The hourglass silhouette is more than a shape. It is a cultural and sartorial statement deeply embedded in hourglass figure fashion and celebrity iconography. From Victorian corsets to red-carpet gowns, from Margot Robbie in The Wolf of Wall Street to Roberto Cavalli’s body-conscious collections, this enduring ideal fuses power, allure, and the exquisite art of shaping desire.

The hourglass silhouette is more than a shape. It is a cultural and sartorial statement deeply embedded in hourglass figure fashion and celebrity iconography. From Victorian corsets to red-carpet gowns, from Margot Robbie in The Wolf of Wall Street to Roberto Cavalli’s body-conscious collections, this enduring ideal fuses power, allure, and the exquisite art of shaping desire.

September 27, 2025

What happens when the female form becomes both architecture and provocation—when a silhouette transcends flattery to direct the gaze, and enchant without mercy?

The hourglass silhouette is not merely a shape—it’s a ritual. A choreography of curves, discipline, and instinct. The lifted bust demands attention, the cinched waist tightens every breath, the full hip declares desire without negotiation. The hourglass doesn't ask to be admired—it sets the standard, dazzling with intensity, refined with coolness, and charged with irresistible control.

Every step becomes punctuation. Satin clings like intention, seams slice through space like whispered commands. The woman inside this silhouette does not seek approval—she owns the room. Part divine seductress, part modern minimalist, she blends fire and restraint into a presence that turns fashion into submission. Eyes follow her not by invitation, but by instinct.

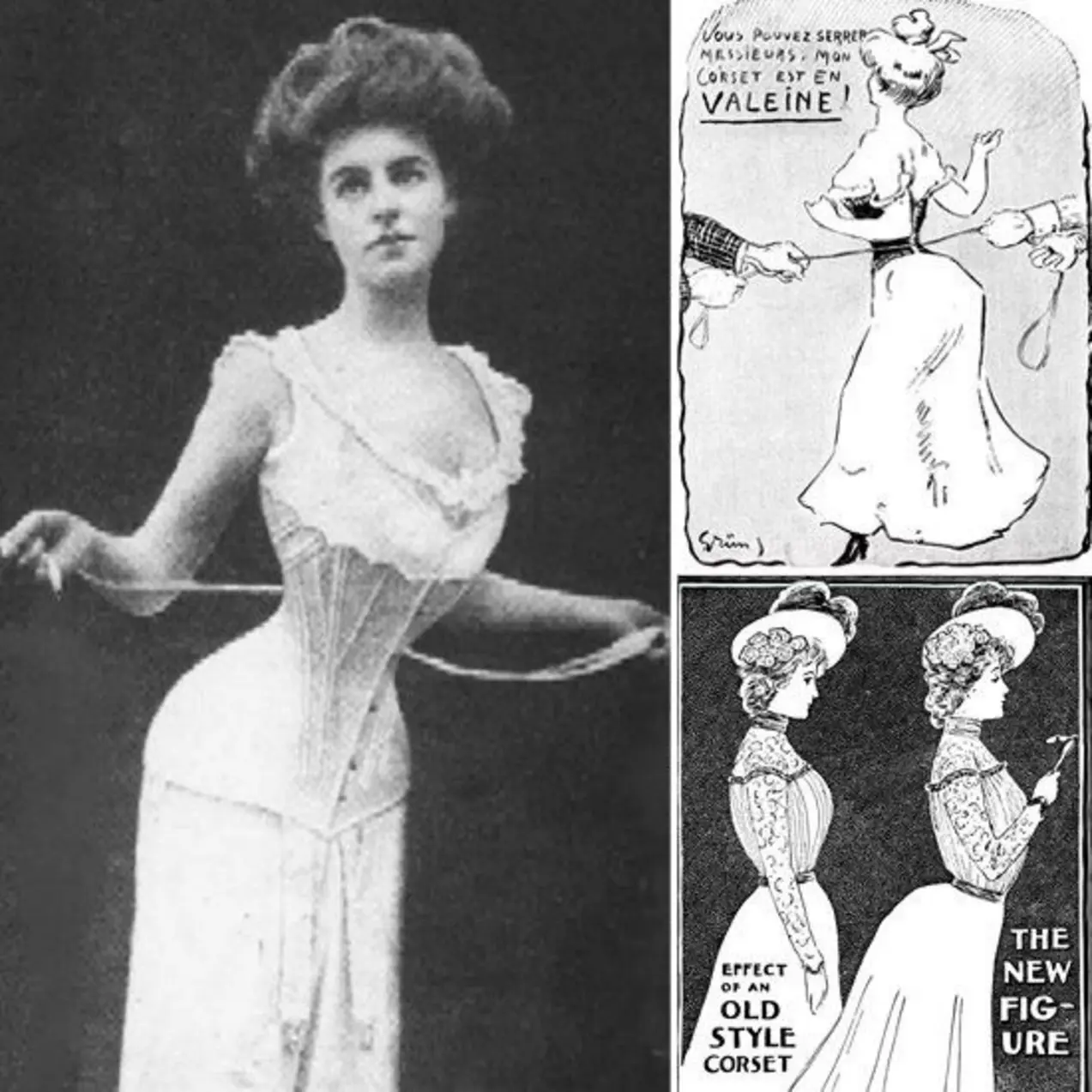

The hourglass silhouette refers to a body shape defined by a balanced bust and hips with a distinctly cinched waist, a form historically achieved through corsets, tailoring, and now modern hourglass body-shaped clothing. The hourglass silhouette has existed as long as humanity yearned for idealized beauty. While the concept of emphasizing a narrow waist has ancient roots, in Greek statuary and Renaissance paintings, the deliberate pursuit of the hourglass as a fashion ideal surged in the Victorian era (mid to late 19th century).

