Behind every fierce heel and iconic hem lies a story of ambition, ego, and very expensive thread. These fashion films reveal how cinema turns clothing into character, culture, and mythology.

Behind every fierce heel and iconic hem lies a story of ambition, ego, and very expensive thread. These fashion films reveal how cinema turns clothing into character, culture, and mythology.

September 24, 2025

Fashion is not only about fabric, fit, and finish; it is about memory, myth, and meaning. Few art forms capture this interplay as vividly as cinema. A dress on screen can be more than a costume. It can be character, culture, even revolution. Over the decades, films have become fashion bibles, not through glossy stills alone, but through narrative power, emotion, and the ineffable way that clothes move when a character breathes life into them.

Here are eleven films that reveal fashion’s paradoxes: its glamour and absurdity, its artistry and its commerce, its eternal hunger to reinvent, and its inability to escape its own reflection.

Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter is not a love letter to fashion, but a satirical postcard. Shot in Paris, it is a kaleidoscope of chaos, a week-long romp through Fashion Week that reveals an industry intoxicated by its own image. There are editors jostling for seats, designers flouncing backstage, and a ludicrous final runway in which models march naked - a metaphor as subtle as a feather boa, yet unforgettable.

Altman’s genius was not in flattering fashion but in puncturing its balloon. He showed how the industry, with its obsession with status and spectacle, often teeters on the edge of parody. And yet, beneath the laughter, there is truth: fashion is theatre, and the runway is its stage. The film reminds us that fashion is not just about beauty; it is also about absurdity, ego, and excess.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread is the antithesis of Altman’s chaos. It is slow, meticulous, and suffused with dread - a meditation on obsession. Daniel Day-Lewis’s Reynolds Woodcock, a fictional couturier in 1950s London, is the embodiment of couture’s beauty and cruelty: a man who can coax silk into poetry, but who tyrannises the women around him.

The film captures couture’s rituals: hand-stitching hems, measuring models with forensic precision, the silence of the atelier punctuated only by the snip of scissors. Yet Anderson is honest about the price of genius. Beauty here is not benign; it is suffocating, controlling, and, at times, destructive. Watching Phantom Thread is like slipping into a gown woven of silk and thorns. Exquisitely, but impossible to forget.

Few documentaries have captured the balance of power and creativity as precisely as The September Issue. Directed by R.J. Cutler opens the doors of Vogue during the making of its legendary September 2007 edition, which is the thickest, glossiest, most influential issue in magazine history.

At its heart is the battle, or dance, between Anna Wintour, the imperious editor-in-chief, and Grace Coddington, the visionary creative director. Wintour is steel in sunglasses; Coddington is fire in flowing red hair. Their clashes, compromises, and creative triumphs reveal an industry where commerce and creativity are perpetually at odds.

What makes the film iconic is not just its access but its honesty. It shows fashion as empire: powerful, flawed, indispensable. For anyone who has ever wondered how an image can ripple across the globe and dictate what women wear, The September Issue is the answer.

If Phantom Thread is fiction, Valentino: The Last Emperor is its elegiac reality. Directed by Matt Tyrnauer, the documentary follows Valentino Garavani through his final years at the helm of his house, culminating in his spectacular 45th anniversary show in Rome.

What we see is not just gowns. Though they are breathtaking in their chiffon clouds and crimson cascades, but the machinery of haute couture. The seamstresses whose hands make magic. The partner, Giancarlo Giammetti, who steadies Valentino’s temper and vision. And the looming shadow of corporate ownership, as the house is sold to private equity.

It is a love story: between designer and craft, between Valentino and Giancarlo, but also a lament. A world where beauty reigned supreme is fading, overtaken by spreadsheets and shareholders. The emperor takes his final bow, and with him, a chapter closes.

Before she became a legend, Gabrielle Chanel was a misfit. Coco Before Chanel, starring Audrey Tautou, is less a biopic than a parable of rebellion. It contrasts the frills and corsets of Belle Époque society with Chanel’s austere vision: comfort, line, and liberation.

