On November 29, 1940, Diego Rivera completed what many consider the most ambitious and generous mural of his career: Pan American Unity.

On November 29, 1940, Diego Rivera completed what many consider the most ambitious and generous mural of his career: Pan American Unity.

November 24, 2025

On November 29, 1940, Diego Rivera completed what many consider the most ambitious and generous mural of his career: Pan American Unity.

Painted live before thousands at the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island, the fresco stands as one of the greatest artistic statements about cultural exchange ever created, an enormous, beating heart made of pigment, history, and hope.

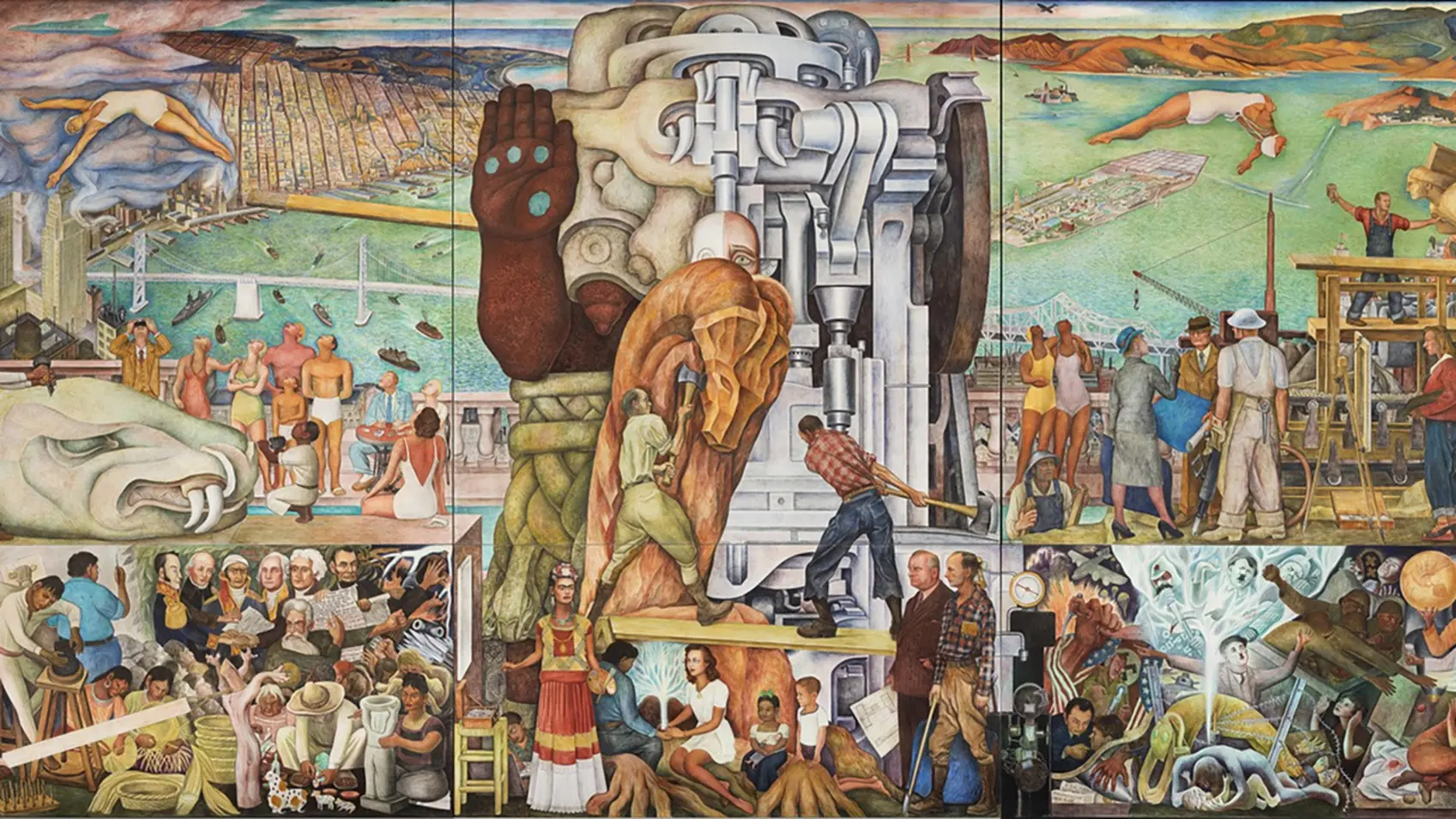

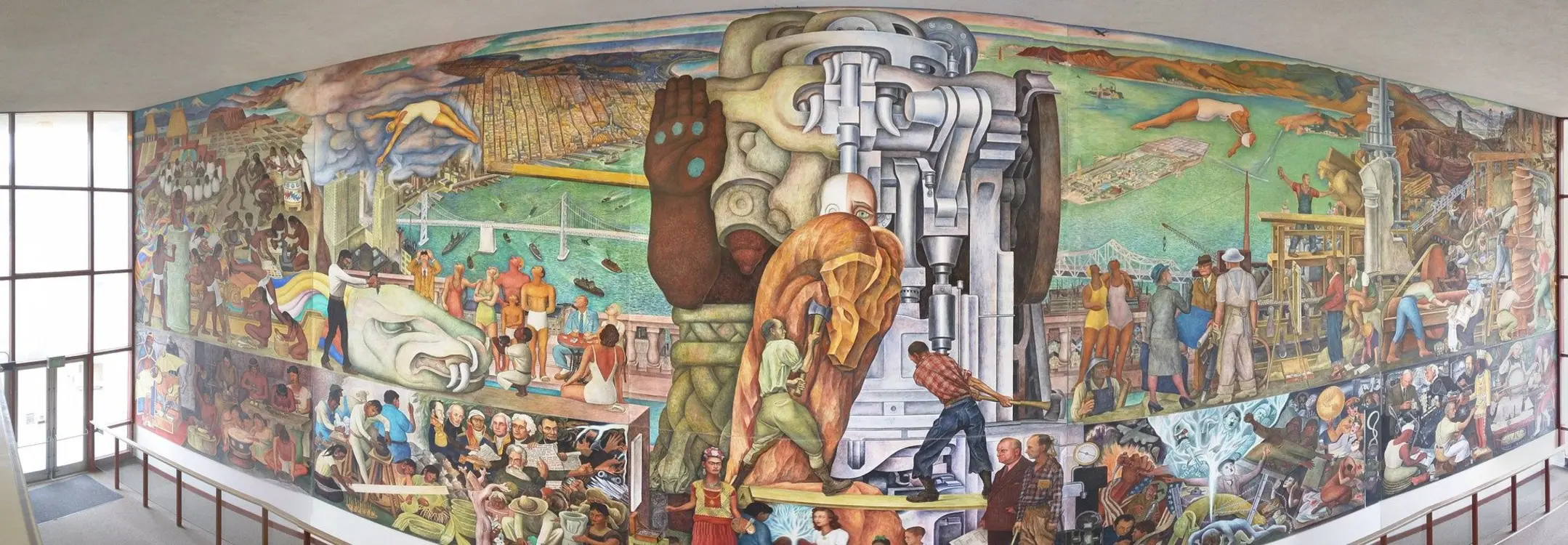

Rivera worked on the 74-foot-wide, 10-panel fresco publicly, turning the act of creation into performance. Visitors watched him mix pigments, sketch new figures, erase ones he disliked, and expand the composition beyond its original scope. By the time he finished on 29 November, the mural had become a sweeping visual manifesto weaving together: Indigenous mythologies and modern industry, inventors, artists, liberators, and everyday citizens and the machinery of progress alongside the poetry of the past. Rivera called it “the fusion of the artistic expression of the two Americas.” It was an argument made in color: that creativity, not conquest, should guide the hemisphere’s relationship.

What makes the mural so alive is the tension inside it. Rivera painted in 1940, on the eve of global war, amid rising fascism, and in a United States wrestling with its own identity. Rather than retreat into myth or romanticism, Rivera depicted both the violence and the promise of modernity.

