In contrast to the excessiveness of mass concrete blocks and towering glass walls, Frei Otto emerged as a poet of space.

In contrast to the excessiveness of mass concrete blocks and towering glass walls, Frei Otto emerged as a poet of space.

September 20, 2025

In contrast to the excessiveness of mass concrete blocks and towering glass walls, Frei Otto emerged as a poet of space.

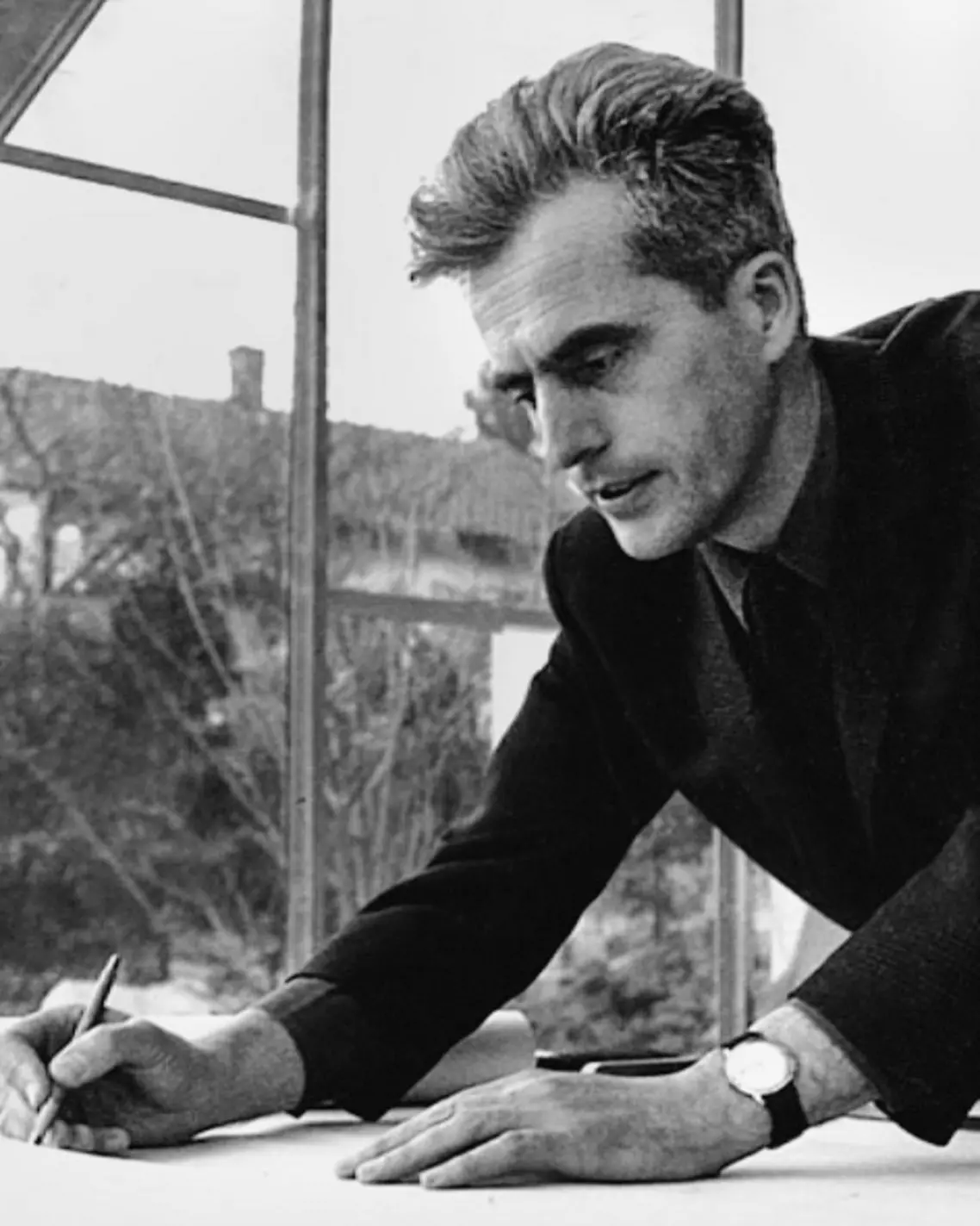

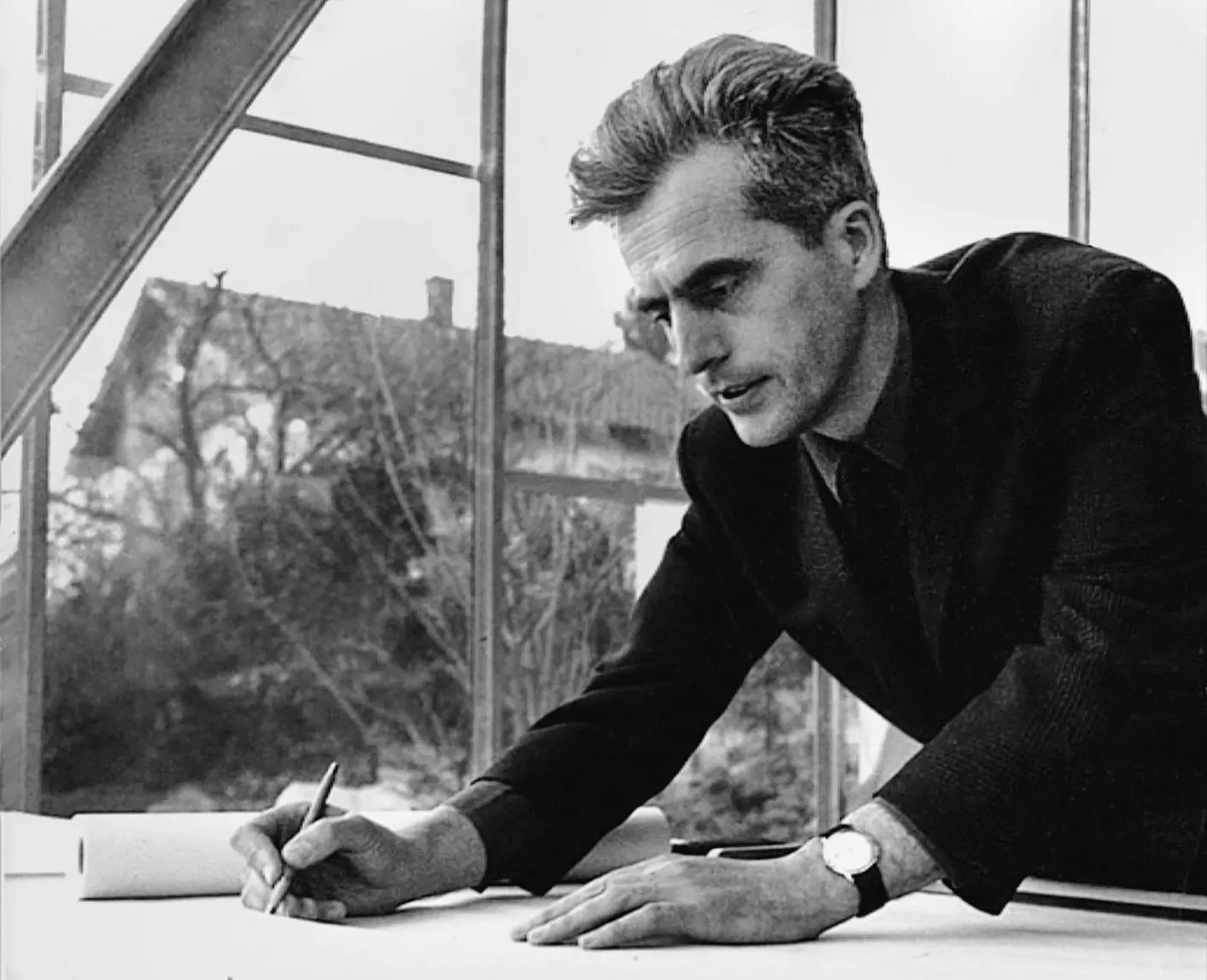

Frei Otto architectural legacy stands in sharp contrast to the excessiveness of mass concrete blocks and towering glass walls that defined much of 20th-century architecture. Emerging as a poet of space, Frei Otto envisioned buildings not as monuments of permanence, but as living systems—structures that breathe, adapt, and move in harmony with nature.

Frei Otto architectural legacy was forged not in studios of luxury, but in the aftermath of war and displacement. His early experiences during World War II shaped a philosophy rooted in reconstruction, restraint, and the urgent need to build lightly on a wounded world.

Frei Otto came of age during one of the most turbulent periods in human history. Initially studying architecture, he was soon swept into the currents of World War II, serving as a Luftwaffe pilot in its final years. However, it was not destruction that would define his legacy — it was creation. After the war, as a prisoner of war in a camp near Chartres, France, Otto began to explore the very first ideas that would later blossom into an architectural revolution.

Shaped by the devastation of World War II and the urgent need for reconstruction, Otto—deeply critical of the monumental heaviness of Third Reich architecture—found, in the stillness of confinement, the quiet space to sketch, reflect, and begin his lifelong pursuit of lightness, mobility, and ecological harmony.

