Born from Cecil Rhodes’s supply empire and perfected by the Oppenheimers’ advertising genius, De Beers turned a geological commodity into the most legible proof of love.

Born from Cecil Rhodes’s supply empire and perfected by the Oppenheimers’ advertising genius, De Beers turned a geological commodity into the most legible proof of love.

January 19, 2026

Before 1888, a diamond was just a shiny rock found in a South African hole. After Cecil Rhodes got his hands on it, it became an economic system. By the time the Oppenheimers were finished with it, it was a biological necessity. Cecil Rhodes built the engine first, consolidating South Africa’s scattered mining claims until supply could be managed and monopoly could pass for destiny. In 1947, “A Diamond Is Forever” sealed the deal, transforming the diamond engagement ring from a choice into a social requirement.

The diamond rush around Kimberley was an extraction scramble where fragmented operators flooded the market and price volatility punished anyone who lacked scale. In that environment, Cecil Rhodes rose by treating diamonds less as glitter and more as an economic system. Through the 1880s he pursued a deliberate program of consolidation, buying and combining claims until fragmented production could be coordinated under one corporate structure.

What the 1888 consolidation created was a platform for market influence. A diamond’s premium depends on scarcity feeling believable, and believability comes from control. Early De Beers practice focused on stabilizing prices by regulating the flow of rough stones through coordinated purchasing and disciplined release. It solved the industry’s core paradox: abundance underground, fragility at the counter. The “natural preciousness” of diamonds has always relied on an engineered ecosystem that treats supply like a valve, not a flood.

This same structure became the quiet power behind De Beers’ cultural takeover. With mines consolidated and supply effectively integrated into one system, De Beers could invest aggressively in global advertising with unusually clean incentives: any rise in diamond demand would circle back through the channels it controlled.

By the 1930s, De Beers hit a wall: diamonds were becoming dangerously common. When a luxury becomes too "available," it loses its sparkle and, more importantly, its price tag. To save the bottom line, De Beers and the ad agency N.W. Ayer & Son didn't just tweak an ad, they performed a lobotomy on global courtship rituals. They stopped selling rocks and started selling "emotional insurance," effectively birthing the modern engagement ring tradition out of thin air.

The genius of the strategy was converting invisible feelings into a public, measurable signal. Romance is famously hard to track, so De Beers offered a material receipt. They convinced men that the depth of their devotion was directly proportional to the size of the rock, while simultaneously dispatching "educational" representatives to high schools to train teenage girls to view a diamond as the only acceptable finale to a proposal. It was a new kind of social arithmetic where love was the variable and the price of the ring was the constant.