The film captures Chanel’s refusal to conform: her rejection of ornament, her insistence on simplicity, her creation of androgynous chic long before the word existed. Watching Tautou stalk through salons in crisp white shirts and boyish hats, one realises that Chanel’s revolution was not aesthetic alone but cultural. She unshackled women from clothing that constrained, offering garments that liberated. Fashion, in her hands, became not costume but freedom.

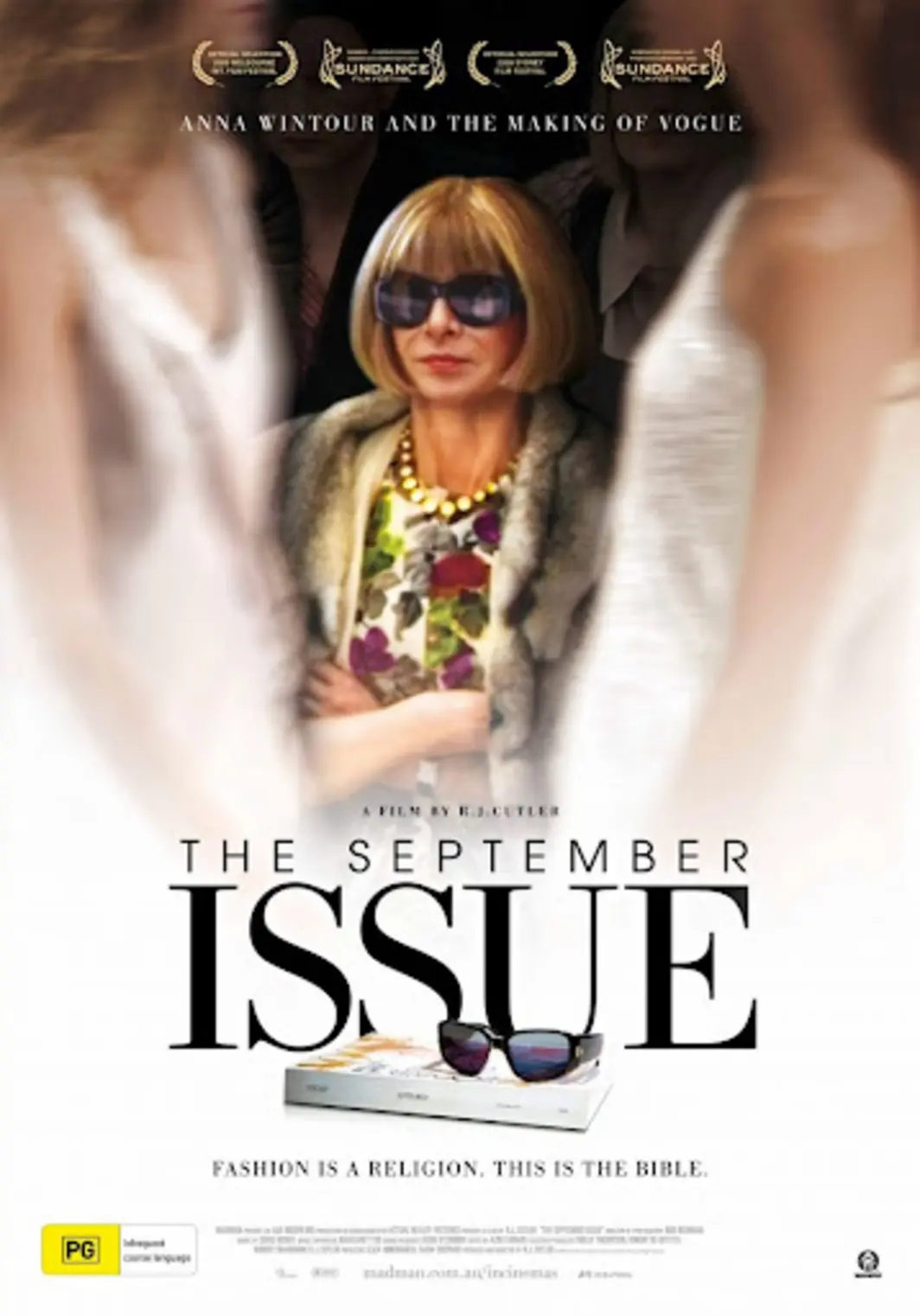

It is tempting to dismiss The Devil Wears Pradaas froth, but that would be to underestimate its power. Meryl Streep’s Miranda Priestly is a caricature, yes, but one rooted in reality. Editors who dictate taste with a raised eyebrow do exist, and they shape industries and careers with terrifying efficiency.

The film is a parable of power, ambition, and the compromises demanded by fashion’s rarefied world. Anne Hathaway’s Andrea evolves from sloppy intern to sleek insider, her wardrobe charting her transformation as surely as any dialogue. Valentino, Chanel, and Jimmy Choo parade across the screen, but the true subject is identity: what we lose and what we gain when we enter fashion’s gilded cage.

No designer embodied the extremes of beauty and brutality like Alexander McQueen, and no documentary has captured his contradictions as poignantly as McQueen. Directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, it is a mosaic of archive footage, runway shows, and personal testimonies that reveal a man who turned trauma into theatre.

McQueen’s shows were not mere presentations. They were spectacles that blurred art, performance, and nightmares. Models walked through glass boxes of moths, down runways lined with fire, or became cyborgs sprayed by robots. Behind this genius was pain: personal, psychological, and ultimately unbearable.

The film is not an easy watch. But it is essential. It shows that fashion, at its most powerful, can be as devastating as it is dazzling.

