When skirts balloon, are they floating us toward liberation or trapping us in couture’s prettiest cage? The balloon teases — yet leaves us wondering what lies beneath the froth.

When skirts balloon, are they floating us toward liberation or trapping us in couture’s prettiest cage? The balloon teases — yet leaves us wondering what lies beneath the froth.

September 25, 2025

When skirts balloon, are they floating us toward liberation or trapping us in couture’s prettiest cage? The balloon teases — yet leaves us wondering what lies beneath the froth.

Fashion has always been at its most daring when it flirts with volume. Not the severe rigidity of corsets, nor the elongated austerity of columns, but volume that suggests levity, movement, the possibility of floating away from the earth. Enter the balloon silhouette, a shape that has repeatedly returned to the runway like an echo from a dream. Its charm lies in contradiction: an architecture of fabric that swells with drama, yet radiates girlish play. It is couture’s secret child — serious and mischievous, timeless and perishable, elegant and a little wicked.

When the balloon skirt appears, it carries the aura of laughter suspended in fabric. A bubble hem holds air like champagne holds fizz. It tells us that fashion is not simply about utility or body contour; it is also about suspension — of disbelief, of time, of gravity itself. This silhouette has remained eternal not because of constancy, but because of its cycle of disappearance and resurrection. Each return feels like a revelation: a skirt reborn, full of volume, full of daring, full of grace.

The balloon is a paradox stitched in satin and tulle. It narrows and cinches, but it also expands and lifts. It hides and reveals. It gives women the power to occupy more space while disguising their shape. It transforms the body into a floating sculpture, both untouchable and playful. Perhaps that is why it has remained so deeply lodged in the collective memory of style: because it speaks the language of transformation, and fashion, at its highest form, is transformation itself.

The balloon silhouette did not emerge in a vacuum. Like all silhouettes, it is an evolution — a whisper from the past reinterpreted for a new era. Its earliest ancestors can be traced back to the exaggerated structures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when crinolines and panniers gave European court dress its extravagant width. Those skirts, supported by cages and layers of petticoats, created domes of fabric around the body, symbols of status and wealth as much as style. They were impractical, yes, but they were also performative — declarations of social power in textile form.

