply strategic. It transforms silliness into power, using color and excess as a weapon against cynicism. In an age often weighed down by seriousness, climate anxiety, and political tension, kitsch emerges as a survival strategy: to dress in kitsch is to proclaim joy as resistance. It insists that sincerity and humor can coexist, that wearing a rhinestone-encrusted cherry necklace can be just as valid an act of self-expression as donning a perfectly tailored black blazer. It invites us into a colorful, naughty world where irony sparkles and nostalgia dances, and in that realm, the line between bad taste and brilliance vanishes completely.

Kitsch is not static; it evolves.

It asks: Why not? Why not dance in cutlery? Why not carry a pigeon-shaped clutch? Why not love what elites call ugly?

Kitsch liberates us from shame. The triumphant reign of kitsch signifies a broader cultural maturity: we are comfortable enough to embrace imperfection, sentimentality, and humor. Fashion once sought to correct “bad taste”; now it thrives on it.

Kitsch is no longer a guilty pleasure, it is a critical language, a way of rebelling against elitism, a joyful reclaiming of mass culture. It tells us that beauty is not universal, not fixed, not serious, but playful, nostalgic, and deeply human.

And perhaps that is why kitsch matters. Because in the end, what is fashion if not a game of exaggeration, a theater of dreams, a dance of bad taste turned glorious?