From Christian Dior’s 1955 revolution to today’s runways, the A-line silhouette has endured as one of fashion’s most flattering and democratic forms — proof that true elegance lies in balance, not excess.

From Christian Dior’s 1955 revolution to today’s runways, the A-line silhouette has endured as one of fashion’s most flattering and democratic forms — proof that true elegance lies in balance, not excess.

September 27, 2025

From Christian Dior’s 1955 revolution to today’s runways, the A-line silhouette has endured as one of fashion’s most flattering and democratic forms — proof that true elegance lies in balance, not excess.

Fashion in the 1950s was still shadowed by the wartime decade: rationing, rigid corsetry, and silhouettes that owed more to utility than romance. Then came Christian Dior, the man who had already reset the industry in 1947 with his famed New Look, cinching waists and flaring skirts in a triumphant return to femininity.

But by 1955, Dior sensed the mood had shifted again. Women wanted freedom as well as beauty. And so came his A Line collection: clothes that traced the form from shoulder to hip before swinging outward in a gentle flare, sketching the unmistakable shape of a capital “A.”

It was a masterstroke. Gone were the exaggerated hourglass forms; instead, Dior offered balance and ease. His A Line coats and dresses were sophisticated yet practical, a silhouette that released women from rigid foundations without stripping away grace. In that single season, he created not only a collection but also a concept — a term that would become part of fashion’s permanent vocabulary.

What followed was a rare thing in fashion: a design that leapt instantly from couture salons to the wider world. Dior’s “A” was soon echoed in the trapeze dresses of Yves Saint Laurent, then his young protégé, who carried the spirit of freedom into the 1960s. By the middle of that decade, the A-line had become universal, reinterpreted by everyone from André Courrèges with his futuristic minimalism to American department stores selling accessible versions for the everyday women.

