Imagine a designer who rarely appeared in public, refused interviews, and then quietly disappeared from the fashion world without a word of farewell. Though he departed the runway over 15 years ago, Martin Margiela remains an undying icon, pioneering deconstruction fashion, upcycling, and a total rejection of fashion's inherent vanity. His work sits at the core of avant-garde fashion and the modern anti-fashion impulse: the belief that clothing can question power, authorship, and taste itself, instead of flattering it.

Imagine a designer who rarely appeared in public, refused interviews, and then quietly disappeared from the fashion world without a word of farewell. Though he departed the runway over 15 years ago, Martin Margiela remains an undying icon, pioneering deconstruction fashion, upcycling, and a total rejection of fashion's inherent vanity. His work sits at the core of avant-garde fashion and the modern anti-fashion impulse: the belief that clothing can question power, authorship, and taste itself, instead of flattering it.

October 2, 2025

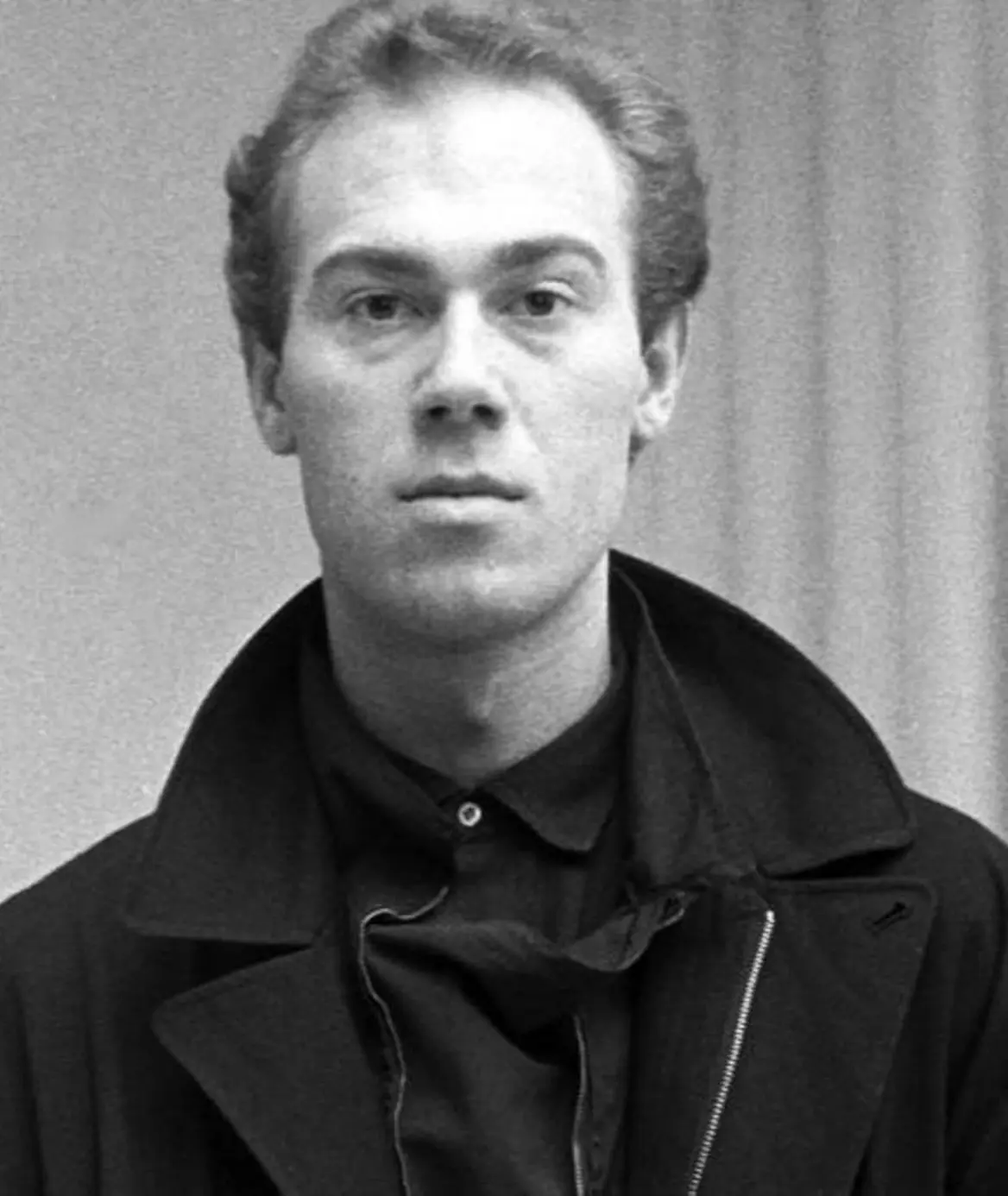

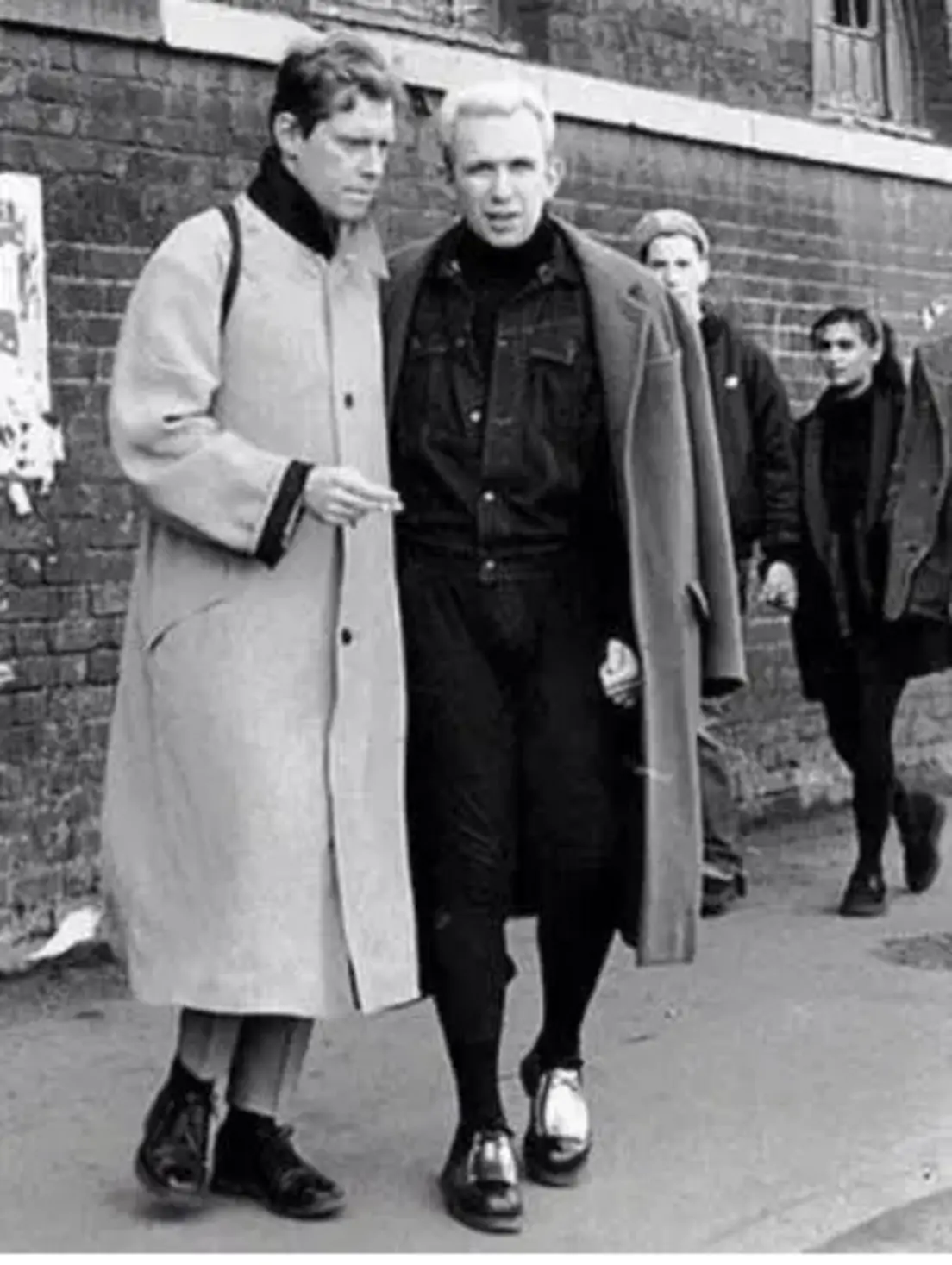

Few can deny Martin Margiela is one of the most eccentric and elusive figures in contemporary fashion history. Even while working as Jean Paul Gaultier's right-hand man, and later upon establishing his own label in the 1980s, he deliberately eschewed getting caught in the media spotlight. He feared that the cult of personality surrounding artists would overshadow the intrinsic value of quality design. He consistently refused interviews, remained out of sight, and even in the documentary about himself, one only hears the voice of the pioneering Belgian designer as he refers to himself in the first-person plural "we." This was his powerful declaration: "No one represents Maison Martin Margiela; it is a collective."

