From December 18, 1911, to early 1912, at Heinrich Thannhauser’s Moderne Galerie in Munich, a small yet incendiary exhibition quietly altered the course of modern art. The first Der Blaue Reiter Exhibition rejected academic realism and polite aesthetics, proposing instead that color, form, and line could function as direct conduits to inner life, spiritual truth, and emotional intensity.

From December 18, 1911, to early 1912, at Heinrich Thannhauser’s Moderne Galerie in Munich, a small yet incendiary exhibition quietly altered the course of modern art. The first Der Blaue Reiter Exhibition rejected academic realism and polite aesthetics, proposing instead that color, form, and line could function as direct conduits to inner life, spiritual truth, and emotional intensity.

December 18, 2025

From December 18, 1911, to early 1912, at Heinrich Thannhauser’s Moderne Galerie in Munich, a small yet incendiary exhibition quietly altered the course of modern art. The first Der Blaue Reiter Exhibition rejected academic realism and polite aesthetics, proposing instead that color, form, and line could function as direct conduits to inner life, spiritual truth, and emotional intensity.

When the first Der Blaue Reiter arrived in Munich, it arrived without manifesto-like certainty or stylistic uniformity. Instead, it presented a shared conviction: that art should move beyond surface appearances and speak to deeper, often invisible realities. Organized at Heinrich Thannhauser’s Moderne Galerie, the show became a decisive rupture from the conventions dominating early twentieth-century European painting.

