From orphaned beginnings to global couture domination, Coco Chanel rewrote the rules of fashion. Her genius lay not merely in creating garments but in transforming women’s relationship with style, comfort, and freedom. She made minimalism revolutionary, and elegance eternal.

From orphaned beginnings to global couture domination, Coco Chanel rewrote the rules of fashion. Her genius lay not merely in creating garments but in transforming women’s relationship with style, comfort, and freedom. She made minimalism revolutionary, and elegance eternal.

September 24, 2025

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel, universally known as Coco, emerged from hardship with a story almost as meticulously crafted as her designs. Orphaned at a young age and raised in a convent at Aubazine, she learned discipline, order, and sewing — tools that would later shape her revolutionary vision. Yet she never allowed her early life to define her. Instead, she wove it into myth, embellishing and elevating her narrative until it became inseparable from the legend of Chanel. The nickname “Coco,” born from a café song she performed to survive, would become shorthand for audacity, innovation, and style.

Her early experiences instilled in her a profound understanding of the constraints placed on women — both physically and socially — and a belief that clothing should empower, not restrict. This philosophy would inform every stitch of her work, guiding her as she began to navigate the world of Parisian fashion, then dominated by elaborate, cumbersome garments that prioritized display over comfort. The austere beauty of her childhood — the quiet rhythms of convent life, the precise lines of the stitching she learned — would later infuse her designs with a subtle intelligence that married functionality and elegance.

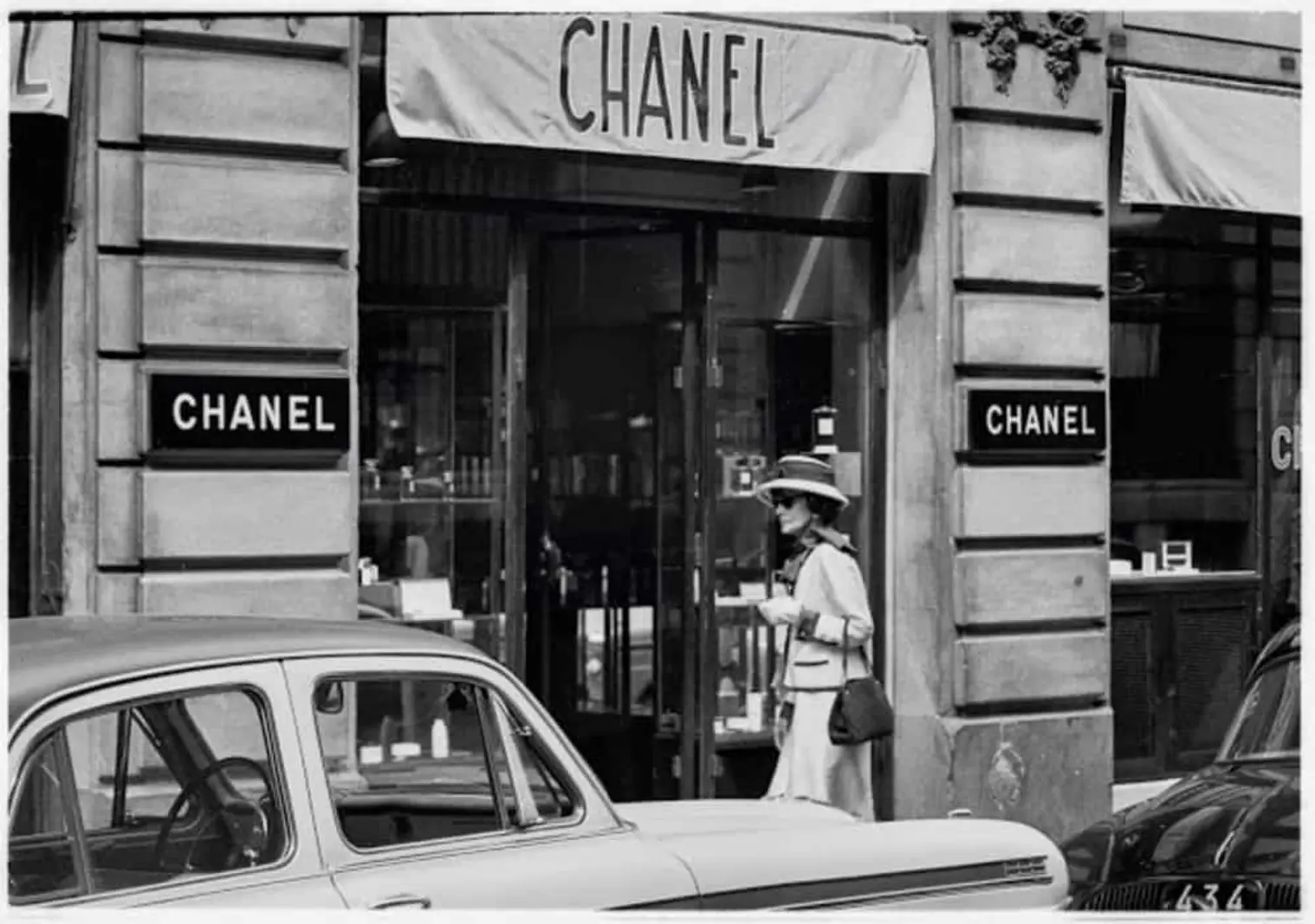

In 1910, Chanel opened her first shop, Chanel Modes, at 21 Rue Cambon in Paris. At a time when hats soared high with feathers, velvet, and lace, Chanel stripped away the excess. Her designs were small, elegant, and practical. These deceptively simple hats set the tone for a career built on understatement: a belief that function could be as beautiful as ornament, and that elegance could exist without spectacle.