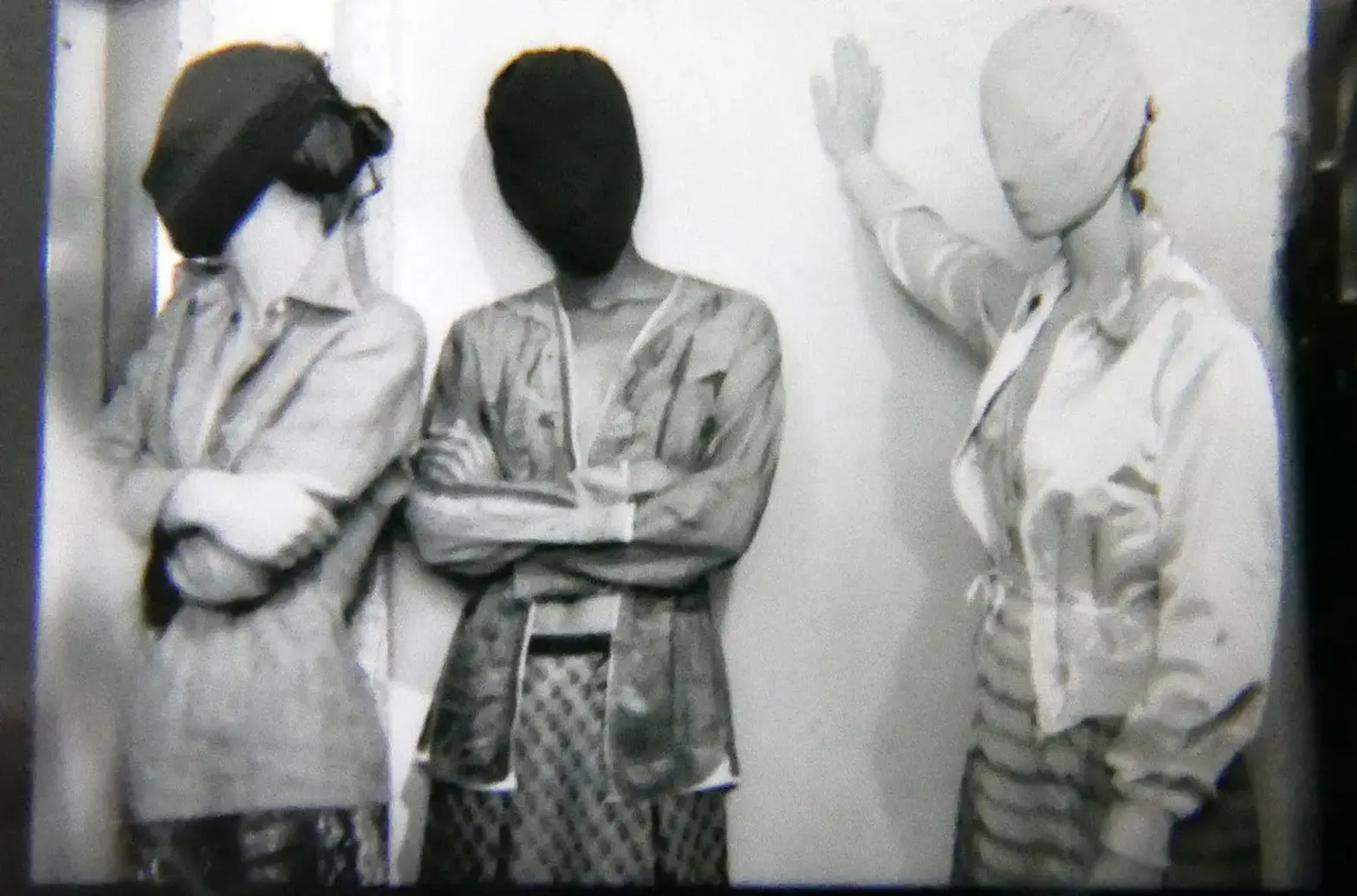

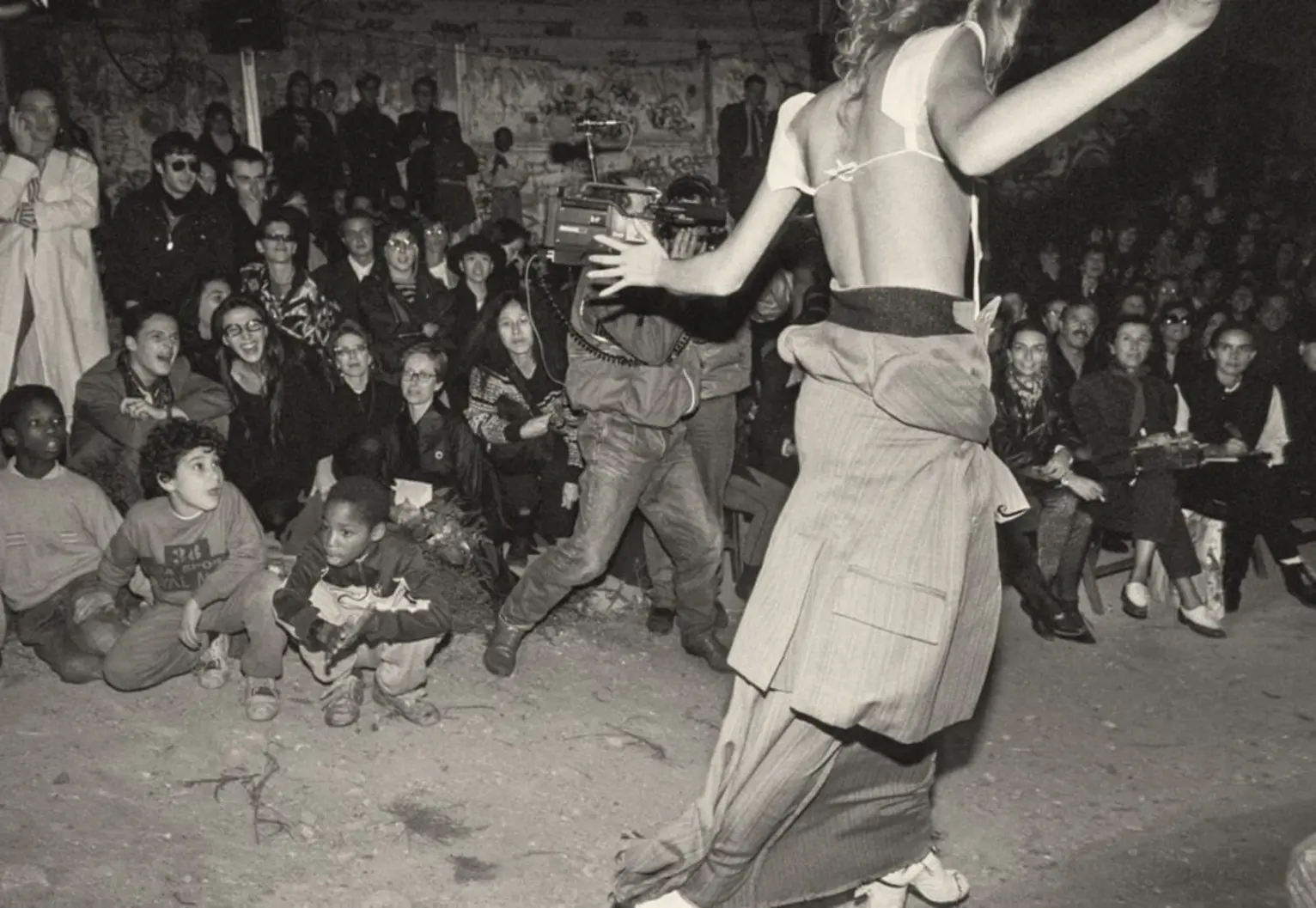

This philosophy of anonymity was further expressed through his radical choice of show venues for his creations: primitive warehouses, underpasses, or abandoned subway stations. Models were sometimes non-professionals, their faces obscured by fabric layers or bizarre makeup. There were no spotlights, no designated celebrity seats, and no mention of the name Martin Margiela, allowing only the designs of Martin Margiela to be presented.

After years of operation, Martin Margiela abruptly disappeared from his eponymous label in 2009. Without official announcement or farewell, he withdrew from the fashion industry as silently as he had lived within it. Yet, Martin Margiela never lost his revered status among fashion devotees. He paved the way and planted the seeds for the "anti-fashion" movement - a rejection of surface-level beauty in favor of deeper exploration in the materiality, structure, and inherent message of each garment. Designers like Demna Gvasalia (Vetements, Balenciaga) and Phoebe Philo are living testaments to his enduring influence.

