The cocoon silhouette wraps the body like a timid comfort zone, soft and swaddled, yet its very volume steals the gaze with a strange, hypnotic boldness. It is open and closed at once, modest yet audacious. But here’s the tease, does the cocoon protect its wearer, or does it seduce by turning concealment itself into spectacle?

The cocoon silhouette wraps the body like a timid comfort zone, soft and swaddled, yet its very volume steals the gaze with a strange, hypnotic boldness. It is open and closed at once, modest yet audacious. But here’s the tease, does the cocoon protect its wearer, or does it seduce by turning concealment itself into spectacle?

December 12, 2025

The cocoon silhouette wraps the body like a timid comfort zone, soft and swaddled, yet its very volume steals the gaze with a strange, hypnotic boldness. It is open and closed at once, modest yet audacious. But here’s the tease, does the cocoon protect its wearer, or does it seduce by turning concealment itself into spectacle?

Fashion history is punctuated by silhouettes that did more than clothe the body, they shifted cultural perceptions, carved new ideals of femininity, and redefined elegance itself. The Cocoon silhouette belongs to this rare species. Voluminous yet tapered, architectural yet soft, protective yet daring, it has always floated between comfort and radicalism.

The first gestures belong to Paul Poiret in the 1910s, who—ever the provocateur—swaddled women in flowing oriental-inspired coats that broke free from corsetry. His cocoon coats were less about revealing the body than wrapping it, suggesting mystery instead of display. These garments, often lined in extravagant silks and brocades, resembled the protective shell of a chrysalis, hiding the body but hinting at transformation. Poiret may not have given us the cocoon dress, but he planted the seed: fashion could envelop rather than constrict, creating drama through silhouette instead of seam lines.