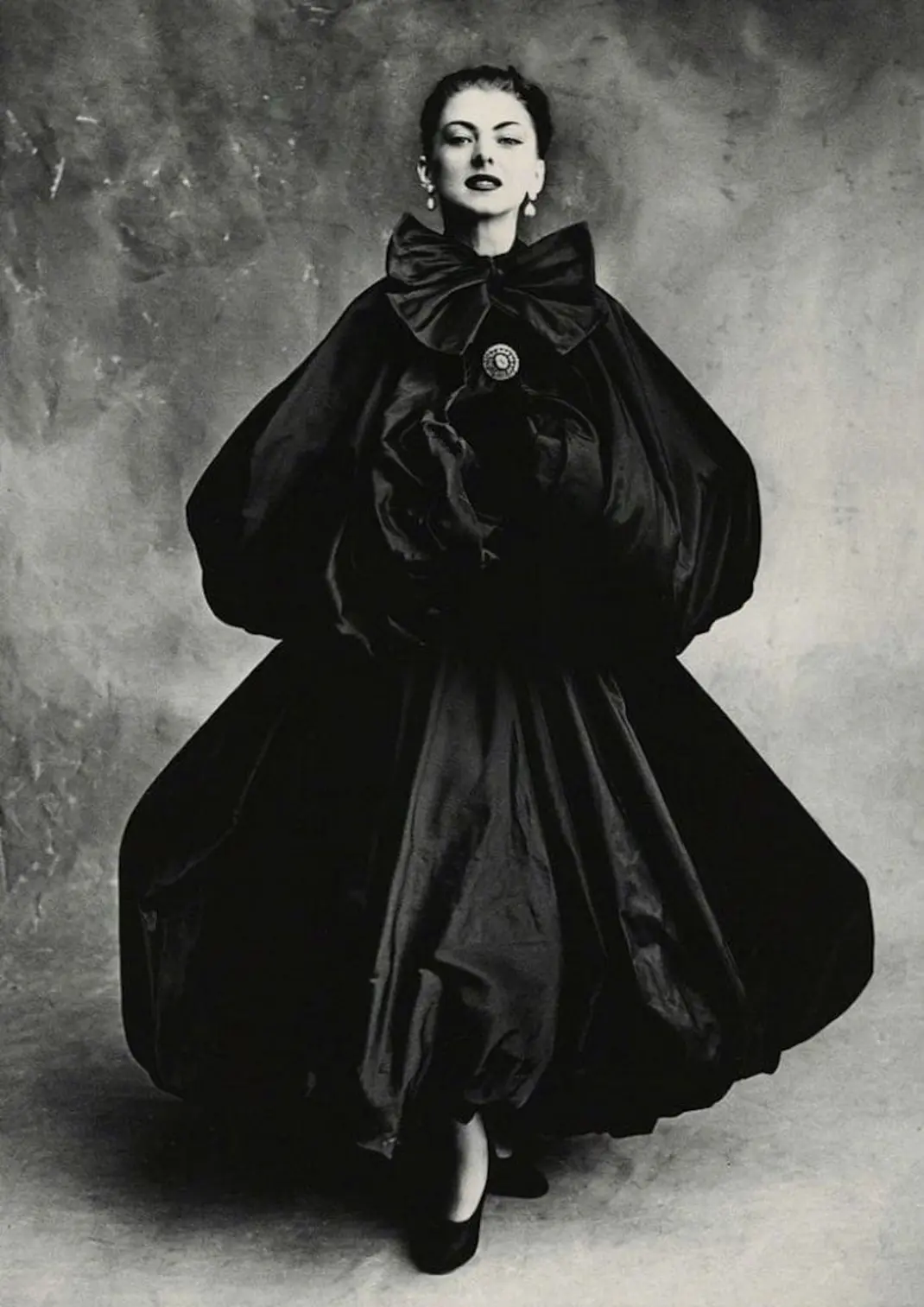

By the early twentieth century, such theatricality had vanished in favor of sleeker, body-conscious tailoring. Yet the ghost of volume never fully disappeared. The 1950s were a paradoxical decade: on one hand, conservative ideals of domestic femininity were reinforced; on the other, youth culture and postwar optimism generated playfulness in fashion. The balloon skirt was perfectly poised between the two. It could be formal — a satin cocktail dress fit for an embassy dinner — yet it could also be coquettish, a skirt that bounced as a girl danced to rock ’n’ roll. In 1954, Cristóbal Balenciaga — the master sculptor of couture — unveiled his cocktail balloon dress. Where others clung to the hourglass ideal, Balenciaga softened it, creating a silhouette that expanded outward rather than inward. The balloon was born not as mimicry of history, but as innovation: fabric inflated around the body, narrowing at hem or waist, transforming a dress into a buoyant form.

Three years later, Christian Dior crystallized the idea into fashion history. His 1954 red satin bubble dress remains one of the crown jewels of couture. It was mischievous in its defiance of the pencil-slim line then reigning, yet regal in execution. The skirt ballooned outward only to collapse inward at the hem, creating an optical trick: volume without mass, drama without weight. It was a garment that asked its wearer not merely to walk but to float.

This was a decade recovering from war, a generation ready for optimism, frivolity, a return to femininity. The balloon was joy sewn into fabric, an assertion that fashion could once again laugh. As the 1950s unfolded, designers across Paris embraced the look. Pierre Cardin exaggerated bubbles into futurist volumes; Yves Saint Laurent, in his early days at Dior, tested the silhouette as both dress and skirt. By 1959, the balloon was so entrenched in cultural imagination that The New York Times praised it as “one of the prettiest dance fashions for evening.”

Why was it “pretty”? Because the balloon was never static. It moved with the body, swayed with music, held within its folds the possibility of flirtation. Unlike the long skirts of the 1930s or the rigid wartime suits, this was a garment designed to be seen in motion — on dance floors, in nightclubs, in the swirl of society. It symbolized not restraint but release.

Yet, like all fashion phenomena, its moment faded. The 1960s brought mod minimalism and the rise of the mini. The 1970s chased fluidity in peasant skirts and disco glamour. The balloon silhouette seemed like a relic — until the 1980s came calling.

This was the decade of excess: power shoulders, gilded fabrics, electric colors, and silhouettes that refused to be subtle. In this climate, the balloon skirt was not merely revived — it was inflated, dramatized, and pushed into cultural mythology.