Fashion, under Martin Margiela's hand, was never merely about clothing. He viewed garments as objects to be explored, dismantled, and redefined. Margiela was among the first designers to introduce the philosophy of deconstruction fashion into fashion. This approach visibly manifested in his designs by exposing internal structural elements that are typically concealed, such as inside-out seams, exposed stitching and unfinished hems.

These characteristics not only broke traditional construction norms but also led to another core facet of Margiela's design language: imperfection (or incompleteness). This imperfection was not a flaw or a tailoring error but a deliberate and challenging sartorial statement. Instead of striving to conceal or meticulously finish every detail according to conventional standards, Margiela embraced and fully exploited imperfection. He found authentic beauty in fragments of broken ceramic plates reassembled into a vest, or in worn-out leather gloves. When details like frayed edges or wrinkled fabrics were retained, they were not merely design elements but embodied the garment's formation, the raw honesty of the material, and a beauty free from any polished, artificial façade

Looking at the Margiela Spring/Summer 1997 collection, one is not only amazed by his spirit of recycling and original creativity, but also by how explicitly he demonstrated this philosophy. Prominent designs, such as the Stockman coat, crafted from raw linen with unfinished edges, and use of staples instead of traditional stitching, exemplified Margiela's deconstructionist philosophy. He also audaciously repurposed fabric scraps, exposed linings, and printed technical notes directly onto the fabric, creating a bold interplay between perfection and imperfection.

For Margiela, materials were not merely tools but a medium for creative thought. Alongside deconstruction, Martin also deeply explored upcycling in his design approach, long before sustainable fashion went mainstream.

He possessed an unparalleled ability to transform seemingly worthless items into unique works of art. From old leather gloves becoming a jacket (Spring/Summer 2001), and shattered ceramic pieces forming a vest, to ordinary objects like champagne corks turning into necklaces, or garments upcycled from used plastic bags appearing on the runway as a narrative about material life. He even created coats from champagne bottle labels or dresses from old cassette tapes and hair combs, notably including a men's waistcoat made from hundreds of playing cards in the Margiela Artisanal collections, specifically the Artisanal Spring-Summer 2006 collection. He elevated what was considered refuse into symbolic haute couture.