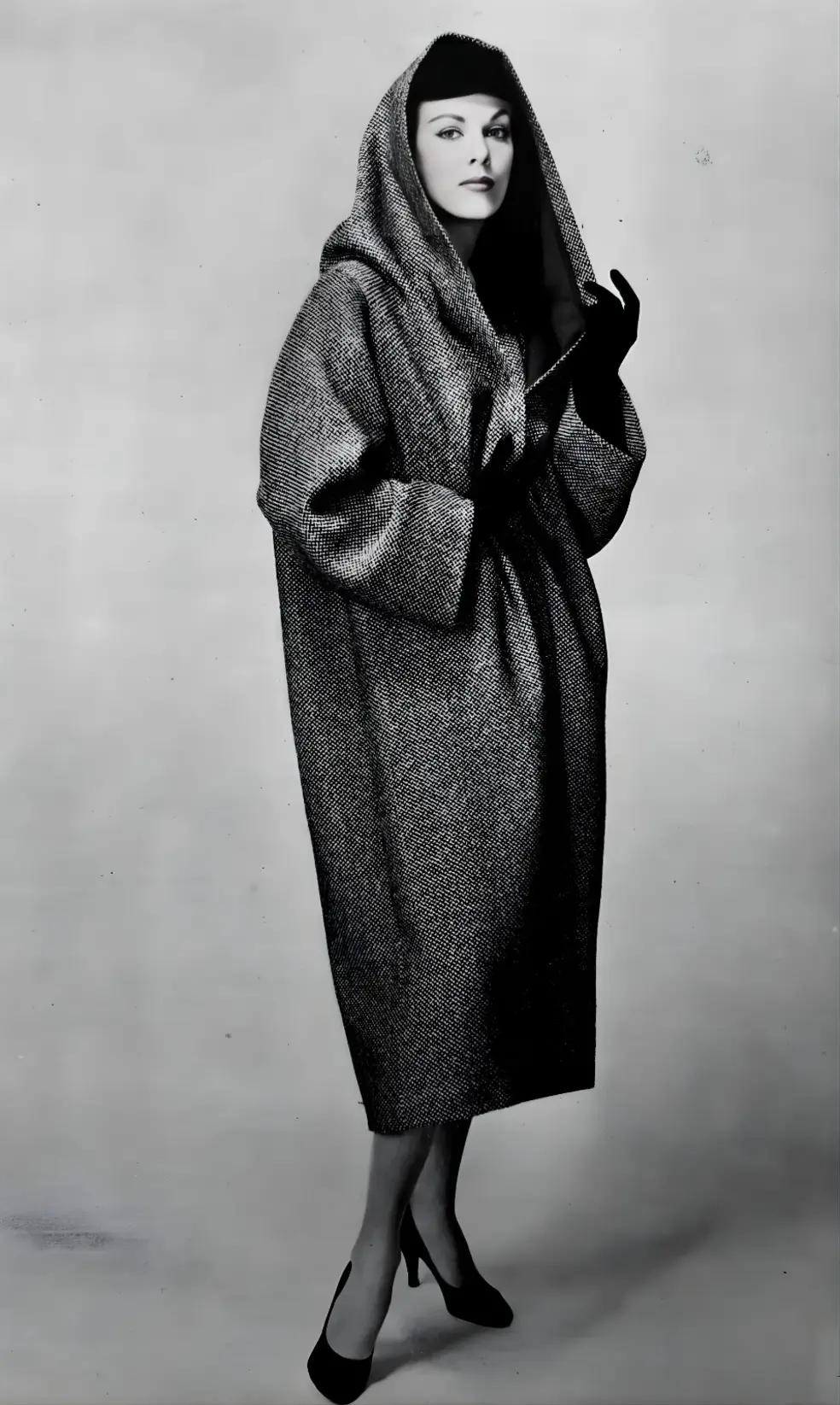

By mid-century, this seed blossomed into an unmistakable shape. In 1951, Balenciaga—Spain’s gift to Parisian couture—presented his “butterfly” silhouette, which widened at the shoulders and narrowed elegantly at the hem. The press called it radical, even confusing. By 1957, his collections had fully embraced the cocoon dress, sculptural garments cut from seemingly simple planes of fabric. Balenciaga’s genius lay not in ornamentation but in architecture: no darts, no nipped waists, no superfluous trimming. Fabric itself was enough. The result was a dress that floated away from the body, creating space between cloth and skin, liberating women from the tyranny of waistlines.

Every silhouette carries metaphor. The Cocoon is no exception. While the hourglass celebrated fertility, the column evoked classical purity, and the bell suggested grandeur, the Cocoon represented something altogether different: protection, metamorphosis, futurity.

To wear a cocoon dress was to inhabit a shell, a self-contained form that seemed to shield the wearer from external scrutiny. It carried the spirit of retreat, but also of transformation—the promise of emergence. Unlike the body-conscious silhouettes of the 1950s that demanded women conform to male-dictated ideals, the Cocoon offered autonomy. It created space for the woman, not of the woman.

Its spirit was also profoundly modern. The silhouette mirrored the streamlined futurism of mid-century design—think Eero Saarinen’s Tulip Chair or Le Corbusier’s purist curves. It was fashion in dialogue with architecture, fashion as sculpture. Minimalism became radical because it refused the ornamental.

The cocoon dress is deceptively simple, yet its simplicity conceals an extraordinary technical precision. In its purest form, it is born from two identical curved panels of fabric, dropping in a straight, unbroken sweep from head to hem. There are no darts, no tucks, no corsetry to discipline the body into shape; even the sleeves, if present, fall in a single gesture from shoulder to wrist, echoing the volume of the whole. The shoulder-to-hem curve becomes its defining gesture—broad across the top, tapering towards the knee or ankle to form the illusion of an enveloping shell. Balenciaga’s genius was to achieve volume without complication, proving that minimal seaming could produce garments that seemed to float, shaped by the cut of fabric rather than the imposition of force.

Fabric choice is crucial: silk gazar, double-faced cashmere, and sculptural wools lend the necessary body to hold structure while maintaining the elegance of drape. The back often held the element of surprise—bows, cut-outs, or subtle fitted panels that undercut the enveloping front, turning concealment into revelation. Traditionally cut to the knee, the cocoon expanded in scope through Paul Poiret’s floor-length coats and later designers’ cropped tunics and full-length chrysalides. Its beauty lies in contradiction: it barely touches the body, yet communicates formality; it conceals curves, yet radiates a strange femininity; it is minimalist in construction, yet theatrical in effect. The cocoon thrives on this paradox, a garment that performs restraint while staging drama, reminding us that the simplest shapes can often be the most radical.

Few silhouettes have proven so elastic in interpretation. The cocoon has inspired countless designers because it offers both a blank canvas and a radical stance.

The cocoon has always thrived in paradox — shy and protective on the surface, yet bold and unforgettable in its very outline. In the 1990s, it resurfaced under John Galliano at Dior, where the cocoon coat became a courtly gesture, charged with a royal aura. Galliano transformed the silhouette into something ceremonial, a garment that whispered of queens and empresses, its curves steeped in old-world grandeur but sharpened with couture excess

The 2000s reimagined that cocoon through the lens of minimalism. At Balenciaga, it appeared in stark white, stripped to its bones, futuristic in its restraint. Here, the cocoon was not about drama but about purity — a kind of architectural clarity where volume existed without ornament, an echo of Cristóbal’s original vision but translated into a new millennium’s obsession with reduction.

But at Dior 2004, the cocoon coat roared back in a different register: colorful, saturated with prints, drenched in accessories, a look that piled excess on top of excess until the silhouette itself became a crown. The cocoon engulfed the body, rising over the head, asserting its authority as a form of literal and symbolic dominance. It was power dressing at its most operatic, a fashion fortress wrapped in exuberance.

By the 2010s, the cocoon fractured into multiple identities. Mugler softened it, embracing gentle curves that cloaked the body with sensual fluidity rather than strict structure.