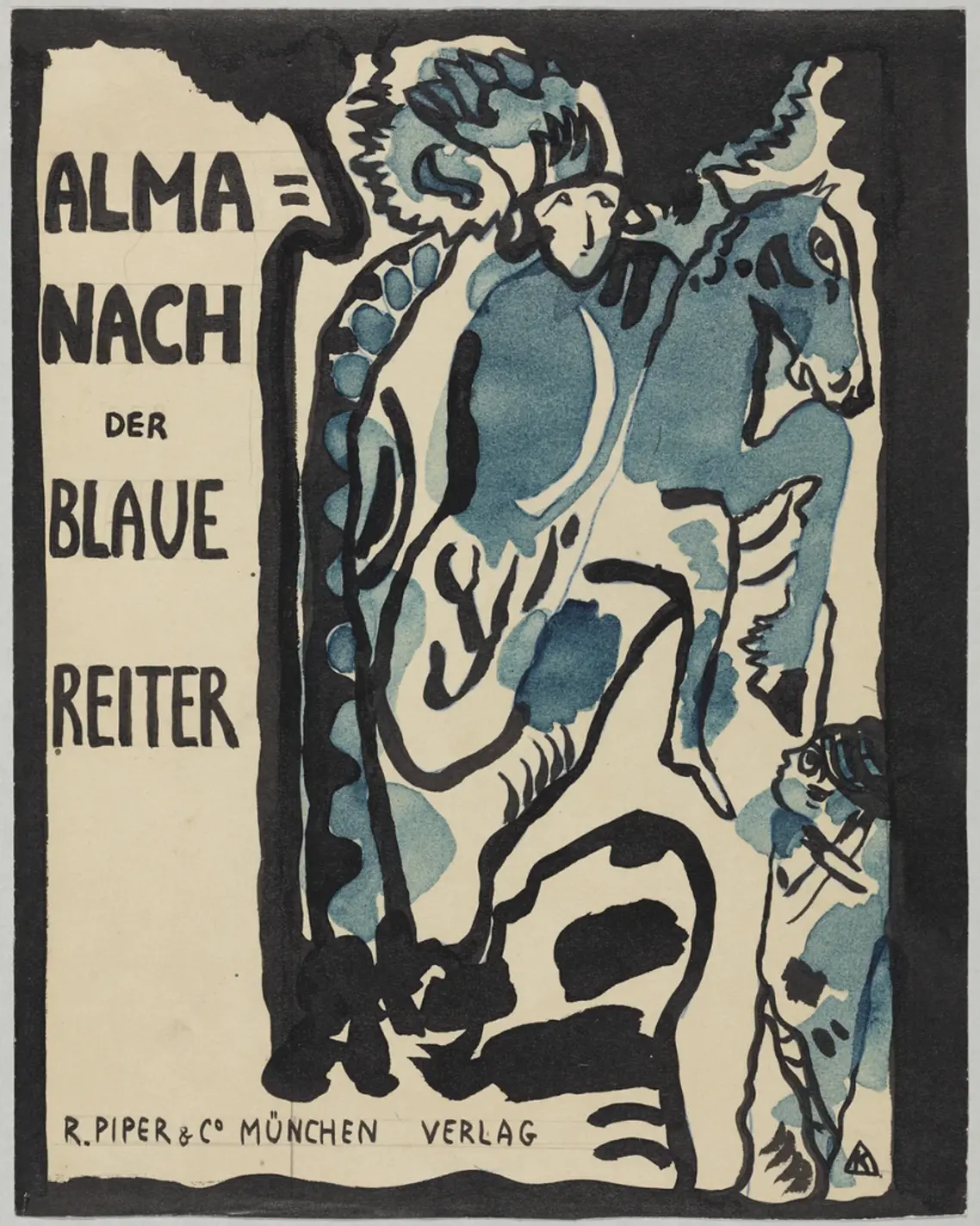

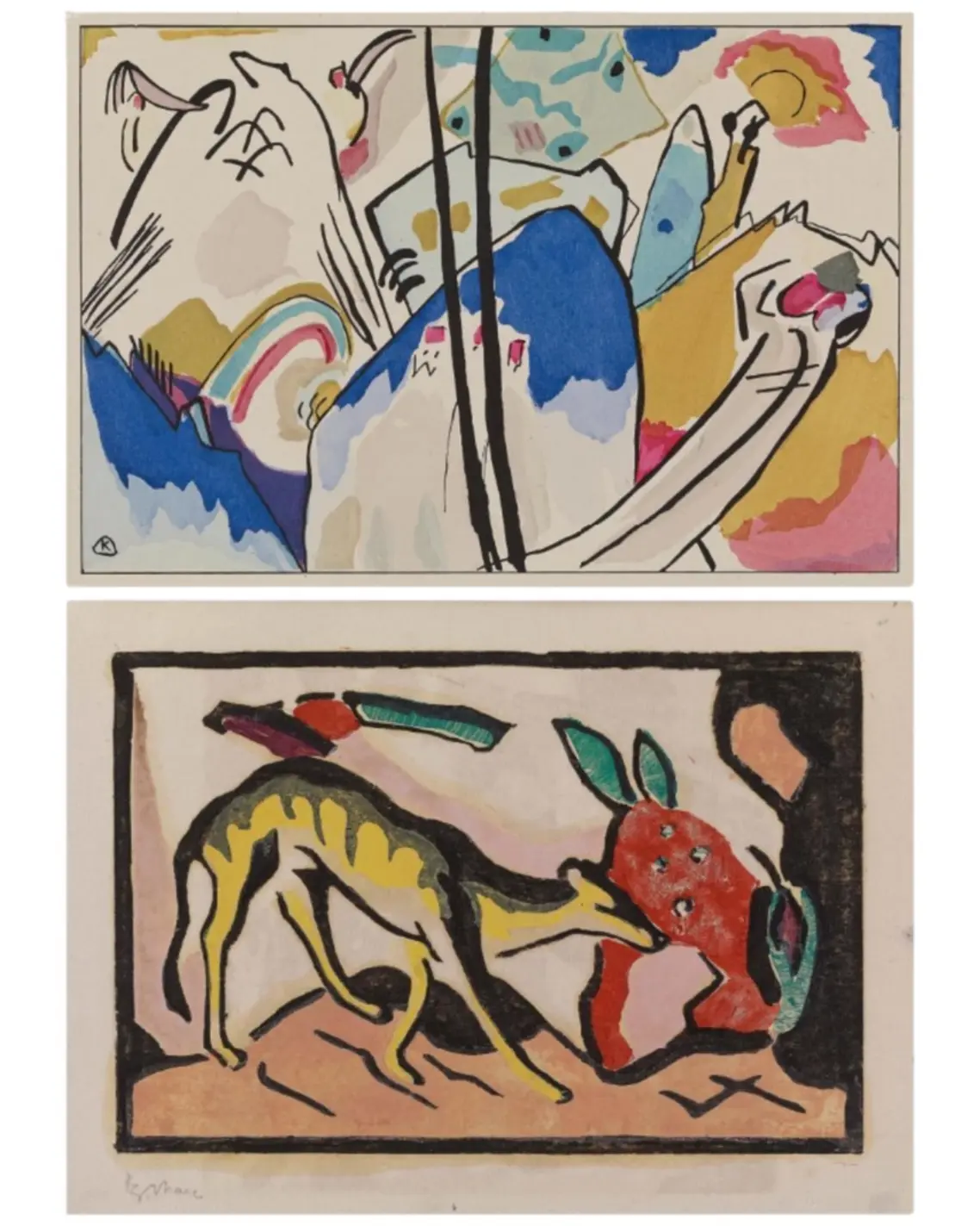

Led by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, Der Blaue Reiter functioned as an open constellation rather than a fixed group. Its artists were bound by spiritual inquiry rather than technique. Blue symbolized transcendence, while the rider evoked movement, freedom, and the idea of art as a journey rather than a destination.

The exhibition brought together works by Kandinsky, Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Alexej von Jawlensky, and Paul Klee. Across the gallery walls, traditional perspective dissolved, colors intensified into emotional signals, and animals and landscapes became vessels of moral and metaphysical meaning. Representation loosened its grip as abstraction began to assert itself as a legitimate language.

Audience reactions ranged from fascination to outright rejection. To many critics, the work appeared naïve or chaotic, yet this very refusal of refinement was the point. The exhibition challenged the idea that art existed to please the eye, proposing instead that it should awaken the soul.

Its impact extended beyond the gallery. In 1912, Kandinsky and Marc expanded the movement’s philosophy through The Blue Rider Almanac, aligning modern painting with folk art, music, and non-Western traditions. Though short-lived, the first Der Blaue Reiter exhibition remains a foundational moment, one that redefined modern art as an act of inner necessity rather than external imitation.