From couture cathedrals to red-carpet moments, the X-line silhouette remains fashion’s ultimate statement of power, beauty, and poise.

From couture cathedrals to red-carpet moments, the X-line silhouette remains fashion’s ultimate statement of power, beauty, and poise.

October 2, 2025

The X-line silhouette is fashion’s ultimate stage direction: waist, take a bow; skirt, make an entrance. No other line so brazenly commands the room. When it appears, whether on a couture runway or a red carpet, it transforms the wearer into an event.

At Dior 25, Maria Grazia Chiuri didn’t simply reference the house’s DNA — she revived it with precision. Skirts flared in disciplined arcs, recalling Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look yet charged with 2025 relevance. It was a collection that reminded the world that Dior invented this silhouette not as nostalgia, but as a cultural declaration: we are alive, and we will be beautiful.

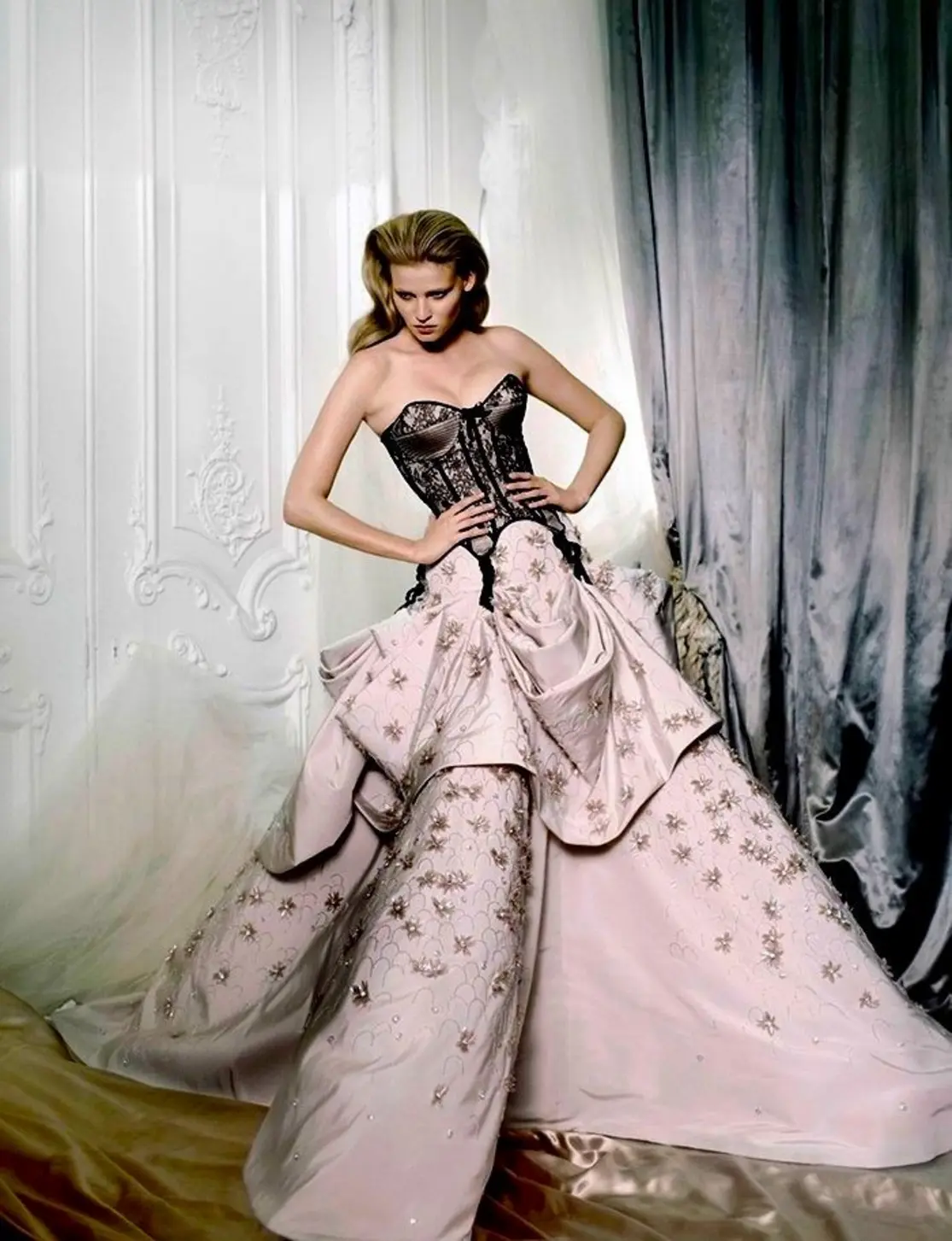

Elie Saab turned the X-line into a celestial phenomenon. His corseted gowns glittered like galaxies, skirts blooming with crystal constellations that swept across the runway like comets.

