The peg-top silhouette explodes at the hips, strangles at the ankles, and turns every corridor into a catwalk of suspense. It purrs with exotic fantasies, crackles with modernist geometry, and teases authority while giggling at fragility. Was it a bold promise of freedom, a sly trap of elegance, or simply fashion’s wicked joke on women’s desire to dazzle? A century later, its cheeky contradictions still intoxicate designers chasing danger in beauty.

The peg-top silhouette explodes at the hips, strangles at the ankles, and turns every corridor into a catwalk of suspense. It purrs with exotic fantasies, crackles with modernist geometry, and teases authority while giggling at fragility. Was it a bold promise of freedom, a sly trap of elegance, or simply fashion’s wicked joke on women’s desire to dazzle? A century later, its cheeky contradictions still intoxicate designers chasing danger in beauty.

September 28, 2025

The peg-top silhouette explodes at the hips, strangles at the ankles, and turns every corridor into a catwalk of suspense. It purrs with exotic fantasies, crackles with modernist geometry, and teases authority while giggling at fragility. Was it a bold promise of freedom, a sly trap of elegance, or simply fashion’s wicked joke on women’s desire to dazzle? A century later, its cheeky contradictions still intoxicate designers chasing danger in beauty.

Fashion history is never linear. It is marked by abrupt shifts, rebellions against form, and the eternal push-and-pull between structure and freedom. The peg-top silhouette belongs to one of those seismic shifts. Emerging between 1908 and 1914, it disrupted the long-standing S-bend corseted ideal that had shaped women’s bodies through restriction and exaggeration.