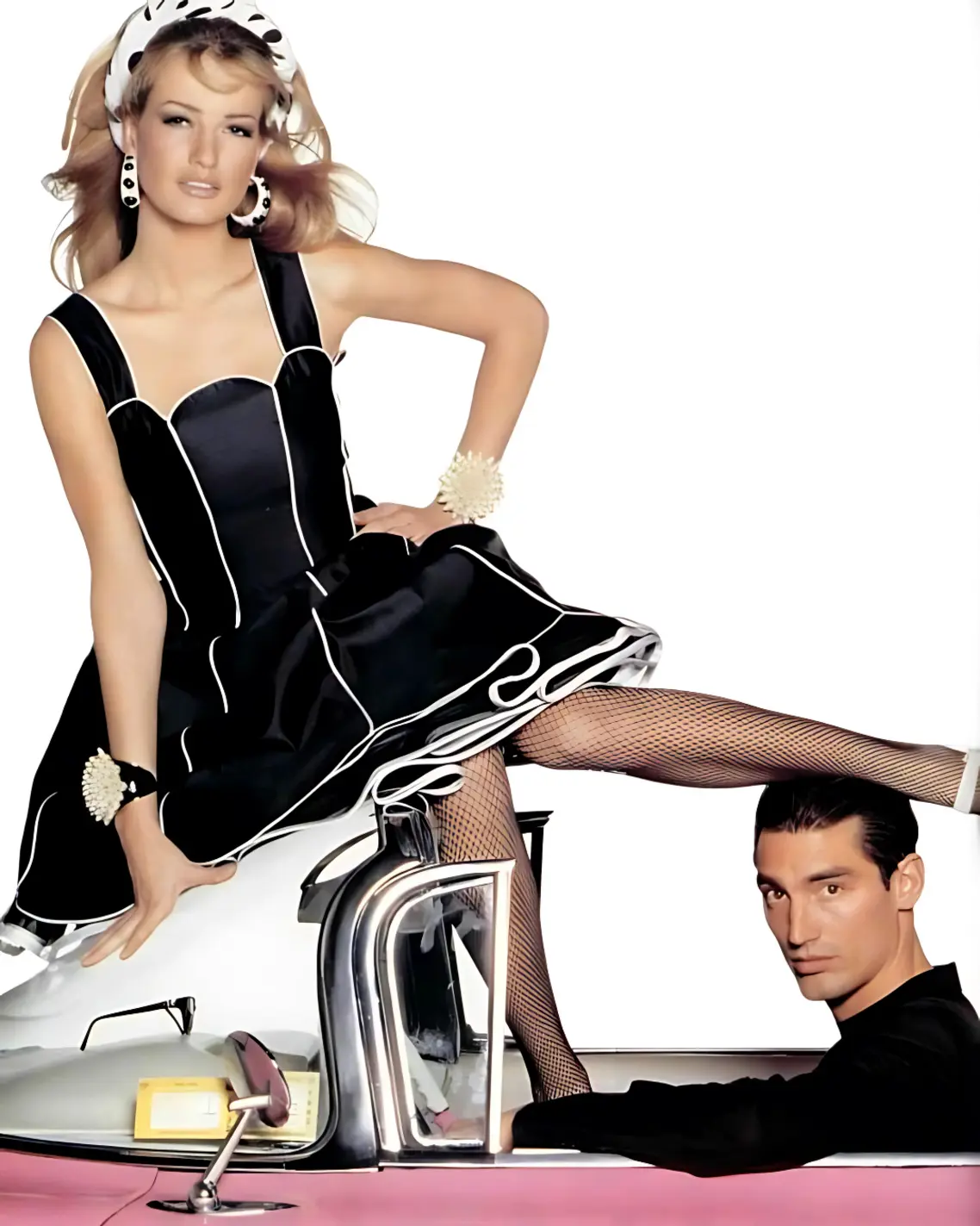

The genius of the A-line was not simply in its shape but in its adaptability. Whether cut in wool crepe for the office, duchess satin for a cocktail party, or cotton for a weekend stroll, the line delivered both elegance and versatility. It democratized couture ideas, offering women a wardrobe that moved with the times.

