A kiss seems like the simplest gesture in the world. Yet, in the art world, painters have treated kisses in paintings as a technical dare and a philosophical problem.

A kiss seems like the simplest gesture in the world. Yet, in the art world, painters have treated kisses in paintings as a technical dare and a philosophical problem.

February 10, 2026

Two faces move closer, time speeds up, breath changes, a whole emotional weather system arrives in a second. Painting, meanwhile, lives in slow time. It pauses the moment and asks a still image to carry heat, consent, suspense, tenderness, risk.

Across centuries, artists have used the kiss to say very different things: devotion, farewell, rebellion, memory, obsession, secrecy, comedy. Sometimes the lips touch. Sometimes the kiss stays just out of frame, hovering in a letter, a shadow, a doorway. Either way, the viewer becomes a witness. The room feels quieter. The air looks charged. Even paint seems to lean forward.

Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–1908) may be one of the most instantly recognizable kisses in paintings. Two figures kneel at the edge of a flowered meadow, wrapped in a single cloak that reads like a holy textile. Gold shimmers across the surface, less like a color than a climate: radiant, ceremonial, spellbound.

Klimt turns romance into ornament, and ornament into emotion. The man’s robe carries rectangular motifs, steady and architectural. The woman’s robe blooms with circles and flowers, softer, more cellular, like life repeating itself. Their bodies disappear into pattern, as if love dissolves the boundary between person and universe. The kiss becomes a portal: a private act rendered with the visual language of icons and mosaics, devotion expressed through gleam.

The brilliance also performs a clever trick. The gold sets the couple apart from everyday reality, creating a world that feels sealed, hushed, sacred. The meadow becomes stage, the cloak becomes curtain, and the kiss becomes the entire plot. In Klimt, a kiss looks like destiny made visible.

Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss (1859) arrives with a very different temperature. Here, the kiss belongs to Romanticism, yet it carries the taut energy of politics and departure. A couple embraces in a stone interior, half-lit, almost clandestine. The man leans in with urgency, one foot already finds a step, as if the body prepares for escape even while the mouth asks for one more second.

In nineteenth-century Italy, the painting became linked with the Risorgimento, the movement toward unification. Hayez stages passion as a coded message: love as a cover for loyalty, desire as a veil for history. The kiss reads like a vow made under pressure, the kind that turns sweet precisely because time feels scarce.

What makes it endure is its cinematic clarity. The viewer senses the before and after. The kiss marks a threshold: the room behind them, the world ahead of them, the instant that stitches those two realms together.

Marc Chagall’s The Birthday (1915) offers a kiss that floats — literally. In a modest room filled with domestic detail, Chagall bends impossibly through the air to kiss his beloved, Bella. A bouquet waits in his hand. The bodies curve like a ribbon. The scene feels playful, intimate, miraculously light.

Chagall paints love as a physics of its own. Emotion becomes lift. The ordinary space: The floorboards, wallpaper, window, stays grounded, while the lovers enter a separate logic where joy tilts the body away from gravity. The kiss becomes a small act with cosmic consequences: it rearranges the room, rewrites the rules, turns everyday life into a fable.

Part of the power comes from tone. Chagall avoids grandeur. He gives us a kiss in a room that looks lived-in, a love that grows out of daily reality and then gently transcends it. The result feels like the purest wish behind romance: to make life feel lighter, to make the world kinder, to make the air itself participate.