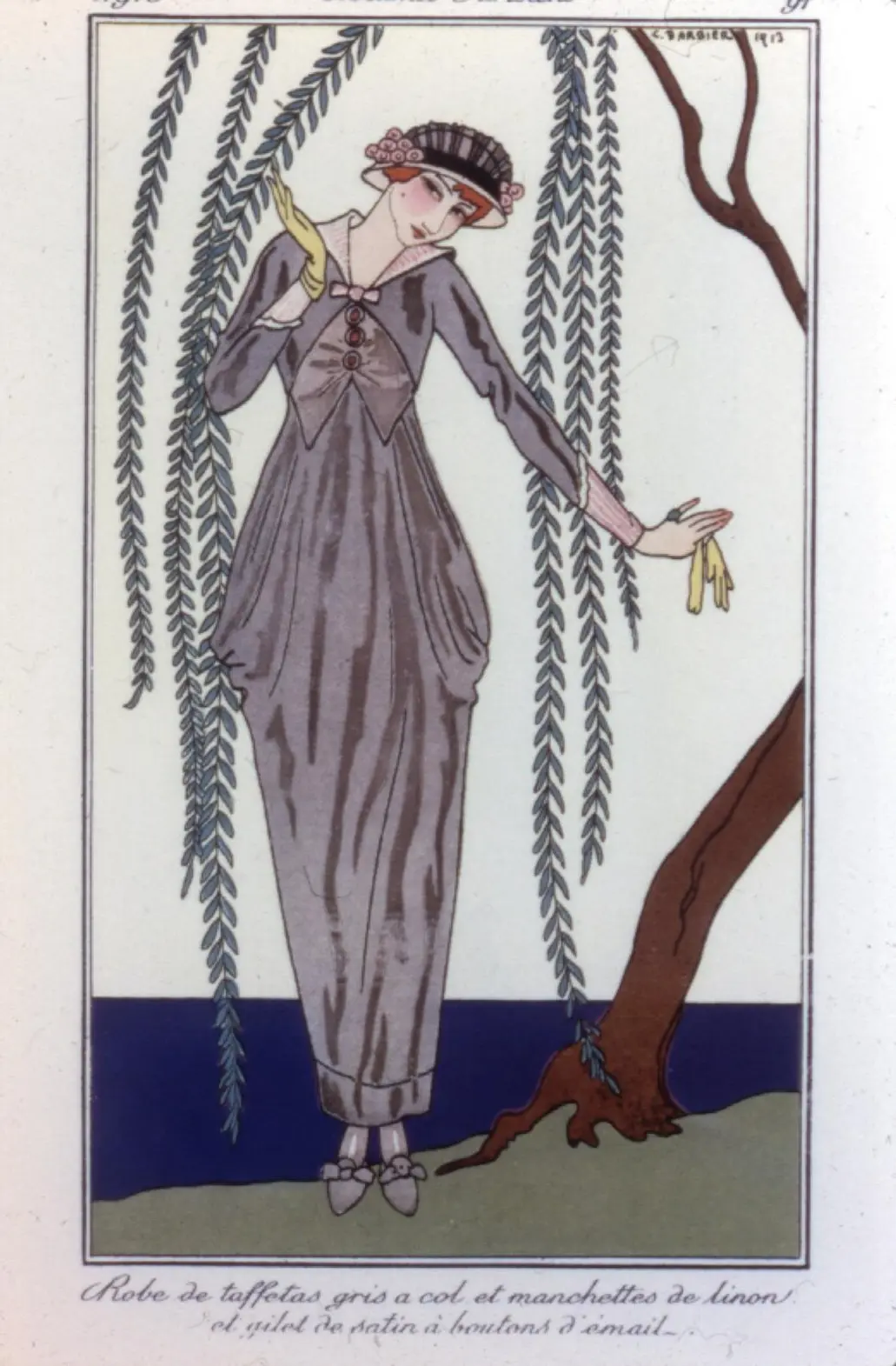

The peg-top silhouette marked a radical departure. Its premise was simple yet visually commanding: volume at the hips, narrowing to the ankles. This “pegging” created a ballooning effect that accentuated curves but forced the fabric back inward, binding the stride. It was at once natural and unnatural. Natural because it allowed the body’s waist and hip curves to emerge without the iron frame of corsets; unnatural because the tapering hem constrained a woman’s movement, echoing the infamous hobble skirt.

Designers in Paris, particularly those working along the Rue de la Paix, pioneered this look.

Thus, the peg-top silhouette was not merely a fleeting curiosity. It was a dialogue between past and present, East and West, form and function, discipline and play.

The peg-top silhouette was not subtle. It startled, provoked, and sometimes amused. Critics likened the skirts to saddlebags or pocket balloons, creating exaggerated hips that clashed with the streamlined torso above. The effect was theatrical: a woman appeared anchored, her body’s weight concentrated around the hips, yet visually elongated by the tapering descent to the ankles.

The impression was twofold. On one hand, it amplified sensuality, tracing the waist and swelling over the hips like sculptural drapery. On the other, it mocked movement, forcing women to adopt shorter, smaller steps. A tailor in 1912 famously remarked that in an emergency, a woman in peg-top skirts would have to “hop like a kangaroo.” The silhouette, therefore projected elegance at the expense of practicality, turning walking itself into performance.

Yet therein lay its allure. The restriction was not a regression but a paradoxical expression of control. Women who wore peg-top clothing declared their ability to navigate difficulty with poise. The asymmetry of seams, the gleam of metallic fabrics, the intentional awkwardness of narrowed hems—all contributed to an impression of sophistication with an edge of daring.

The aesthetic also resonated with the cultural fascination for the Orient. The hobble skirt, a close cousin of the peg-top, drew from Western imaginings of Eastern women taking delicate, mincing steps. In Paris and London, this image translated into garments that blended sensual exoticism with modern construction. The peg-top thus became a garment of spectacle: to wear it was to be both admired and challenged, a figure caught between admiration and critique.

What, then, did the peg-top silhouette symbolize? At its essence, it embodied contradiction, for every gesture of liberation it offered was immediately counterbalanced by a gesture of restraint. By moving away from the S-bend corset, it allowed the female body to emerge with greater naturalness, no longer forced into the exaggerated curvature of the previous decade. Yet this new freedom at the waist and hips was offset by the constricting narrowness at the hem, which restricted movement and reduced walking to delicate, measured steps. This paradox of release and confinement reflected the condition of women in the early twentieth century, who were advancing in education, politics, and professional life, but remained bound by deeply ingrained social expectations that limited their autonomy.

The gown’s very construction reinforced this duality, for it spoke simultaneously of modernity and exoticism. The geometric brocade of Cauët’s 1913 design, with its angular florals and asymmetrical seams, resonated with the visual language of modernist art, anticipating Cubism and Art Deco before these movements reached their peak. At the same time, the silhouette’s narrowing at the ankles recalled the West’s imagined vision of the East, where femininity was associated with delicacy and constrained steps. Thus, the peg-top became a garment caught between worlds: it was progressive yet nostalgic, Western yet infused with an exotic fantasy, a shape that dramatized the cultural tensions of its time.