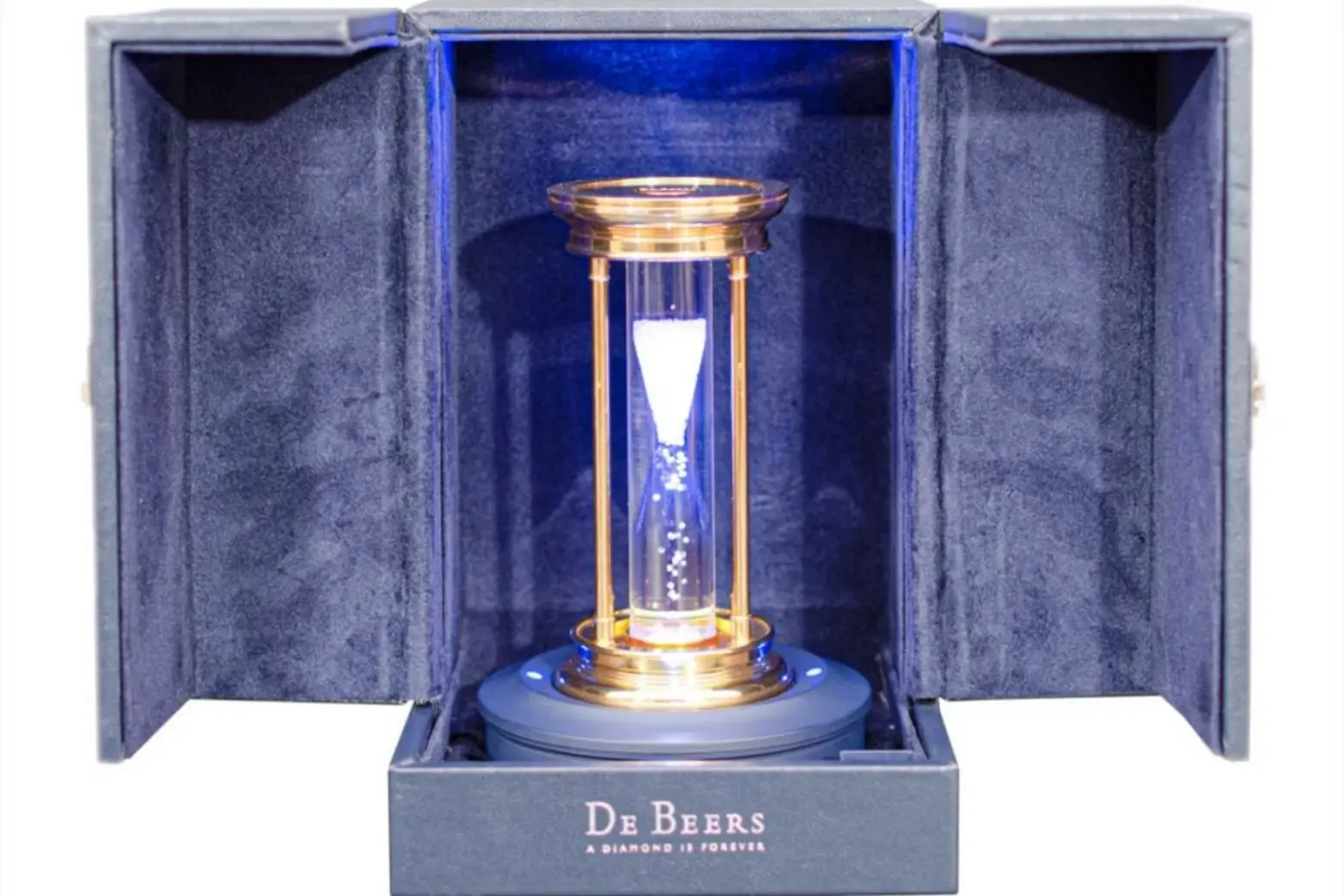

In 1947, copywriter Frances Gerety delivered the knockout blow with "A Diamond is Forever." This slogan was a strategic masterpiece disguised as a sentiment. By anchoring the stone to the concept of "forever," De Beers achieved two things. First, they gave a lump of carbon the moral weight of eternal marriage. Second, they killed the secondary market. If a diamond is forever, you never sell it. By guilt-tripping people into hoarding rings as family heirlooms, De Beers ensured that second-hand supply would never flood the market and crash their carefully managed prices.

To add a layer of "rationality" to this emotional splurge, they popularized the 4Cs: Cut, Carat, Clarity, and Color. These metrics turned the average groom into a pseudo-expert, giving him the illusion that he was making a savvy technical investment rather than succumbing to a psychological Jedi mind trick. It made a product that is notoriously difficult to value suddenly feel objective and safe.

The true legacy of De Beers isn't their mining, but their meaning prowess: Millions of people still consider a two month salary hit to be a sacred "tradition" rather than a clever 20th century PR stunt. They didn't just set the price of "happily ever after," they became the gatekeepers of it, and they’ve been collecting the interest on our collective romantic anxiety ever since.