At the other extreme, Moschino turned the cocoon into a carnival — splashed with color, flamboyant, always on the verge of metamorphosis, like a butterfly preparing to burst from its fabric chrysalis.

Then there was Chanel, which wrapped its cocoon in luxury, bathing it in beadwork and sequins, a bejeweled chrysalis shimmering under the lights. Here, the cocoon became couture jewelry in motion, a sparkling shell that transformed modest volume into a spectacle of adornment, as if it were less a coat than a treasure chest worn on the body.

And in the background, Balenciaga, under new creative direction, brought the cocoon back into the street, layering modernity over heritage that felt both familiar and disruptive.

The 2020s, however, are where the cocoon became ferocious again. Thom Browne sharpened its edges with couture precision, slicing black and white into forms so severe they became almost architectural shrines to tailoring — making the cocoon more sophisticated than ever before.

Alexandre Vauthier approached it with Parisian chic, distilling the silhouette into sleek modern coats that cocoon the wearer with effortless glamour.

At the same time, Comme des Garçons took the cocoon into the realm of avant-garde theater, inflating it, distorting it, playing with shades of color and subversive materials until the cocoon turned mischievous, almost naughty in its rebellion against the expected.

Across these decades, the cocoon refuses to behave. It can be regal, minimal, soft, exotic, glittering, or severe, but it always commands attention because it is built on tension — open and closed, modest and audacious, shelter and spectacle. If the cocoon was once only a hushed shell, today it is fire: feisty, unstoppable, a silhouette that burns through eras by constantly reinventing what it means to be wrapped, contained, and yet more powerful than ever.

The cocoon silhouette carries the quiet aura of something shy, almost hesitant, as if it wants to retreat into its own folds, wrapping the body in a zone of comfort that feels safe and soft. Yet the very strangeness of its form—the way fabric balloons away from the body only to taper again—becomes the striking highlight that hypnotizes, memorable precisely because it is both modest and audacious, open and closed, a garment of contradictions. This dichotomy is why the cocoon refuses to fade into the background; it thrives not as a passing curiosity but as a shape that mirrors the paradoxes of our age. It shields while it reveals, it protects while it seduces, it erases the body’s contours while insisting on the presence of form. Several deeper forces have kept it in fashion’s spotlight.

At its core, the cocoon silhouette enacts a radical body neutrality. Unlike body-conscious tailoring that celebrates curves or thinness, the cocoon envelops without erasing, offering volume that neither flaunts nor shames. In doing so, it resists the long history of policing women’s figures, where every seam once dictated how the body should conform to ideals of femininity. By sidestepping the demand to highlight breasts, waists, or hips, the cocoon proposes an alternative beauty—one that rests in proportion, gesture, and movement rather than in exposure. That neutrality has proven both political and practical, resonating in eras when the body itself becomes a contested site.

Another force sustaining the cocoon’s relevance lies in sustainability. Its pared-down construction, minimal seams, and reliance on timeless geometry align with contemporary design philosophies that reject disposability. A cocoon coat or dress resists the fleeting trend cycle precisely because it does not rely on the legibility of a waistline or the currency of a particular cut. Instead, it belongs to the rare category of garments that feel outside time—abstract, sculptural, and therefore endlessly wearable. For brands increasingly pressured to prove their ecological conscience, the cocoon offers a silhouette that is simultaneously artistic and pragmatic, experimental yet enduring.

Finally, the cocoon remains a magnet for designers because it is a laboratory of ideas. Its apparent simplicity, a swollen curve narrowing into tapered hems—becomes endlessly pliable in the hands of visionaries. Balenciaga sculpted it into an architectural marvel; Rei Kawakubo twisted it into absurdist theater; contemporary designers treat it as a provocation, reinterpreting it in technical fabrics or surreal proportions. It is a form that resists closure, always open to reinvention precisely because it embodies contradiction. For every season that demands sleek tailoring or minimal lines, there is a counter-season where designers return to the cocoon, not as nostalgia but as experiment, pushing fabric into volumes that feel playful, uncanny, or even defiant.

In this sense, the cocoon silhouette is not simply a style but a statement about fashion’s ability to embody paradox. That tension is precisely why it endures—not as a relic of the past, but as one of the most intelligent, provocative shapes in the history of dress.

More than a century since Poiret first draped his women in shells of silk, the cocoon remains both mystery and manifesto. It is at once shield and stage, a silhouette that asks us to look not at the body but at the form, not at ornament but at essence.

In an industry often obsessed with novelty, the cocoon proves timeless because it is more than trend—it is philosophy. It reminds us that fashion can be both armor and art, protection and provocation.

And perhaps that is why, season after season, the cocoon returns. Like the butterfly it echoes, it never really disappears. It waits, quietly, until fashion is once again ready for transformation.