Was Dior’s New Look a liberation of femininity or a return to restrictive ideals? Its cinched waists, billowing skirts, and staggering use of 25–40 yards of fabric per dress provoked both admiration and controversy. In 1947, Paris reclaimed its fashion crown, yet Dior’s audacious debut stitched drama, politics, and fantasy into every seam.

Was Dior’s New Look a liberation of femininity or a return to restrictive ideals? Its cinched waists, billowing skirts, and staggering use of 25–40 yards of fabric per dress provoked both admiration and controversy. In 1947, Paris reclaimed its fashion crown, yet Dior’s audacious debut stitched drama, politics, and fantasy into every seam.

September 17, 2025

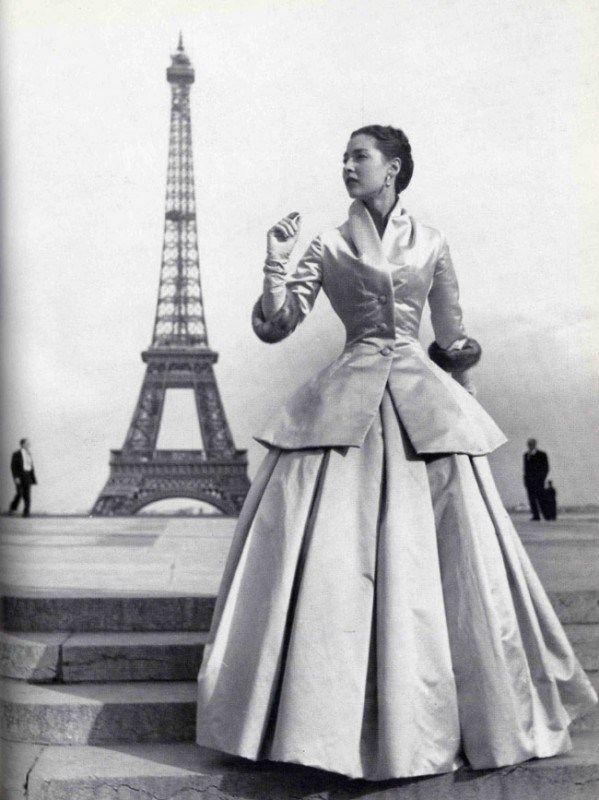

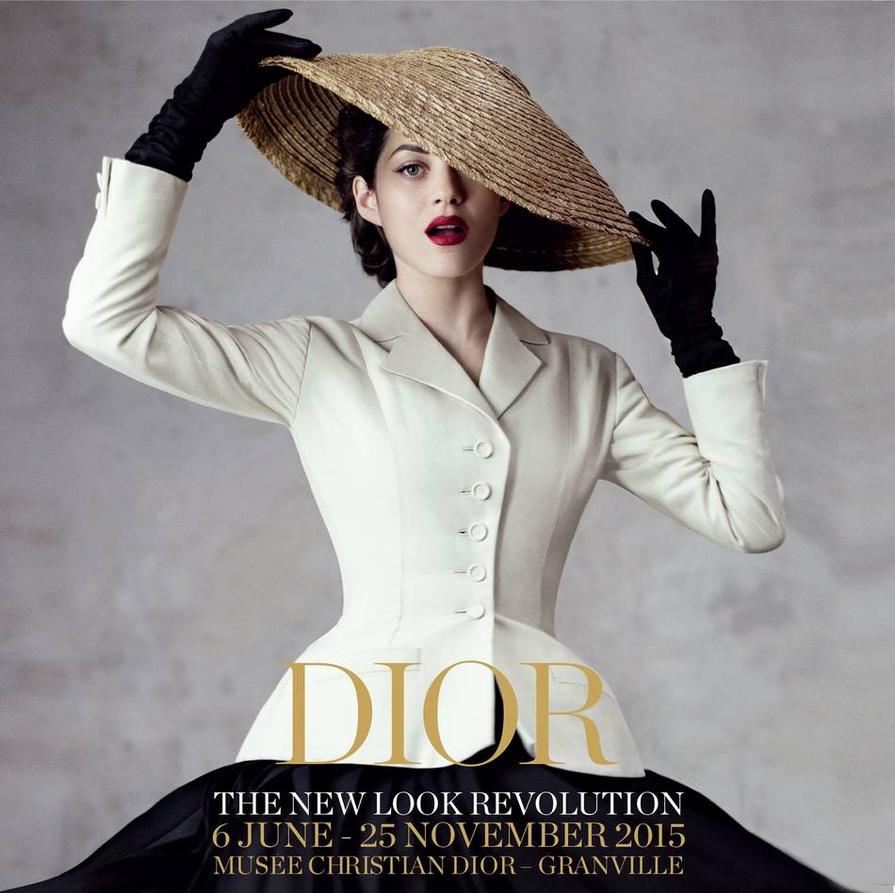

In the immediate postwar years, Parisian couture demanded drama, symbolism, and spectacle. Dior’s debut was not merely clothing—it was theatre, architecture, and cultural commentary woven in fabric. The New Look, unveiled on February 12, 1947, amid Paris’s lingering winter chill, heralded the rebirth of French couture after the devastation of the German occupation. Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase recalled the collection’s “fairly romantic flavor” and its ability to make women feel “charmingly costumed.” Dior’s silhouettes—soft shoulders, rounded busts, cinched waists, and voluminous skirts—signaled a dramatic return to ornamental femininity.

Yet this revival of extravagance carried a sharp edge: each skirt required 25 to 40 yards of fabric, a volume that provoked murmurs of disbelief across a Europe still rationing and rebuilding. To some, it was an almost scandalous display of opulence; to others, it was the triumphant statement of couture’s revival, asserting that elegance could survive even amid scarcity. Dior’s New Look became a lightning rod for discussion, simultaneously enchanting, empowering, and provoking.

In December 1946—a mere two years after Paris’s Liberation—Christian Dior inaugurated his maison de couture with the backing of textile magnate Marcel “King of Cotton” Boussac. His immediate success stemmed from the audacious New Look silhouette. Dior opposed the wartime straight lines and boxy shapes, replacing them with soft shoulders, rounded busts, cinched waists, and voluminous skirts that could require prodigious quantities of fabric.

As Dior reflected in his autobiography:

By daring to employ 25 to 40 yards of fabric per skirt, Dior’s designs were a direct challenge to the austerity of the moment. They were luxurious, theatrical, and inevitably controversial—a bold assertion that French couture was not merely surviving but asserting its postwar supremacy.

Bettina Ballard, Vogue’s fashion editor at the time, recounted the unprecedented spectacle:

The staggering volume of fabric was impossible to ignore. With 25 to 40 yards required per skirt, Dior’s New Look confronted a postwar audience still coping with rationing and material shortages. The controversy amplified the collection’s impact, transforming it into both a triumph and a provocation.

, observed its youthfulness and accessibility:

Yet the sheer scale of material used sparked debate. Critics questioned the morality of extravagant skirts in a time when fabric was scarce, while admirers celebrated the designs as a declaration of optimism and postwar resurgence. Dior’s creations symbolized hope, refinement, and fantasy—a phoenix rising from wartime austerity. Designer Valentina, a client of the house, reflected:

By demanding 25 to 40 yards of fabric per skirt, Dior simultaneously challenged norms, provoked moral debate, and defined postwar luxury. The New Look became a symbol of resilience and audacity—a reminder that fashion is never neutral. It is art, politics, and spectacle, sewn together with threads of both controversy and admiration.

Dior’s New Look was revolutionary yet nostalgic, a postwar silhouette both aspirational and theatrical, blurring the line between practicality and fantasy. Its extravagant fabric consumption provoked discussion not only among the press but also within households and boutiques across Europe and America.

The New Look’s legacy persists today. Its voluminous skirts, cinched waists, and deliberate use of fabric established a blueprint for postwar femininity, influencing designers from Balenciaga to modern haute couture. Its paradox—luxury versus scarcity, liberation versus constraint—remains a study in how fashion can embody cultural tensions while enchanting the public imagination.

Dior’s audacity demonstrated that couture could thrive not only as clothing but as theatre, architecture, and cultural storytelling. Even decades later, the memory of 25–40 yards of fabric per skirt reminds us that fashion can provoke, inspire, and define an era—sometimes all at once.