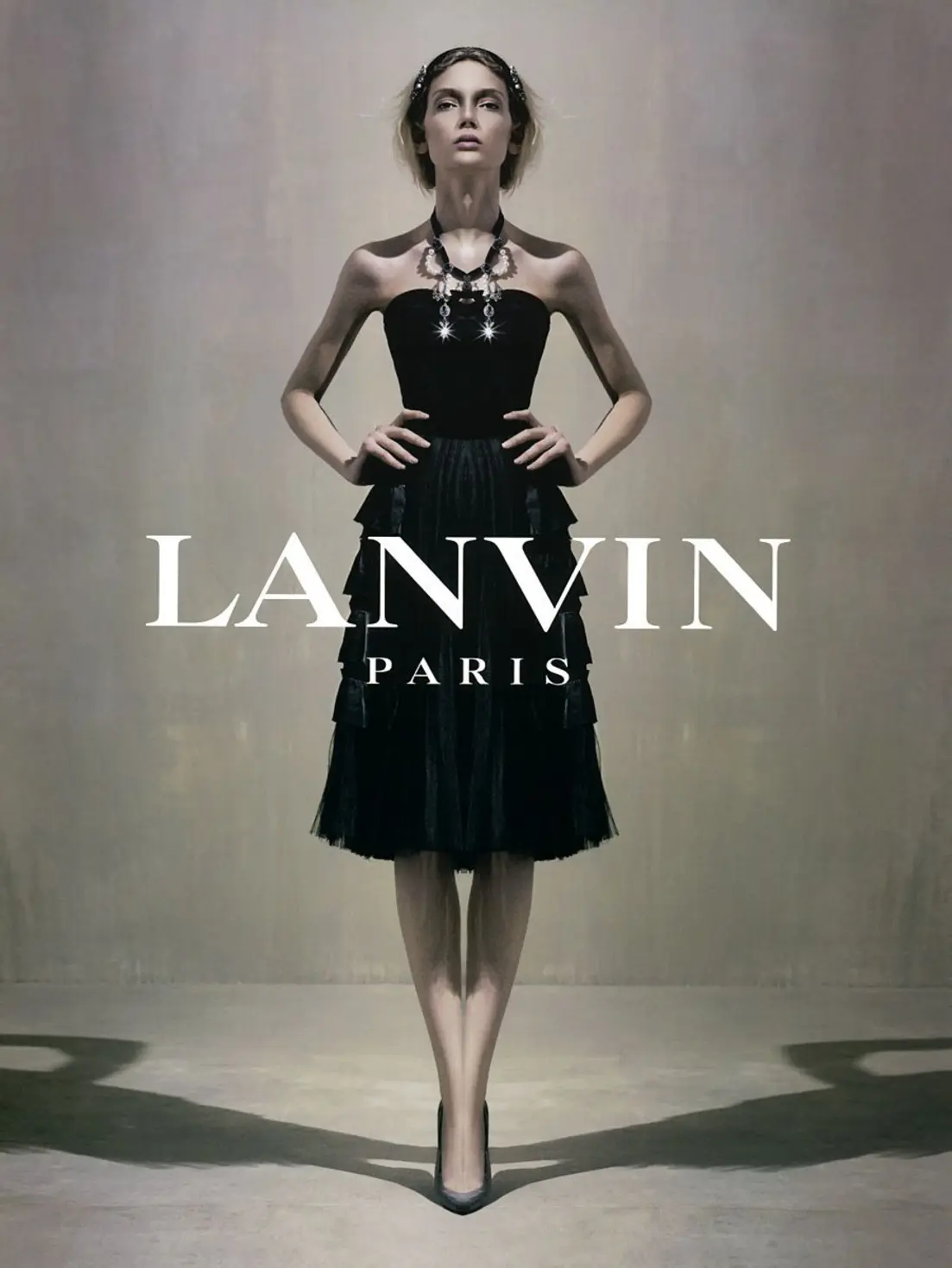

Designers across the decades have returned to the A-line with reverence, each giving it a fresh inflection.

At Oscar de la Renta, the silhouette became the foundation of fairytale gowns — revived most recently under Laura Kim and Fernando Garcia, who treat it as a canvas for vibrant florals and embroidered detail.

Their Spring 2025 show, staged amid the cherry blossoms of the New York Botanical Garden, elevated the line into poetry: dresses that glowed like stained glass, inspired by Garcia’s own watercolor orchids.

For Zac Posen, the A-line offered a chance to blend structure and softness. His Spring 2014 collection, inspired by Impressionist painting, sent organza and silk satin gowns floating down the runway like brushstrokes. The A-line there was not an absence of shape but a study in balance — architectural precision softened by a haze of romance.

Even Rodarte, with its reputation for experimental craft, found in the A-line a useful vessel. A 2012 campaign featuring Coco Rocha showed the silhouette in its modern guise: layered, almost sculptural, yet retaining that essential swing that makes the line so wearable.

The A-line may appear effortless, but its perfection is a matter of discipline. The flare must start at just the right point — too high and the dress looks juvenile, too low and it becomes ungainly. The darts and seams must be precisely angled so that the garment skims rather than clings. Pattern-cutting of this kind is invisible artistry: the better it is done, the less it is noticed.

This is why a truly successful A-line is not simply a straight cut but an architectural exercise. The slope of the fabric, the drape at the hem, the angle of movement — all must align to create that seemingly simple triangle. In this sense, the silhouette has always been a couturier’s challenge, requiring a marriage of technical skill and intuitive elegance.