De Beers' PR team and their colossal ad budget flew across the Pacific, landed in Japan (where tradition is famously rigid) and did the impossible: 15 centuries of traditional courtship is dismantled in a mere span of 14 years, less than it takes to raise a teenager. Between 1967 and 1981, De Beers took a country where diamonds were essentially unknown and convinced it that a sparkling rock was the only bridge to a modern, Westernized future.

The strategy was a masterclass in weaponized FOMO. By plastering ads with affluent Japanese couples yachting in high-fashion European silk, De Beers turned the diamond into the mandatory uniform for "The New Japan." They successfully framed traditional betrothal gifts - like the time-honored shuin, as dusty relics of a bygone era. If a Japanese man wanted to prove he was a progressive, world-class provider, he didn't give silk, he gave a rock that cost him a small fortune.

To really twist the knife, De Beers adjusted the "Math of Love" for the local market. While Americans were told that two months' salary was the standard for devotion, De Beers whispered to the Japanese public that three months' salary was the real benchmark for sincerity. They capitalized perfectly on the Japanese cultural emphasis on discipline and financial "seriousness," effectively convincing an entire generation that true love could be precisely calculated in ninety days of pre-tax income.

After dominating the marriage market, De Beers faced a new challenge in the early 2000s with rising divorce rates and the increasing financial independence of women. To maintain growth, they launched the "Raise Your Right Hand" campaign in 2003. This was a strategic pivot that redefined the diamond ring as a badge of female empowerment rather than a gift of male devotion. The campaign created a psychological dichotomy between the two hands. The left hand represented "we" and romance, while the right hand represented "me" and individual style. By assigning a specific personality to each hand, they ensured that buying a ring for oneself didn't compete with the tradition of an engagement ring, it supplemented it. This allowed De Beers to sell to professional women who wanted to celebrate their own career successes, successfully removing the stigma of a woman buying her own diamond.

Today, this "Self-Purchase" market is one of the fastest-growing segments in the jewelry industry. Modern campaigns like "For Me, From Me" are the direct descendants of the Right Hand Ring strategy, focusing on self-love and personal milestones.

While the "Diamond is Forever" narrative captured the heart, it was De Beers’ Central Selling Organisation (CSO) that captured the market. This "single-channel" model allowed De Beers to act as the world’s diamond regulator, meticulously leaking supply to match the demand they manufactured. By 1935, they had perfected a reinforcing loop: they used a monopoly to create artificial scarcity, which drove up the "emotional value," which in turn justified the premium prices.

However, the monopoly couldn't last forever. By the late 20th century, new mines in Russia, Australia, and Canada began bypassing the CSO, eroding De Beers’ total control. By 2000, the company pivoted from being the market's "stabilizer" to a luxury brand competitor. Yet, their greatest victory was already won: even as their market share dropped, the cultural ritual they installed remained. They proved that while you can lose control of the mines, if you control the meaning of the product, the world will still pay a premium for it.

Today, De Beers faces its greatest challenge yet: Lab-grown diamonds (LGDs). These stones are chemically, physically, and optically identical to mined diamonds but cost a fraction of the price.

Initially, De Beers resisted, launching the "Real is Rare" campaign to disparage synthetic stones. However, in a "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em" move, they launched their own lab-grown brand, Lightbox, in 2018. Interestingly, as of 2025–2026, De Beers has begun scaling back Lightbox to refocus on the "Natural is Rare" narrative, attempting to differentiate between "industrial" lab-grown stones and "miraculous" natural ones.

In the end, De Beers pulled off the ultimate "inception." They didn’t just sell a ring; they convinced the world that an 80-year-old marketing strategy was actually an ancient, sacred ritual. Today, we view the diamond engagement ring with the same biological inevitability as breathing, conveniently forgetting that before 1938, proposing with a diamond was about as "traditional" as proposing with a Bluetooth speaker.

It is the greatest trick in advertising history: rebranding a corporate monopoly’s inventory-clearing event as the "universal language of love." De Beers proved that while a diamond might be forever, a truly brilliant PR campaign is even more eternal.