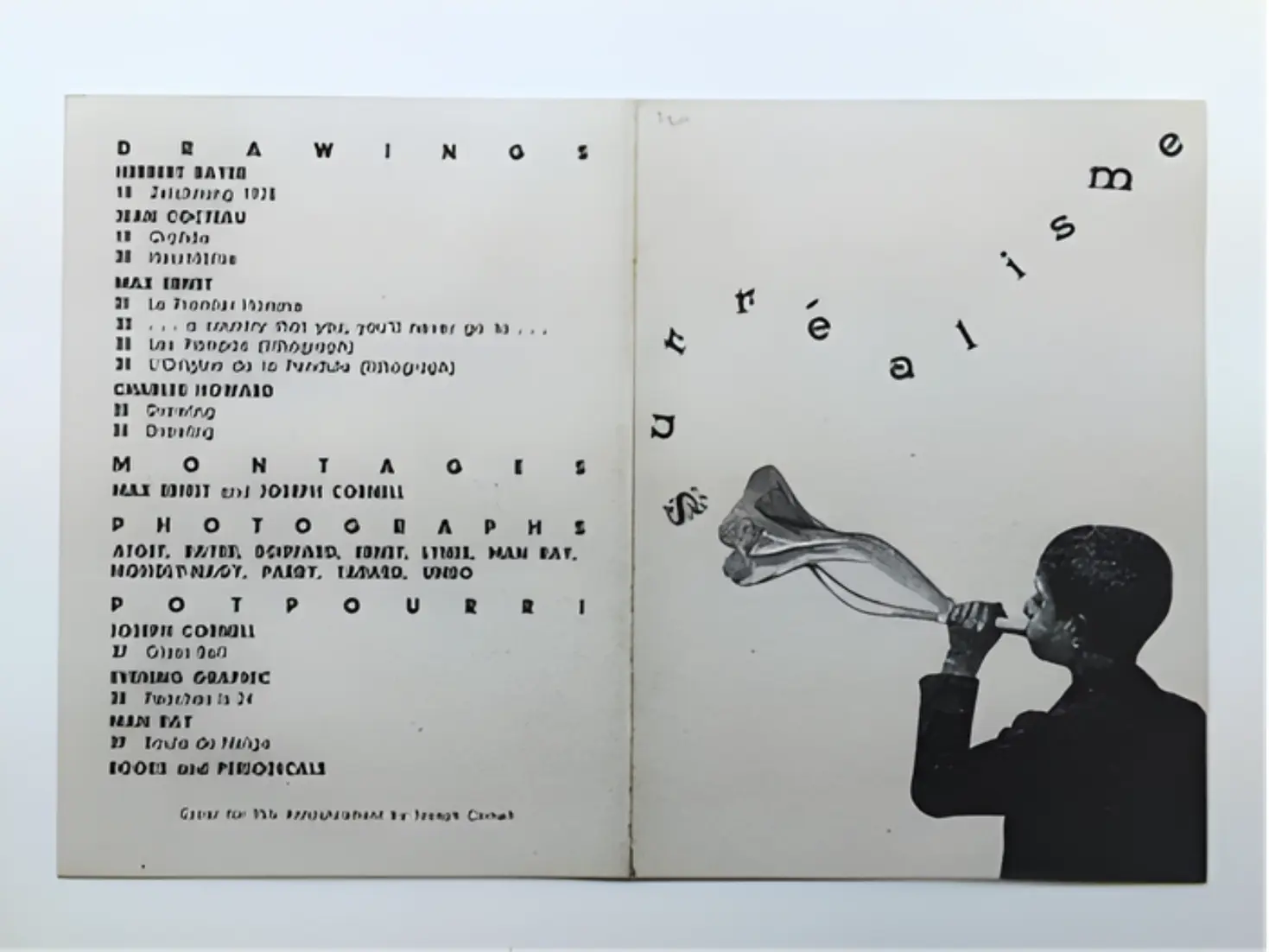

On January 29, 1932, the Julien Levy Gallery introduced Surrealism to New York, led by Salvador Dalí and The Persistence of Memory.

On January 29, 1932, the Julien Levy Gallery introduced Surrealism to New York, led by Salvador Dalí and The Persistence of Memory.

January 10, 2026

On January 29, 1932, the Julien Levy Gallery introduced Surrealism to New York, led by Salvador Dalí and The Persistence of Memory.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Julien Levy Gallery stood as one of only a handful of serious art galleries operating in Manhattan. It quickly became a major destination for Surrealist art, photography, and experimental film. Solo exhibitions passed through its doors featuring artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Frida Kahlo, Man Ray, Joseph Cornell, and, most prominently, Arshile Gorky. Many of the twentieth century’s most revered works of modern art circulated through the gallery, establishing it as a fundamental resource for artists who later defined Abstract Expressionism.

At the heart of the 1932 exhibition stood Salvador Dalí, whose work embodied Surrealism’s most unsettling contradictions. Dalí fused meticulous, almost Renaissance-level technique with imagery drawn from paranoia, desire, and psychological tension. His desolate landscapes populated by distorted forms and uncanny objects felt simultaneously hyperreal and hallucinatory. For many visitors, this exhibition marked their first encounter with art that privileged inner truth over rational order.

Painted in 1931, The Persistence of Memory emerged as the exhibition’s defining image. Its melting clocks draped across a barren landscape transformed time into something fluid and unstable, suggesting that memory and perception outweighed mechanical certainty. In Depression-era America, the image resonated deeply, reflecting a shared atmosphere of uncertainty and emotional dislocation.

Dalí’s work appeared alongside other major figures who expanded Surrealism’s intellectual reach. Marcel Duchamp challenged inherited definitions of art through conceptual provocation, while Jean Cocteau contributed a poetic, mythic sensibility that blurred boundaries between literature, drawing, and visual symbolism. Together, they framed Surrealism as a wide-ranging cultural project rather than a single visual style.

Crucially, the exhibition also elevated American talent. Cornell’s box constructions introduced a quieter, introspective Surrealism shaped by found objects, nostalgia, and private fantasy. His presence confirmed that Surrealist ideas could flourish on American soil and evolve into something distinctly personal.

The January 29, 1932 Surrealism exhibition achieved far more than the presentation of artworks. It staged a confrontation between rational modern life and the unruly subconscious. By uniting Dalí, Duchamp, Cocteau, and emerging American voices within the Julien Levy Gallery, the exhibition secured Surrealism as a vital force in the United States and helped redirect New York’s artistic future toward decades of experimentation shaped by dreams, memory, and imagination.