At the Cannes Film Festival in 1987, Diana stepped into legend wearing a navy and white bubble hem ensemble. The skirt swelled outward in soft folds before tapering at the knee, paired with a sharp jacket that contrasted volume with precision. In that moment, the bubble silhouette became more than a trend. It was royal rebellion disguised as play — a princess presenting herself not as porcelain but as flesh, air, and motion.

Diana’s balloon looks were numerous: cocktail dresses, evening gowns, playful daywear. Each garment balanced girlish frivolity with regal gravitas, as though the hemline itself carried her dual identity. For the public, the bubble skirt became synonymous with her charm. For fashion, it proved that a silhouette born in couture salons could thrive under the flashbulbs of global celebrity.

The 1980s also belonged to designers who thrived on theatricality. Christian Lacroix and Yves Saint Laurent, the French couturiers whose works embodied baroque excess, embraced the bubble with relish. For them, it was an ideal structure on which to layer embellishments: brocades, bows, gold trims. His balloon skirts were not merely voluminous; they were kaleidoscopes of fabric, excess incarnate.

Vivienne Westwood, too, toyed with bubble-like structures, though filtered through her punk romanticism. For her, exaggerated hems carried subversive undertones, mocking traditional femininity by inflating it to cartoonish scale. Where Lacroix gilded, Westwood rebelled. Yet both recognized the silhouette’s power: it was dramatic, photogenic, unapologetically theatrical. The bubble skirt’s return in the 1980s was not coincidental. This was a decade that celebrated “more”: more fabric, more color, more attitude.

The balloon silhouette has never been still; it drifts, transforms, reinvents itself with every gust of fashion’s changing wind. In the 2000s, it floated like painted clouds across Galliano’s Dior, theatrical and drenched in history, while Balenciaga under Ghesquière treated it like an architectural puzzle, inflating fabric into futuristic cocoons. Yves Saint Laurent’s balloon dresses swelled with baroque mischief, their decadent curves flaunting a naughty opulence that teased as much as they enthroned.

Zac Posen sent it to Hollywood, where frothy hems shimmered on red carpets like spun sugar, and Louis Vuitton wrapped it in Marc Jacobs’s playful decadence, teetering between girlish charm and indulgence.

By the 2010s, the puff had grown bolder, sharper. Balmain armed it with sequins and militant shoulders, a balloon no longer soft but commanding.

Ulyana Sergeenko bent it into folklore fantasy, airy skirts like storybook illustrations in motion. Alexandre Vauthier cut it short, sculpting bubbles of fabric that clung to the body while daring legs to steal the gaze — part puff, part provocation.

The 2020s brought the silhouette to extremes, its lightness turned into commentary. Moschino made a joke of its own name, balloon hems styled as literal balloons, inflating camp into couture.

Ashi Studio sculpted clouds so ethereal they seemed to hover rather than hang, proof that air could be carved like marble.

Marc Jacobs magnified volume to the edge of absurdity, drowning models in oceans of puff, daring us to ask if air could crush as well as lift.

George Keburia gave it irony, his balloon forms part shield, part satire, a wink at fashion’s obsession with excess. Christian Siriano’s balloon dresses swell with sculpted satin and architectural folds, turning volume into a bold celebration of glamour and unapologetic presence.

Floating, melting, expanding — the balloon silhouette has always been more than decoration. It is a vessel for contradiction: airy yet heavy with meaning, light as clouds yet brimming with strength, delicate and brazen at once. Each era redefines its puff, but none can make it vanish, because fashion always returns to air — to the dream of floating, and to the spectacle of watching that dream nearly burst.

The balloon silhouette never truly sinks; it floats, drifts, and returns, carried by the wind of fashion’s restless cycle. Like a boomerang, it always comes back, puffed with fresh air and new meaning. Its survival is not just about whimsy or excess — it endures because it symbolizes the eternal tension between body and fabric, power and play. The puff becomes a metaphor for fashion’s ability to expand beyond function, to exaggerate desire, to inflate status and spectacle. It embodies rebellion against restraint, yet also reveals how easily volume can disguise control. Each revival is a reminder that air, though invisible, holds weight in style: a floating promise of freedom, a teasing illusion of liberation, a spectacle that refuses to deflate because fashion itself is addicted to breathing new life into old forms.