Upon release, Otto resumed his studies and eventually traveled to the United States, where he encountered the great minds of modern architecture — Erich Mendelsohn, Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, whose dictum “less is more” is deeply admired by Otto. These encounters refined his perspective, but Otto’s path would diverge in radical ways: where others built monuments of permanence, he envisioned structures that could dance with the wind.

Frei Otto’s career is a continuous exploration of the question: how can we build more with less? Long before sustainable architecture entered mainstream discourse, Frei Otto architectural legacy embodied its core values through lightweight architecture and tensile structures. He challenged the idea that grandeur required mass. Instead, he showed that a pavilion, a bridge, even a stadium could be built from a dance of tension and curvature, consuming fewer materials and leaving a lighter footprint.

His work on the Mannheim Multihalle in 1974 epitomized this principle. The hall’s undulating timber grid-shell was an engineering marvel, assembled from thin strips of wood into a flowing, cathedral-like form. It was both majestic and modest — a triumph of economy and elegance. Otto’s pedestrian bridge in Mechtenberg, spanning over 30 meters, further proved that even utilitarian infrastructure could be sculptural and sensitive to its surroundings.

His constructions were rarely solo endeavors. Otto frequently partnered with experts from physics, biology, and engineering, believing that complexity required collaboration. This interdisciplinary spirit became a model for the integrated, responsive architecture of today.

From the 1950s onward, his work at exhibitions such as the German Federal Garden Show stunned audiences with its elegance and innovation. His pavilions, often made of lightweight membranes and grid-shells, were functional and beautiful, they could also be dismantled easily, leaving no scar on the land. One of the most iconic examples was the German Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal. Pre-fabricated in Germany and assembled in record time, the pavilion demonstrated an efficiency and grace that few believed possible.

Then came his masterpiece: the roof of the Olympic Stadium in Munich for the 1972 Summer Games. A sweeping canopy of tensile cables and transparent panels, the structure redefined what large-scale public architecture could look and feel like. It wasn't just a roof—it was a statement, a metaphor, a cloud made solid.

Frei Otto strongly believed that natural forms held the solutions to our most pressing design challenges. This belief became a defining pillar of Frei Otto architectural legacy, influencing generations of architects exploring sustainable architecture and bio-inspired design.

This philosophy wasn’t just poetic—it was profoundly practical. In 1964, he founded the Institute for Lightweight Structures (IL) in Stuttgart, now the Institute for Lightweight Structures and Conceptual Design. The University of Stuttgart became a hub of interdisciplinary exploration, where scientists and designers collaborated to create sustainable, adaptive solutions. Otto’s works were not isolated sculptures but rather systems—frameworks that evolved from and responded to their environment.

In 2015, Frei Otto became the first posthumous recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, cementing his place in global architectural history. The Pritzker Prize jury recognized this singular devotion to ecological balance and innovation. The committee recognized Otto’s "visionary ideas, inquiring mind, belief in freely sharing knowledge and inventions, his collaborative spirit and concern for the careful use of resources".

In the Middle East, Frei Otto architectural legacy found one of its most poetic expressions. His lightweight, climate-responsive structures resonated deeply with desert landscapes shaped by sun, wind, and spirituality.

One such project was the Intercontinental Hotel & Conference Centre in Mecca, completed in 1974 in collaboration with architect Rolf Gutbrod. For the conference center, Otto designed a striking tent-like structure that evoked the nomadic heritage of the region while addressing the environmental demands of desert heat. This poetic blend of tradition and innovation earned Otto the 1980 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, a prestigious honor recognizing excellence in architecture for Muslim societies.

Another standout project is the Tuwaiq Palace in Riyadh, completed in 1985. In collaboration with Buro Happold and Omrania & Associates, Otto created a complex of flowing, tensile roofs that seem to rise organically from the desert floor. The palace balances light and shadow, enclosure and openness—creating an oasis for reflection, diplomacy, and ceremony. The project was awarded the 1998 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, further cementing Otto’s legacy in the region.

Otto’s influence extended even beyond these landmark works. He consulted on the famous folding umbrella canopies installed outside the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, providing shade for thousands of worshippers during prayer.

Otto pioneered a gentler way of shaping the world. His architecture coexisted with nature, embodying restraint, elegance, and profound respect for ecological balance. Decades later, Frei Otto architectural legacy remains foundational to sustainable architecture, offering a blueprint for building lightly in an era of climate urgency. Rooted in lightness, sensitivity, and freedom, his work feels more relevant than ever. Fittingly, “Frei” means “free” in German—and through his architecture, Frei Otto truly lived up to his name.