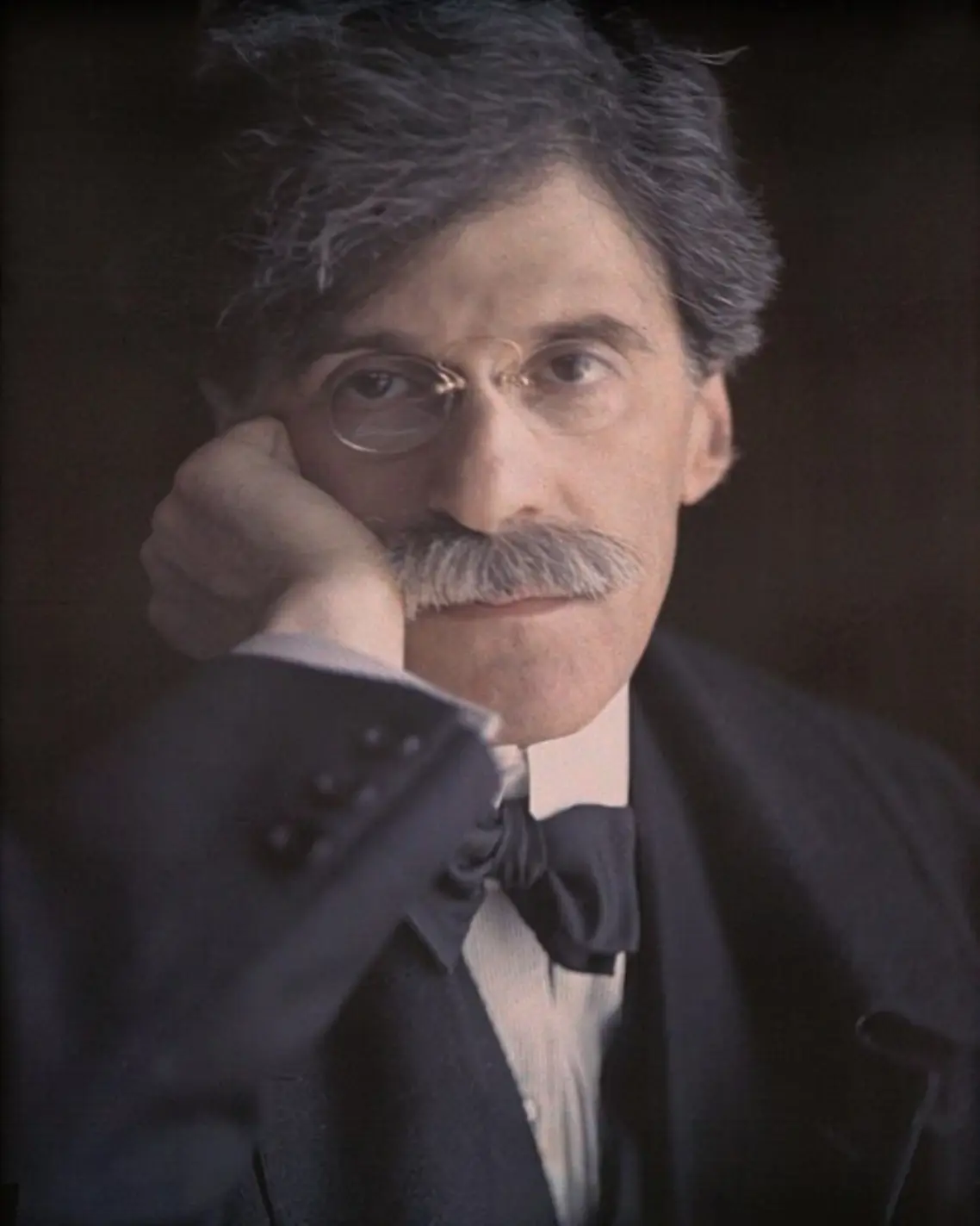

On January 1, the history of modern photography quietly celebrates one of its architects: Alfred Stieglitz.

On January 1, the history of modern photography quietly celebrates one of its architects: Alfred Stieglitz.

January 1, 2026

On January 1, the history of modern photography quietly celebrates one of its architects: Alfred Stieglitz.

Celebrating the birthday of Alfred Stieglitz means reckoning with a figure as polarizing as he was foundational. Stieglitz did not merely elevate photography into the realm of fine art; he policed its borders. His influence shaped what counted as modern, who was allowed into the canon, and which visions were amplified or erased. Genius and control lived uncomfortably close in his orbit.

Stieglitz’s crusade for photography’s legitimacy often read as cultural gatekeeping. Through Camera Work and his galleries, he curated taste with near-total authority, positioning himself as arbiter of modern vision. The artists he championed prospered; those he dismissed struggled for oxygen. His insistence on “straight photography” later in life hardened into doctrine, sidelining alternative experiments and reinforcing a singular modernist narrative that mirrored his own evolving preferences.