This was the age of the corset, a structural garment that became the foundation of the hourglass figure. Women, particularly those in aristocratic and affluent circles, practiced tight-lacing to achieve the coveted “wasp waist.” Voluminous skirts, supported by crinolines and later bustles, combined with padded bodices, were meticulously crafted to exaggerate the contrast between tiny waists and expansive busts and hips. A 19th-century corset could reduce a waistline by 4 to 6 inches, a feat documented in fashion plates and social commentary of the time. Though often criticized for its restrictive nature, the corset reigned supreme as a symbol of refinement, social standing, and theatrical femininity.

By the 1950s, Christian Dior’s New Look revived and modernized the hourglass silhouette. His Spring 1947 collection featured skirts with a 21-inch waist, sometimes padded to accentuate hips and bust, bringing a dramatic sense of curve back into post-war fashion. It was a triumph of glamour and marketing: sales skyrocketed, with some Dior skirts retailing at the equivalent of $1,500 today.

In contemporary culture, the hourglass has been synonymous with star power. Victoria Beckham, Lindsay Lohan, Nicki Minaj, and the Kardashians—each experienced their “hourglass era.” In the late 2000s and early 2010s, bodycon and bandage dresses weren’t mere trends—they were fashion obsessions. Every red-carpet appearance became a study in sculpted perfection: cinched waists, amplified curves, and maximum confidence.

This era marked the “golden age of the bombshell.” To wear an hourglass dress was not just to embrace glamour but to embody power. It hugged, lifted, shaped, and celebrated the body—offering its wearer a sense of fierce, liberated femininity.

Few cinematic figures embody the hourglass as viscerally as Margot Robbie’s Naomi Lapaglia. In The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), costume designer Sandy Powell turned fashion into psychological armor. Robbie’s Naomi enters in tight, body-hugging designs by Hervé Léger, Azzedine Alaïa, and Versace.

The iconic blue bandage dress by Hervé Léger exemplifies the principle: designed by Hervé Peugnet, its strips of elastic fabric sculpt the body into a living, breathing hourglass. In another key scene, Naomi wears a hot pink Alaïa bodycon dress, merging seduction with negotiation. Alaïa—“King of Cling”—designed not to conceal, but to elevate. His precision tailoring compressed waists, lifted curves, and created the archetype of 1990s glamour on screen.

Powell’s costuming tracked Naomi’s evolution, moods, and power plays, turning garments into visual metaphors. The film offered a cinematic resurrection of the hourglass, demonstrating that body-first luxury can be a statement of control, sophistication, and unapologetic femininity.

Designers continue to honor and reinterpret the hourglass. Hervé Léger by Max Azria’s Spring 2009 Ready-to-Wear collection is a landmark. Known for the bandage dress—a direct descendant of the hourglass ideal—the collection pushed the silhouette to hyper-real extremes. Strips of elastic fabric hugged bodies with architectural precision, creating waists that appeared impossibly narrow, while shoulders were structured to emphasize curves. The palette—black, crimson, navy, metallic, and nude—highlighted the body’s natural lines, and innovative insets of exotic skins elevated the texture.

Similarly, Roberto Cavalli’s Spring 2003 collection celebrated maximalist glamour. His ensembles—from silk cheongsams to patent leather mini dresses with dragon motifs—achieved the hourglass through corsetry and meticulous cut, amplifying the body while blending sensuality with architectural drama. Cleavages, padded hips, and bias-cut silk rendered the female form both theatrical and empowered, demonstrating that bold luxury and engineered allure could coexist.

Sculpted by centuries and refined by craft, the hourglass remains an intimate architecture of power. It signifies a woman who commands attention through unshakable confidence, not display. Each gesture is amplified by the silhouette’s elegance—a nod to those who understand that true extravagance lies in the perfection of line and the whisper of exquisite fabric.

In an era of social-media chaos, the hourglass retains discipline: it does not bend to algorithms or trends. For the modern woman, it is a second skin of intention, a symbolic aesthetic signature.

The contemporary hourglass is architectural poetry: sharp shoulders balanced with full hips, invisible boning or masterful tailoring shaping the waist, plunging necklines framing the décolletage, and skirts flowing yet precisely sculpted. It is both empowerment and adornment—a rare, flawless diamond in sartorial form.

To wear a high-fashion hourglass silhouette is to embrace a luxurious ease as liberating as it is seductive. Across its historical and modern incarnations, this bombshell silhouette continues to express a woman’s inherent power and allure, inviting us all to indulge in its irresistible embrace.