Kryptos, the copper-and-stone sculpture Jim Sanborn installed in the CIA courtyard on November 3, 1990, became famous not just for hiding four encrypted passages but for the long, public race to crack them.

Kryptos, the copper-and-stone sculpture Jim Sanborn installed in the CIA courtyard on November 3, 1990, became famous not just for hiding four encrypted passages but for the long, public race to crack them.

October 30, 2025

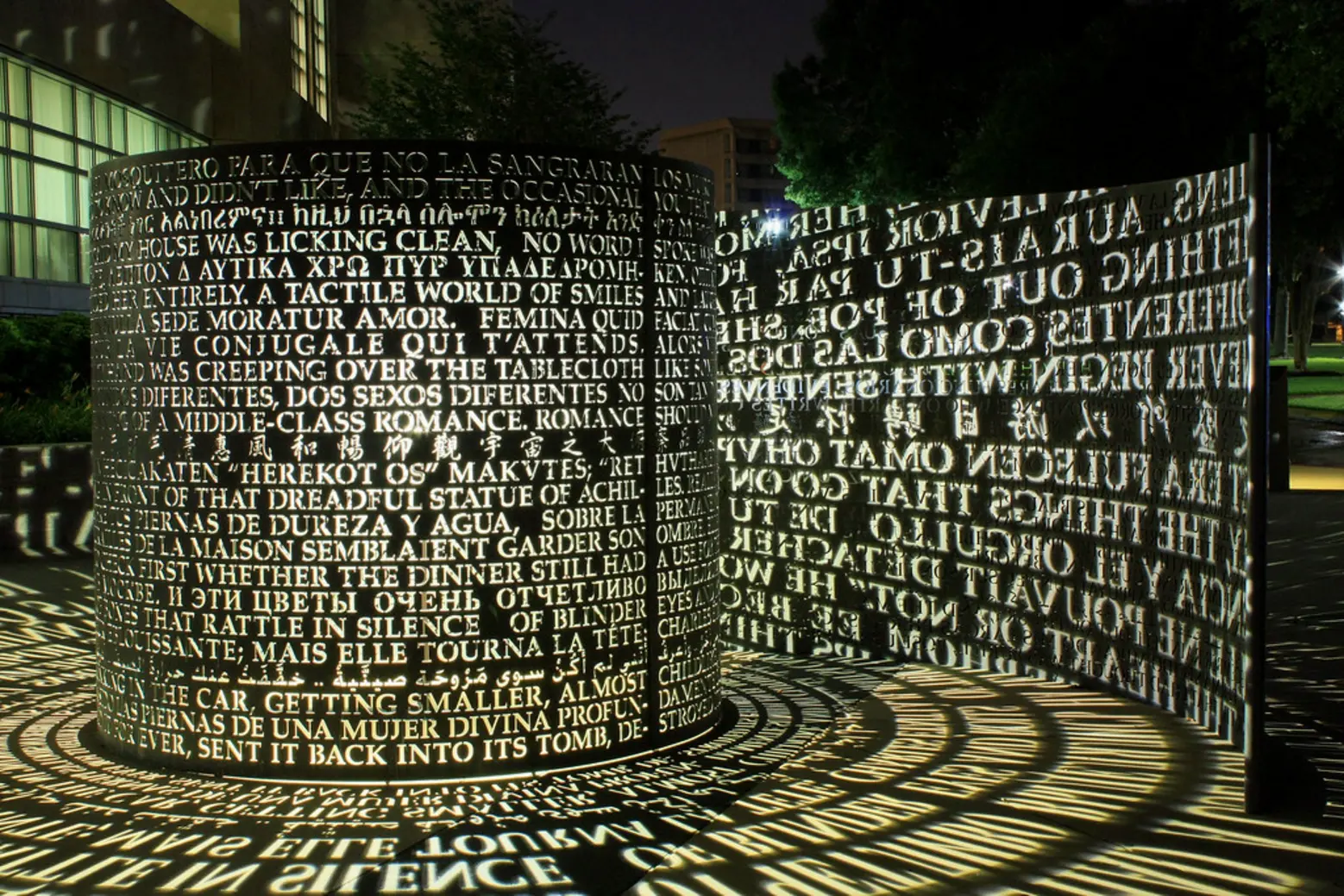

The sculpture is built from four large copper panels and is surrounded by other elements, including water, wood, plants, red and green granite, white quartz, and even petrified wood. The centerpiece is a tall, S-shaped copper screen that looks like a scroll or a sheet of paper feeding out of a computer printer with about half of its surface covered in encrypted text.