Even his most celebrated images carry friction. The Steerage is praised for its modernist clarity and social tension, yet critics have long argued that its politics stop at composition. The image frames class division without challenging it, turning lived inequality into formal elegance. Stieglitz’s modernity often aestheticized upheaval rather than confronting it, a move that won acclaim while softening critique.

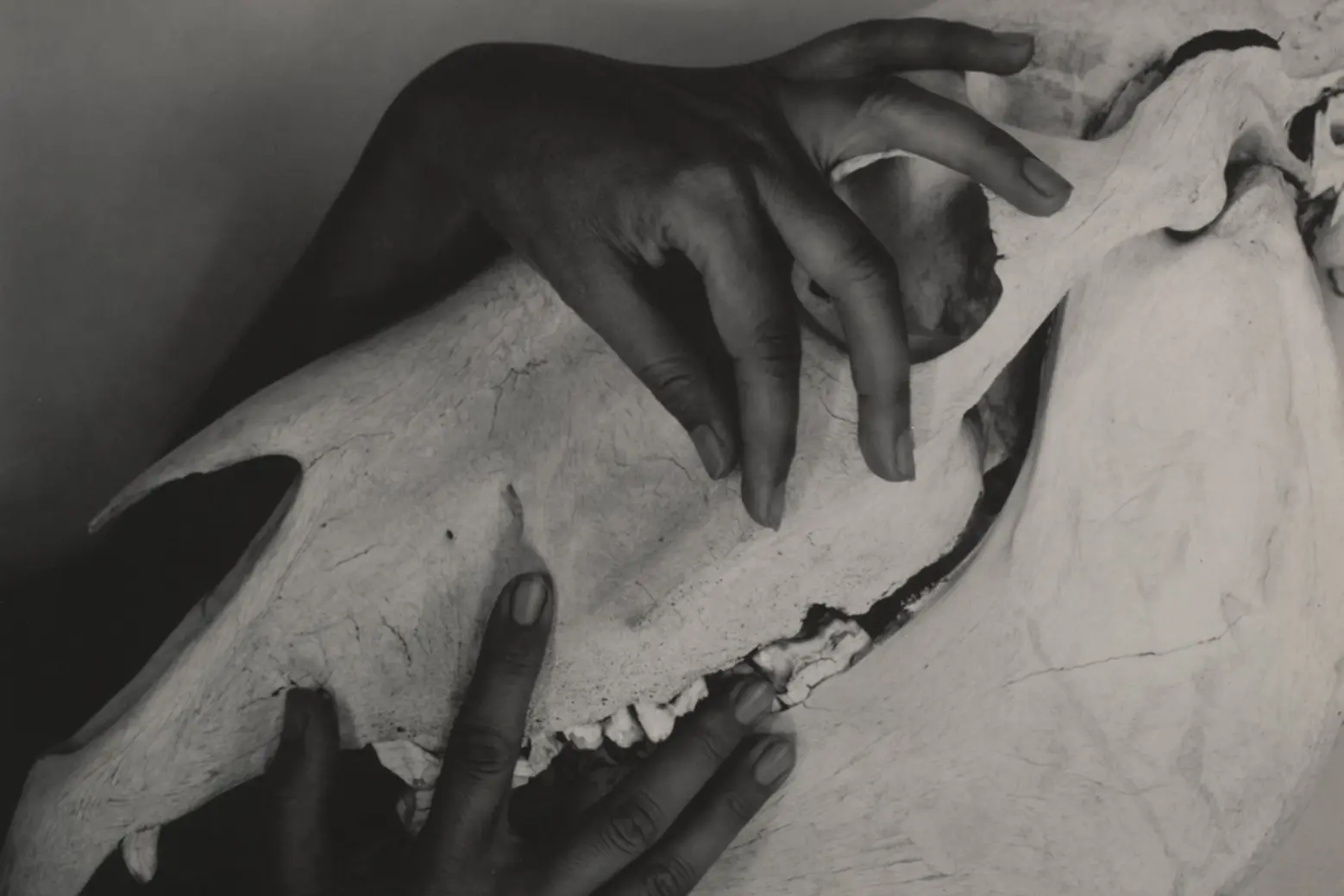

The controversies sharpen when the story turns to Georgia O'Keeffe. Their relationship, frequently romanticized as a meeting of equals, was also a study in power. Stieglitz photographed O’Keeffe relentlessly, crafting a public persona that at times threatened to eclipse her authorship. His exhibitions and writings framed her work through his gaze, shaping how critics and collectors learned to read her paintings. O’Keeffe would later distance herself, both geographically and artistically, from his gravitational pull, a move many interpret as reclamation rather than retreat.

The Equivalents series further complicates the myth. These cloud photographs, hailed as early photographic abstraction, also signal a retreat into personal metaphysics at a moment when American art faced urgent social questions. Stieglitz chose inward transcendence over outward confrontation, privileging emotional purity while the world fractured around him.

Remembering Alfred Stieglitz means holding two truths at once. He was indispensable to photography’s rise and instrumental in narrowing its conversation. On his birthday, the celebration feels incomplete without critique. His legacy endures precisely because it provokes, asking whether modernism’s greatest champions were also its most limiting architects.