On November 1, 1512 — All Saints’ Day, Rome looked up and gasped. As the chapel of the Apostolic Palace filled with clergy and courtiers, the veil of scaffolding finally fell from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, revealing a cosmos of painted stone that seemed to breathe.

On November 1, 1512 — All Saints’ Day, Rome looked up and gasped. As the chapel of the Apostolic Palace filled with clergy and courtiers, the veil of scaffolding finally fell from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, revealing a cosmos of painted stone that seemed to breathe.

November 1, 2025

Four years earlier, Pope Julius II had pressed a reluctant Michelangelo, then famed chiefly as a sculptor, into the risky, back-breaking task of frescoing the chapel’s barrel vault. What opened to the public that morning was not mere decoration but a new grammar for Western art.

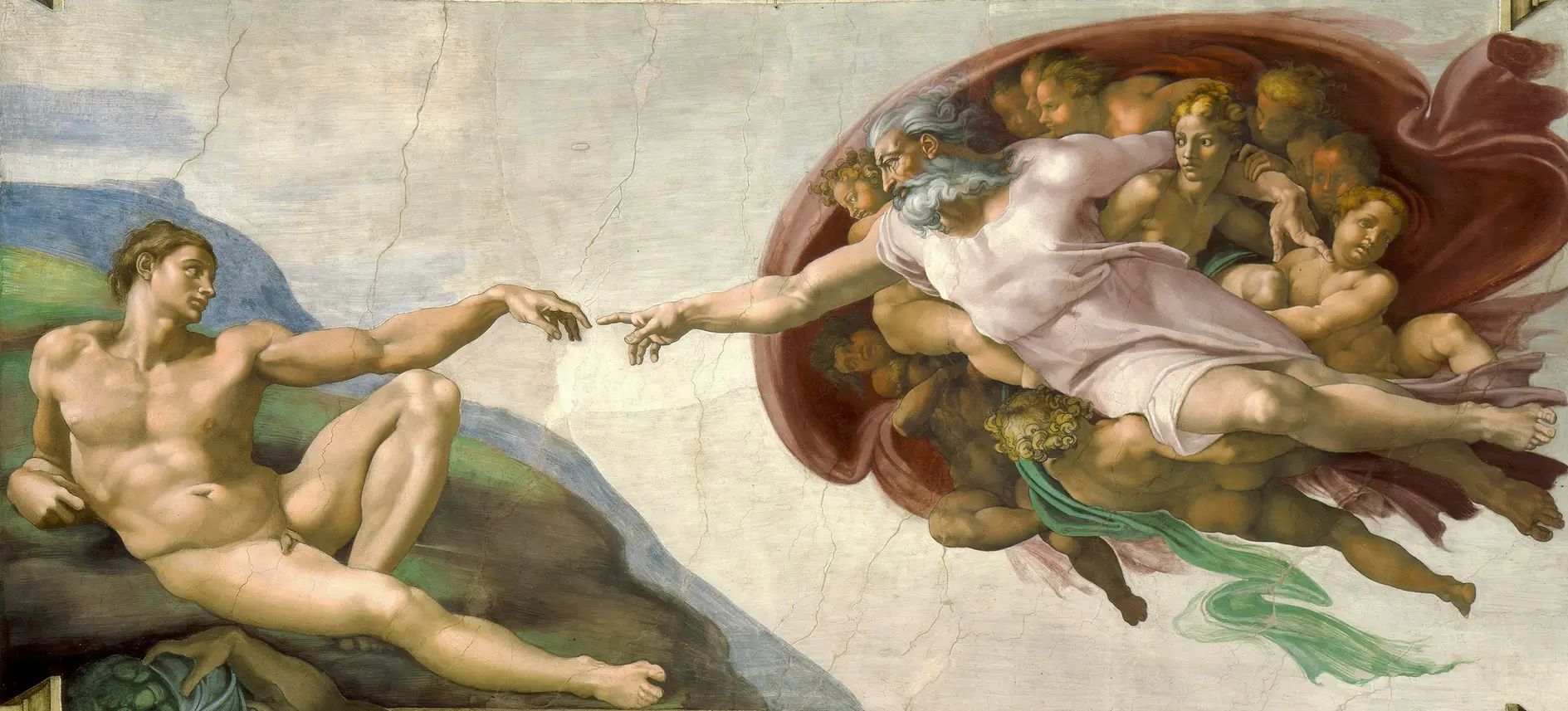

The vast ceiling unspools like an epic poem in paint. In the nine central narratives, from the Separation of Light from Darkness to the Creation of Adam and the Drunkenness of Noah, Michelangelo stages the Book of Genesis as theater: muscular figures stride, twist, and hover with a sculptor’s weight and a poet’s cadence.

Around them, colossal Prophets and Sibyls — Hebrew seers and pagan visionaries, sit enthroned within illusionistic architecture, their attendant youths (ignudi) looping garlands and bronze medallions that are not bronze at all but paint carried to the edge of disbelief. Nearly three hundred figures knit into a framework of fictive cornices and pilasters, turning a modestly proportioned room into an inexhaustible universe.

That first unveiling was as much technological triumph as spiritual spectacle. Fresco demands speed and certainty — pigment driven into wet plaster before it dries, and Michelangelo mastered it at monumental scale, designing custom scaffolding, painting in two campaigns, and revising his own approach as he went. The color, once dulled by centuries of candle soot, originally blazed: apple greens, lapis blues, and coral pinks that made bodies read at a distance yet bloom in close view.

The impact was immediate and seismic. Artists flocked to measure its foreshortenings and steal its secrets of anatomy; patrons recalibrated their ambitions; Rome, already the stage of antiquity, became the academy of the modern. Yet the ceiling’s miracle is not only virtuosity, but vision: a drama of creation that marries divine spark to human potential. On that November day, the chapel did not simply gain a ceiling. It gained a sky—and art history found a new horizon.