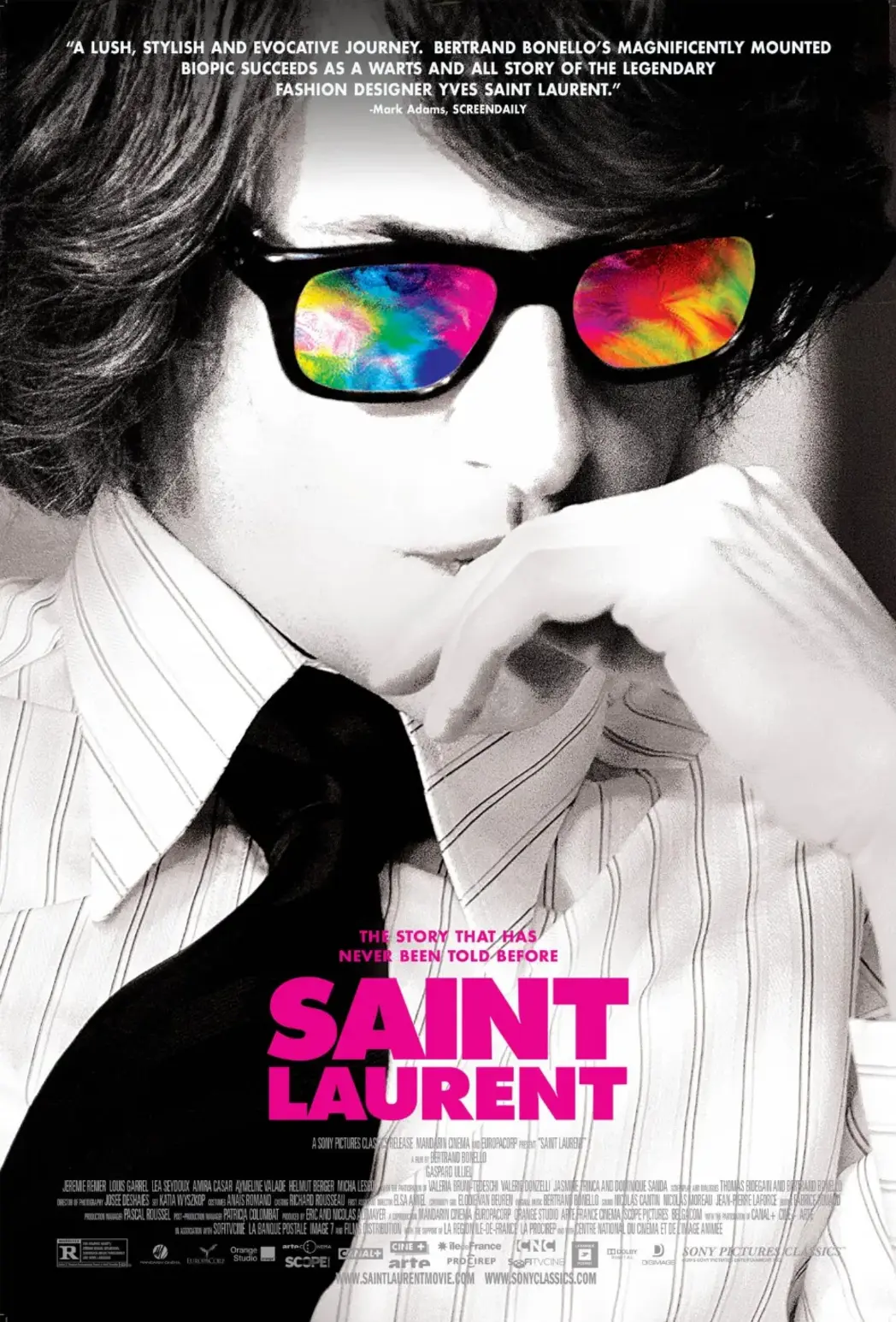

Jalil Lespert’s Yves Saint Laurent is not the definitive film on the designer, but it is a compelling portrait of fragility wrapped in brilliance. Pierre Niney embodies YSL as a man whose radical creativity, from the Mondrian dress to Le Smoking tuxedo that reshaped women’s wardrobes. However, his personal life was haunted by addiction and insecurity.

The film captures the paradox of Saint Laurent: a visionary who gave women power through clothes, yet who struggled to control his own demons. Suzy might note the melancholy: genius rarely comes without cost.

Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci is as operatic as its subject: a dynasty undone by ambition, betrayal, and murder. Lady Gaga chews scenery in vintage Gucci power suits, Adam Driver broods, and Al Pacino declaims. It is camp, yes, but also cautionary.

The fashion is meticulously curated: bamboo-handle bags, silk scarves, double-G belts. But beneath the glamour lies a truth: luxury is fragile. It is built not only on leather and logos but on family, trust, and legacy. When those crumble, even an empire as mighty as Gucci can falter.

While other films revel in excess, Bill Cunningham New York is about humility. Cunningham, the bicycle-riding photographer for The New York Times, documented fashion not on catwalks but on sidewalks. His lens found poetry in a passerby’s coat, humour in a hat, dignity in a uniform.

The film is a love letter to a man who believed fashion belonged to everyone, not just the elite. Cunningham’s modesty was radical in an industry addicted to ego. His eye was sharp, his heart open. He reminds us that fashion, at its best, is democratic.

Douglas Keeve’s Unzipped is camp, chaotic, and utterly delightful. It follows designer Isaac Mizrahi as he prepares his fall 1994 collection, with cameos from Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, and Linda Evangelista. Mizrahi is witty, neurotic, and endlessly entertaining - a reminder that fashion, for all its drama, can also be joyous.

The film captures the madness of show preparation, the sting of criticism, and the sheer thrill of creation. It is fashion as comedy, and comedy as truth.

What unites these twelve films is not their glamour alone but their candour. They show fashion as empire, as art, as folly, as love. They remind us that clothes are not just fabric, but narrative - threads that bind us to culture, memory, and meaning.

Cinema, like couture, is a mirror. These fashion films reveal not only how we dress, but who we are.