Zuhair Murad, always the master of seduction, brought the X-line into midnight territory — his waists framed in embroidery like jewels, skirts slit daringly high, hips swathed in transparent lace.

Armani Privé took a different route: precise tailoring, shoulders squared, waists architectural, skirts flaring with measured restraint. It was an X-line for queens, not princesses — power over romance.

Oscar de la Renta countered with a whisper of spring, floral appliqués crawling across gowns, waists delicate but present, skirts soft enough to catch in a breeze.

And Daniel Roseberry at Schiaparelli made the X-line sculptural: gilded corsetry, bustiers shaped like breastplates, skirts that swirled like surrealist brushstrokes — more art gallery than ballroom.

The theatre of couture proves the X-line is not simply a cut — it is spectacle. It is the architecture of attention.

To understand why the X-line holds this much power, one must rewind to 1947. Christian Dior’s debut collection — quickly dubbed the “New Look” — was not merely a fashion show. It was a cultural detonation. Postwar Paris was a city still licking its wounds: women had spent years in rationed uniforms, shoulders squared like soldiers, skirts shortened out of necessity. Fabric was a rationed commodity, femininity had been functionalized.

Then Dior swept away the austerity with wasp waists, rounded shoulders, and skirts that devoured yards of fabric. Governments protested that the waste was indecent. Women, however, saw salvation. The X-line was not just a design — it was permission to be extravagant again, to celebrate their bodies, to feel softness after years of hardness. It was a resurrection stitched in silk.

The X-line differs from its sister silhouettes — the A-line, H-line, Y-line — because it is both balance and tension. The shoulders and hem mirror each other, meeting at the waist, which becomes the axis of the entire look. It is fashion’s most perfect equation: widen, cinch, widen again.

This is not just mathematics but theatre. The eye follows the line naturally: shoulders to waist, waist to skirt, creating a rhythm that is deeply satisfying. To wear an X-line dress is to wear harmony — and harmony is seductive.

Grace Kelly turned the X-line into Hollywood’s purest emblem of elegance, her cinched waist and blooming skirts sculpting beauty into timeless proportion.

From Rear Window’s chiffon masterpiece to her royal wedding gown, she proved the silhouette could reign on screen and in history.

The X-line was a direct answer to the psychological hunger of its era. After years of war, scarcity, and functional clothing, women were ready for beauty. The yards of fabric in those first skirts were a luxury, yes, but also a political statement. Dior was saying: we survived. Now we will thrive.

That is why this silhouette refuses to disappear. Every decade since Dior, from the ball gowns of the ’50s to the floral chiffons of the ’70s, from the minimalist reinterpretations of the ’90s to the crystal-crusted gowns of today, has found a way to redraw the X.

The X-line flatters because it collaborates with the body. If you have curves, it celebrates them; if you don’t, it creates them. It enhances balance: shoulder to hip, top to bottom. It works in cotton for day dresses, in taffeta for galas, in chiffon for bridesmaids.

It is also deliberate. Unlike an A-line, which can fall casually, the X-line demands tailoring, corsetry, or at least careful shaping. That effort translates into presence. You do not slouch in an X-line dress — the dress itself will not allow it.

The X-line is not only fashion but metaphor. The X is a cross, a meeting, a choice. The waist is the center, the place where control is held. To wear an X-line is to stand at that crossing, to place yourself at the very axis of proportion.

This is why, whenever fashion swings too far into formlessness — into oversized sweats, androgynous minimalism, deconstruction — the X-line eventually returns. Because we crave harmony. We crave the drama of a perfect waist. We crave the ritual of dressing up.

The X-line is couture’s most enduring love story. It began in the ashes of war, it reappeared in the glitter of the ’80s, it is walking the runways of 2025 in gowns that feel both historic and futuristic.

Fashion might reinvent fabrics, play with lengths, slash skirts, drop necklines, but the X always returns — because we cannot resist it. It is proportion made into poetry, beauty turned into architecture, survival turned into celebration.

The X-line is not simply worn; it is inhabited. It is the silhouette of confidence, of survival, of spectacle. It is history’s most flattering intersection — and it is never finished.