His use of adhesive tape instead of traditional seams further exemplified his pioneering spirit in breaking all material conventions, elevating seemingly temporary elements into a contemporary aesthetic language.

With Martin Margiela's design language, differences seemed to matter more than beauty itself. His creations reflected a vision that stood apart from the rest of the fashion world. For Margiela, clothing did not have to be graceful, nor could it be confined by conventions set by others. Paradoxically, while he chose to remain hidden from the public eye, his designs chose to stand out, carrying a fierce spirit of rebellion.

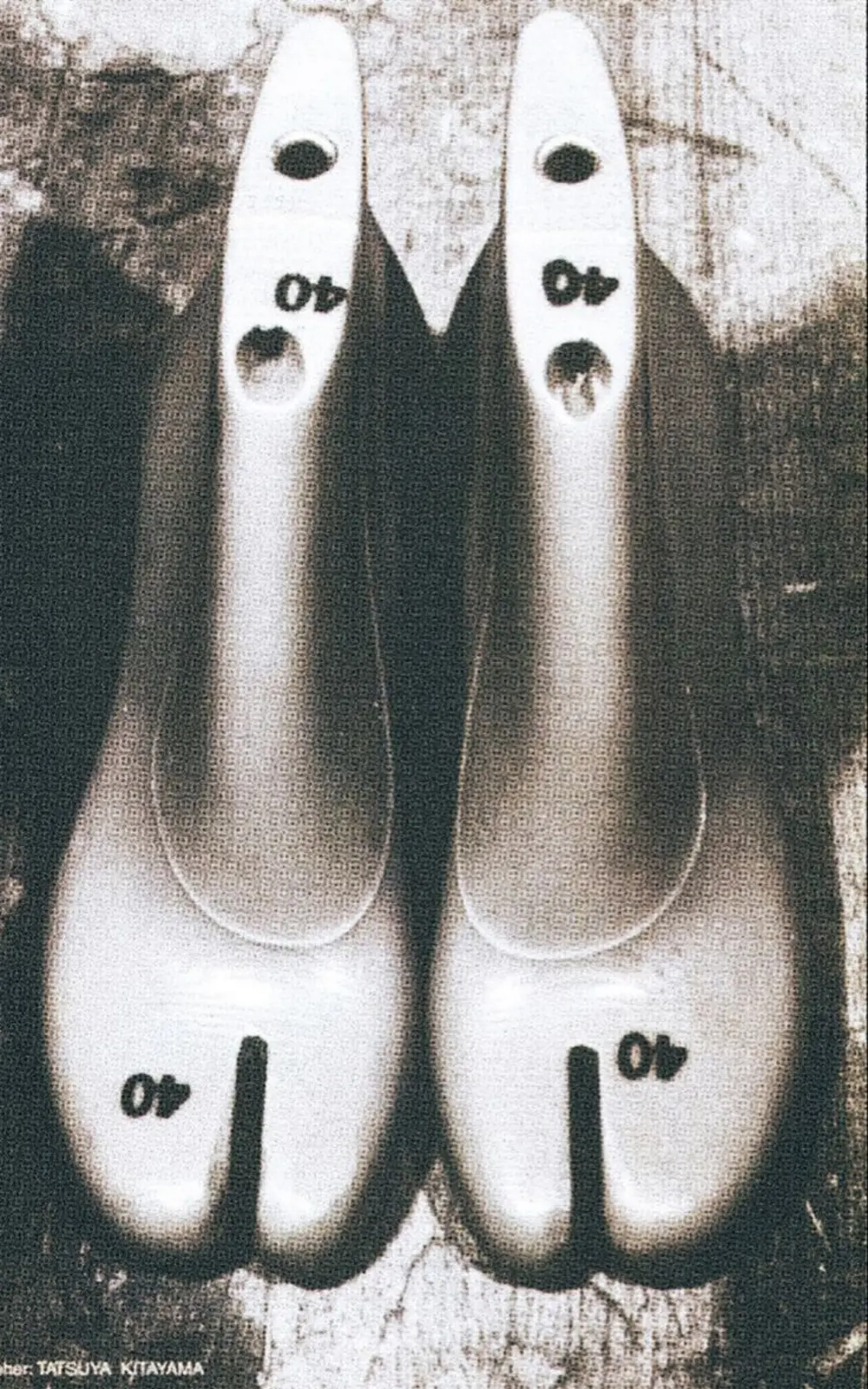

This spirit came to life most vividly with the debut of the Tabi shoe - mockingly nicknamed "pig's hoof" by early critics. If Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons is synonymous with challenging deconstructed designs like the "Lumps and Bumps" collection, Hermès with its legendary Birkin bag, or Louis Vuitton with its iconic Monogram pattern, then the legacy of Martin Margiela is inextricably linked to the Tabi.

These shoes can be controversial for those unwilling to embrace their unconventional shape, but for fashion enthusiasts, the Tabi is an icon, and furthermore, has become the unmistakable signature of the French luxury fashion house Maison Margiela. The Tabi's origins trace back to 15th-century Japan, initially as split-toe socks designed to be worn with traditional footwear like zori and geta. This split-toe design was believed to promote balance and a clear mind. By the early 1900s, these socks evolved into Jika-tabi - a type of shoe favored by manual laborers, even making an appearance at the Boston Marathon in 1951.

The most significant turning point for the Tabi, transitioning it from tradition to high fashion, was in 1988. Fascinated by the Tabi, Martin Margiela first introduced them on the runway during Maison Margiela's debut collection. He deliberately amplified its defiance in his first Maison Margiela runway show: models in Margiela Tabi boots dipped in bright red paint left split-toe footprints like trails of blood on the runway, a daring, unforgettable work of conceptual art that shook the fashion establishment. A year later, in the Fall/Winter 1989 show, the Tabi reappeared, solidifying its place.