He placed artists like Frida Kahlo beside engineers, ancient deities beside aircraft designers. He portrayed the rise of dictators as sharply as he celebrated cultural renewal. The result is a mural that feels less like a static artwork and more like a living debate.

One of Rivera’s favorite inclusions was an image of sculptor Dudley Carter, carving wood directly on the exposition grounds. “Here,” Rivera said, “is the meeting of North American craftsmanship and Mexican tradition.” It symbolized everything he believed the mural stood for.

When the mural was finished on 29 November, Rivera imagined it would live permanently in a public San Francisco space. Instead, it would spend decades hidden, stored, or partially displayed, until a new wave of appreciation restored it to cultural prominence.

Today, Pan American Unity is celebrated as Rivera’s last and largest mural completed in the U.S, a blueprint for cross-cultural creativity, a historical document of American industry, politics, and artistic power and a reminder that unity, at its best, is built through exchange, not erasure. More striking still, the mural feels prophetic. Its themes: democracy under threat, cultural collaboration, the tension between technology and humanity, speak as clearly in 2025 as they did in 1940.

Rivera believed art could tell the truth and still offer hope. Pan American Unity is both: a mirror of the world and a map toward something better. Eighty-four years after its completion, it continues to challenge us, inspire us, and call us to look beyond borders toward a shared, more imaginative future.