The success of her hats reflected more than aesthetic taste; it was a statement of intelligence and foresight. Women who had previously been constrained by the rigid fashions of the Belle Époque found freedom in her designs. The hats were wearable, refined, and adaptable, offering a quiet rebellion against the ornamental excess that dominated Parisian society. They were a declaration that chic could be practical and that fashion could respect the wearer’s life rather than dominate it.

By 1913, Chanel had begun to transform the very fabric of women’s wardrobes. In Deauville, she borrowed a simple jersey sweater from her lover Boy Capel and reshaped it into dresses and suits that allowed women unprecedented ease of movement. Jersey, previously dismissed as cheap and shapeless, became a vehicle for both practicality and elegance. In a society that prized visible display over comfort, Chanel’s genius was to recognize that freedom and style need not be mutually exclusive. Her garments liberated women physically, allowing them to navigate work, leisure, and society with dignity and ease.

Building on this philosophy, she introduced the Little Black Dress. Black, once reserved for mourning, was transformed into a color of empowerment. The LBD was minimalist, versatile, and accessible — its elegance available to women across classes and occasions. Vogue famously dubbed it “the Ford of fashion,” underscoring its ubiquity and democratizing influence. Together, jersey and the LBD exemplified Chanel’s vision: clothing should enable movement, express individuality, and maintain grace. These innovations were as much philosophical as sartorial; they challenged the social codes of femininity, granting women autonomy over their own bodies and appearance. In essence, Chanel was not merely creating fashion — she was redefining the female experience itself, proving that clothing could serve as a conduit for independence and modernity.

Her designs were met with both admiration and resistance. Traditionalists decried the practicality and simplicity of her work, viewing it as an affront to the ornate traditions of Parisian couture. Yet women immediately recognized the liberation her pieces offered. They were elegant without artifice, stylish without discomfort, and above all, they allowed women to inhabit their lives fully and without constraint.

Chanel’s genius extended beyond dresses. Inspired by trips to Scotland with Boy Capel, she discovered tweed — a fabric associated with masculinity and the countryside — and transformed it for women. The Chanel jacket, cropped, collarless, and edged with braid, combined structure with ease, offering mobility without sacrificing elegance. The interplay of masculine material and feminine tailoring was itself a quiet act of rebellion, challenging conventions of gender and refinement.

When Chanel reopened her house in 1954, tweed had become more than material; it was a symbol of refinement, sophistication, and female autonomy. It reflected a continuity in her vision: clothing that was both functional and aspirational, practical yet exquisite. Public and critical reception confirmed Chanel’s cultural authority: tweed was no longer merely a countryside textile; under her hand, it became a timeless icon of empowerment and elegance, bridging comfort, freedom, and style.

Where contemporaries shouted — Schiaparelli with surrealism, Dior with opulence — Chanel whispered through clean lines, neutral hues, and subtle sophistication. Her clothes did not demand attention; they invited it. Fashion became a servant, not a tyrant, a tool of empowerment rather than ornamentation.

Her own persona mirrored her creations: pearls, tailored suits, understated makeup, and an aura of controlled mystique. Chanel borrowed from men’s wardrobes, challenged gender norms, and understood the power of narrative as intimately as she understood fabric and cut. Every accessory, every jacket, every sheath dress carried her intelligence — a reminder that elegance and modernity could coexist without compromise.

Chanel’s subtle radicalism was not only aesthetic but social. She reshaped expectations for women’s comportment, enabling confidence and authority through dress. Her innovation lay in seeing freedom where others saw limitation, in turning simplicity into revolutionary expression, and in proving that practical elegance could itself be aspirational.

Chanel’s influence is everywhere: in tweed jackets, little black dresses, and garments that balance comfort with elegance. Her legacy is not only sartorial but philosophical: fashion can liberate, simplicity can be revolutionary, and elegance can be both attainable and timeless. Coco Chanel did not merely design clothes; she designed freedom, reshaping the lives of women everywhere and leaving a blueprint for modernity that endures.

Her work remains a testament to the power of intellect applied to craft, of elegance intertwined with utility, and of vision harmonized with practicality. In every carefully cut jacket, every understated dress, and every pearl necklace, Chanel’s spirit endures — a quiet yet unstoppable force reminding women that style, freedom, and confidence are inseparable.