Over time, the Tabi transcended the realm of footwear, becoming a symbol of Margiela’s anti-conformist ethos. It has appeared in countless iterations, from knee-high boots to ballet flats, loafers, and Mary Janes, transforming classic silhouettes into something unexpected and boldly new. The continued reinvention of Margiela Tabi boots proves the idea was never novelty. It was a thesis.

Despite being labeled "ugly" or "bizarre," the Tabi shoe is now celebrated as avant-garde, bold, and fashionable, embraced by countless global celebrities. Figures like Chloë Sevigny, who wore Tabis since the 90s, or more recently Zendaya, Emma Chamberlain, Dua Lipa, and Cardi B, have confidently incorporated Tabis into their unique personal styles. Notably, in 2023, Tabi Shoes surged in popularity across social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, transforming a once "hard-to-approach" design into something oddly desirable. The Tabi's widespread appeal once again proves that fashion, under Margiela's hand, was never merely about dressing; it was always a cultural act, a form of counter-statement, and a declaration of how we choose to exist in the world.

Despite choosing to retreat from the public eye, Martin Margiela never lost his immutable standing in the hearts of fashion enthusiasts. He was not merely a designer but a philosopher, a trailblazer who initiated and cultivated a new generation of anti-fashion statements. This movement challenges superficiality, encouraging a deep dive into the materiality, structure, and true message of each garment.

Leading designers today serve as living testaments to Margiela's profound and lasting impact. Demna Gvasalia (Vetements, Balenciaga), for instance, with his deconstructionist approach, exaggerated proportions, and redefinition of everyday wear, often seen in Vetements collections where he elevated familiar items into challenging high fashion designs. Similarly, Phoebe Philo, with her minimalist aesthetic, focuses on garment essence, and preference for asymmetrical structures and comfort in her Céline collections, reflects a dialogue with Margiela's philosophy on form and bodily liberation.

In a world where designers are idolized, brands chase trends, and fashion is consumed by commercialism, Margiela chose to step back, allowing clothes to speak for themselves. And it is precisely that silence that became the most powerful voice, shaping deconstruction fashion and avant-garde fashion into a timeless legacy that continues to resonate to this very day, from Margiela Artisanal collections to the lasting cult of Margiela Tabi boots.