For nearly a decade no one outside the intelligence world claimed success. That changed in 1999 when Jim Gillogly, a computer scientist from southern California, announced that he had deciphered the first three parts with the help of a computer. Shortly afterward the CIA confirmed that its own analyst, David Stein, had actually solved the same passages in 1998 using pencil-and-paper methods, though his work had circulated only inside the agency until July 1999. Both efforts showed that Sanborn’s sculpture could be attacked from different directions.

For years solvers believed that the second passage ended with the clumsy plaintext “WESTIDBYROWS.” In 2005 Canadian logician Nicole Friedrich pointed out that the letters could instead read “WESTXLAYERTWO.” On April 19, 2006, Sanborn told the online Kryptos community that he had made a lettering error on the sculpture—an omitted S in the ciphertext—and confirmed that “WESTXLAYERTWO” was the real ending, resolving a long-running ambiguity.

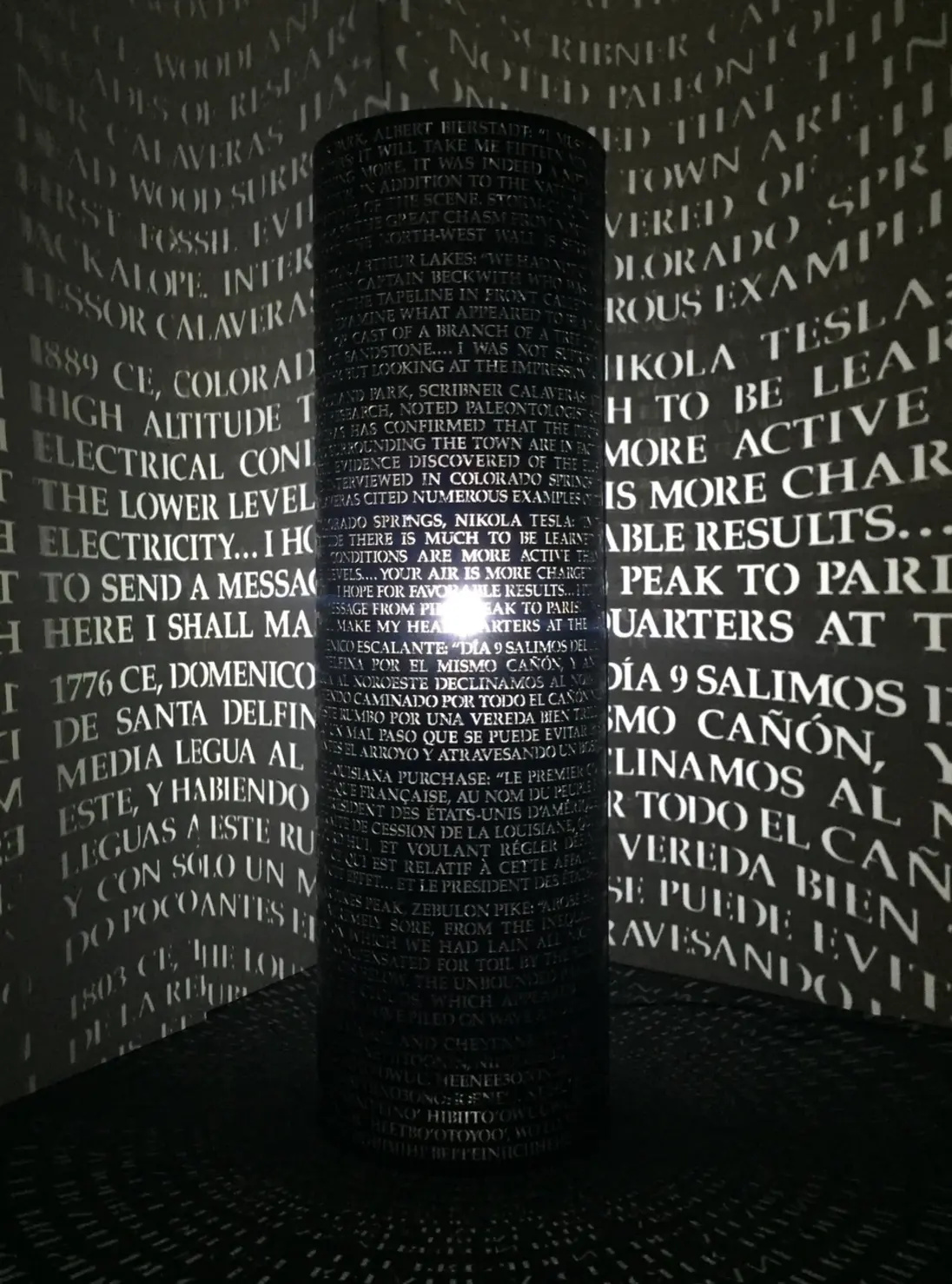

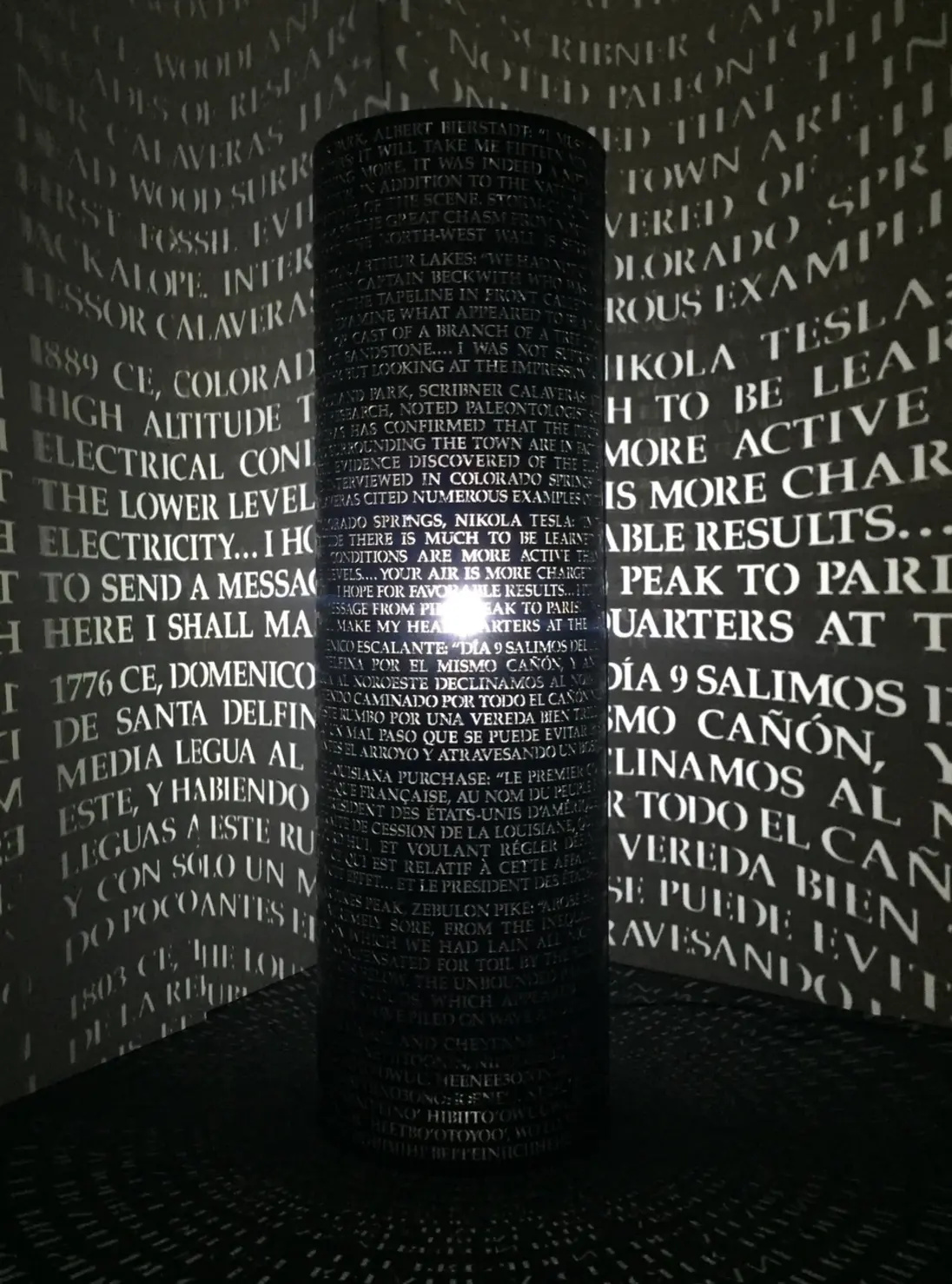

Kryptos sparked a small universe of related work. Sanborn later produced coded pieces such as the Untitled Kryptos Piece, Cyrillic Projector, and the 1997 sculpture Antipodes, which repeats part of the Langley text with slight differences. Popular culture noticed too: Dan Brown hid references in The Da Vinci Code and revisited them in The Lost Symbol, Alias built a gag around a quick solution and Netflix’s The Recruit nodded to it with “Kryptos Donuts.” The final section, K4, still waits for a solution.