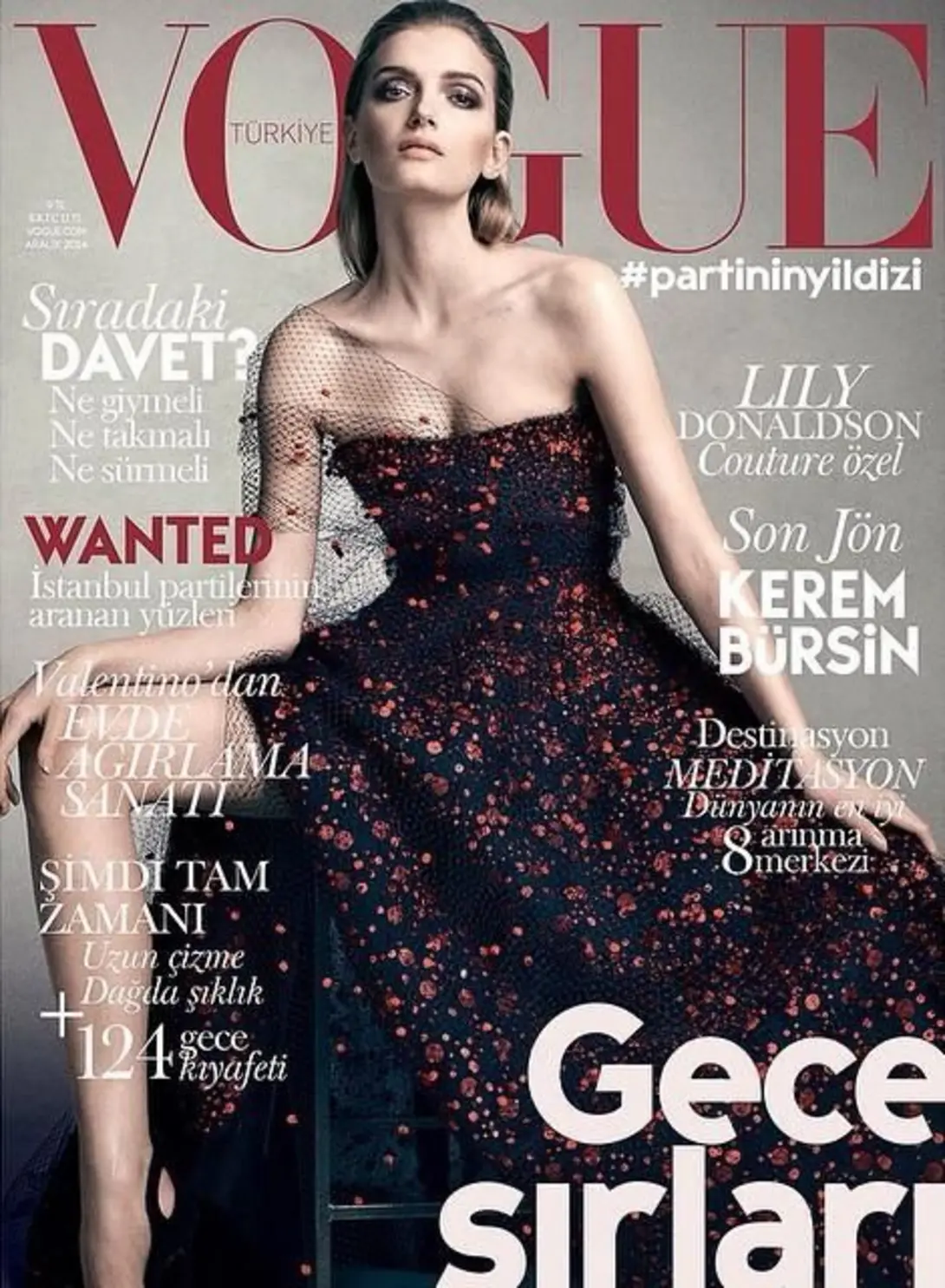

In a fashion world that constantly demands reinvention, the A-line has survived for seventy years with minimal alteration. Its power lies in its neutrality. The silhouette flatters without dictating, offering a frame in which the wearer’s individuality can shine. Unlike bodycon dresses that insist on exposure, or oversized shapes that swamp the figure, the A-line is democratic: it works for all heights, builds, and ages.

That very neutrality also makes it a commercial triumph. From couture houses to high-street retailers, the A-line continues to sell, season after season, because it feels both modern and classic. In moments of excess, it reads as restraint; in moments of minimalism, it carries romance. It is, in short, a shape that never jars.

Beyond the technical and commercial lies something deeper: the A-line as a cultural symbol. To wear one is to project quiet confidence. It does not demand attention like a plunging neckline or a body-sculpted sheath. Instead, it suggests assurance — the kind of elegance that knows it does not need to shout.

Perhaps that is why the A-line has proved so enduring. It carries within it Dior’s original promise: that fashion can liberate as well as adorn. In every decade since 1955, women have found in the A-line a garment that allows them to move, work, and live, while still inhabiting a silhouette of grace.

In an era where fashion often oscillates between the extremes of spectacle and streetwear, the A-line stands as a reminder that the most radical statement can sometimes be the simplest. A shape traced in air seventy years ago continues to whisper through wardrobes today — not as nostalgia, but as proof that true elegance is timeless.