To wear the peg-top silhouette was therefore to inhabit a space of both power and fragility. The ballooning hips projected authority, commanding the eye and amplifying a woman’s presence in public. Yet the very restriction of the hem made that power precarious, since elegance could dissolve into vulnerability with a stumble, a torn seam, or a clumsy step. In this balance of spectacle and risk, the silhouette captured the unstable ground on which women stood—visible and commanding, yet still subject to structures that could undo their authority at any moment. The peg-top’s symbolic power lay precisely in this tension, making it less a fleeting trend than a cultural mirror of an age negotiating between progress and tradition, freedom and control.

In the early 2000s, Dolce & Gabbana adored the peg-top’s natural drama. Their skirts swelled at the hips like ripe Sicilian fruit before slimming to a narrow hem, transforming runways into catwalks of sensual provocation. It felt like women carried entire Baroque altarpieces on their hips—ornate, voluptuous, untamed. Lanvin under Alber Elbaz carried it into quiet elegance, polishing the hips with ruching and draping so the volume felt sensual rather than flamboyant.

At the same moment, Alexander McQueen wielded the peg-top like a weapon. In his collections, hips erupted with fabric, then sliced back into lean, knife-sharp tapering. The silhouette became dark theater: a woman who walked in McQueen’s peg-top skirt looked like she was defying gravity while seducing danger.

Dior under John Galliano played the silhouette with coquettish refinement, blending bias cuts with pegged skirts in lush satins. Between them, the peg-top became a paradoxical whisper: at once exuberant and restrained, glamorous yet mysterious.

As the 2010s dawned, Ulyana Sergeenko spun the peg-top into fantasy. Her skirts evoked Russian fairy tales—hips blooming like onion domes, hems cinched like storybook secrets. Each look promised romance and danger, a modern tsarina striding with the confidence of folklore heroines.

Thom Browne, meanwhile, treated the peg-top like a joke with teeth. In his surrealist suiting, skirts ballooned at the hips before clamping shut around the calves. Office wear became absurd theater—secretaries turned into queens, businessmen into clowns. The peg-top found irony here, a playful rebellion against uniformity.

By the 2020s, the peg-top became bolder, louder, hungrier. Harris Reed resurrected it as a genderless fantasy—hips dressed in miles of satin, shapes so wide they bordered on wings. His peg-top gowns did not whisper, they thundered: walking altars of self-expression.

Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing approached the silhouette with power dressing in mind. He armored hips in metallic leathers, rigid curves that looked like sculpture.

Peg-top skirts became weapons of authority, turning the runway into a battlefield of seduction.

George Keburia injected the silhouette with Georgian futurism. His peg-top skirts looked like costumes for space heroines, mixing rigid geometry with playful irony.

Maison Margiela, under John Galliano, re-imagined the form through deconstruction. Pegged shapes were torn, rebuilt, wrapped in transparent fabrics, re-stitched like fashion ghosts.

Ashi Studio crowned the decade with pure spectacle: peg-top gowns swelling into architectural cathedrals, gowns that turned hips into monuments of romance.

Fashion recycles not merely because of nostalgia, but because certain forms contain eternal dialogue. The peg-top silhouette belongs to this category. Designers return to it because its contradictions remain unresolved, its lines endlessly provocative.

What ensures its endurance is versatility. The silhouette can be severe or playful, subtle or outrageous. It can be cut in silk brocade for the ballroom or in denim for streetwear. It speaks equally to gender-neutral tailoring and feminine ornament. And above all, it dramatizes movement itself: the way fabric swells, folds, and contracts around the body.

The peg-top silhouette also remains a metaphor for modern life. It reflects how freedom often arrives paired with constraint, how beauty emerges from struggle, and how contradictions define identity. For women in 1913, it meant balancing elegance with restricted steps. For designers today, it symbolizes the tension between heritage and innovation.

The peg-top silhouette, then, is not merely a fashion footnote. It is a reminder of how clothing records history—social change, gender politics, cultural imagination—all woven into seams and hems.

The peg-top silhouette is a paradox made fabric. It liberated women from corseted distortion while binding their stride. It borrowed from exotic fantasy while pointing to modernist abstraction. It symbolized both power and fragility. Its history, from Paris couture gowns to factory trousers, reveals how silhouettes can shape not only bodies but identities.

Today, designers continue to mine its tension: the ballooning hip, the tapering leg, the spectacle of restriction made beautiful. It is not nostalgia that keeps the peg-top silhouette alive, but its capacity to provoke, to inspire, to remind us that fashion thrives on contradiction.

In every reappearance, the peg-top silhouette proves itself not just a relic but a language—one that whispers of elegance, shouts of restriction, and sings of the eternal dialogue between freedom and form.