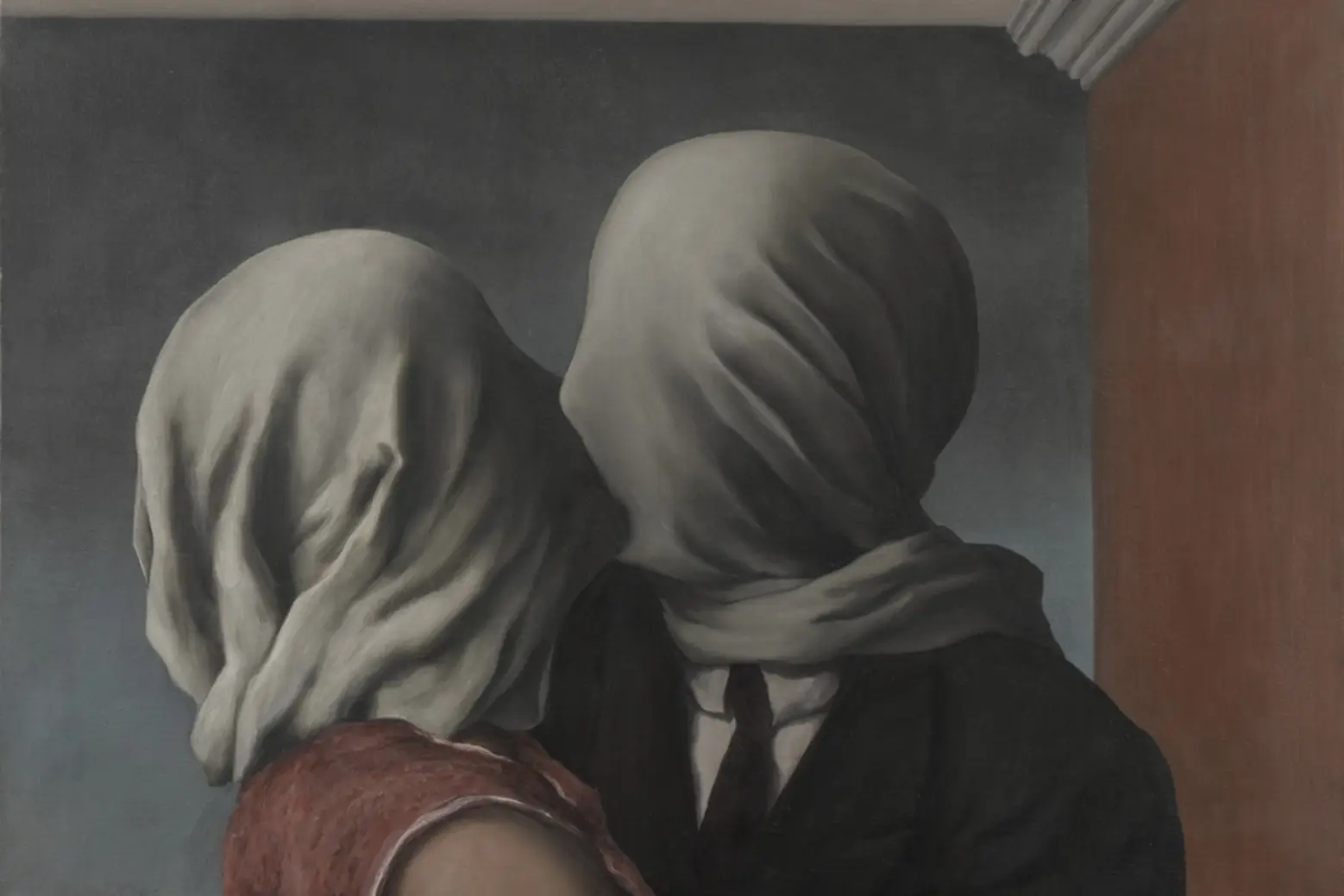

René Magritte’s The Lovers (1928) shows a kiss, yet fabric covers both faces. The cloth creates a paradox: intimacy and distance arrive together. The lovers tilt toward each other, as if seeking closeness, while the veil turns the kiss into an enigma.

Surrealism often works by shifting one familiar detail until everything feels strange. Magritte chooses the most human of gestures, then removes the part that usually carries recognition: the face. The kiss becomes anonymous, dreamlike, slightly unsettling. The painting asks questions rather than delivering answers. What does desire seek: a person, an idea, an absence? How does closeness feel when certainty slips away?

Magritte also reveals a truth about love’s theater. People often carry masks — social, personal, emotional. A kiss can feel like a removal of masks, or it can feel like two masks pressing together, tender and tragic at once. The Lovers keeps its secret, and that secrecy becomes its magnetism.

Edvard Munch painted The Kiss in the 1890s (a key version dates to 1897), and his approach feels psychological, almost spectral. A couple embraces near a window. Their faces blur together, as if the boundary between two identities melts. The room darkens around them, and the kiss becomes a kind of merging — beautiful, eerie, consuming.

Munch belongs to Symbolism and early Expressionism, where emotion shapes the image. Here, the kiss reads less like romance and more like transformation. Individuality softens. The lovers become one form, one shadow. Some viewers read it as union, others read it as surrender. That tension is exactly the point: love can feel like home, and it can feel like loss of self, sometimes both in the same breath.

The brushwork supports this mood. Edges dissolve. The painting favors atmosphere over detail, as if the kiss fogs the air. Munch makes the kiss feel inevitable, almost elemental, like night falling.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s In Bed: The Kiss (1892) moves the kiss into modern life. Two women embrace in bed, rendered with tenderness and immediacy. The scene feels observed yet gentle, like a moment glimpsed in soft morning light.

Toulouse-Lautrec had a gift for depicting intimacy without turning it into spectacle. The kiss here reads as affection, companionship, lived closeness. The composition stays tight. The viewer’s attention stays on the faces and the curve of bodies, the simple truth of two people sharing warmth.

In the context of late nineteenth-century Paris, the painting also carries social meaning. It grants dignity to a kind of love that society often pushed into shadows. The kiss becomes both personal and quietly radical: a declaration that tenderness deserves a place on the canvas.

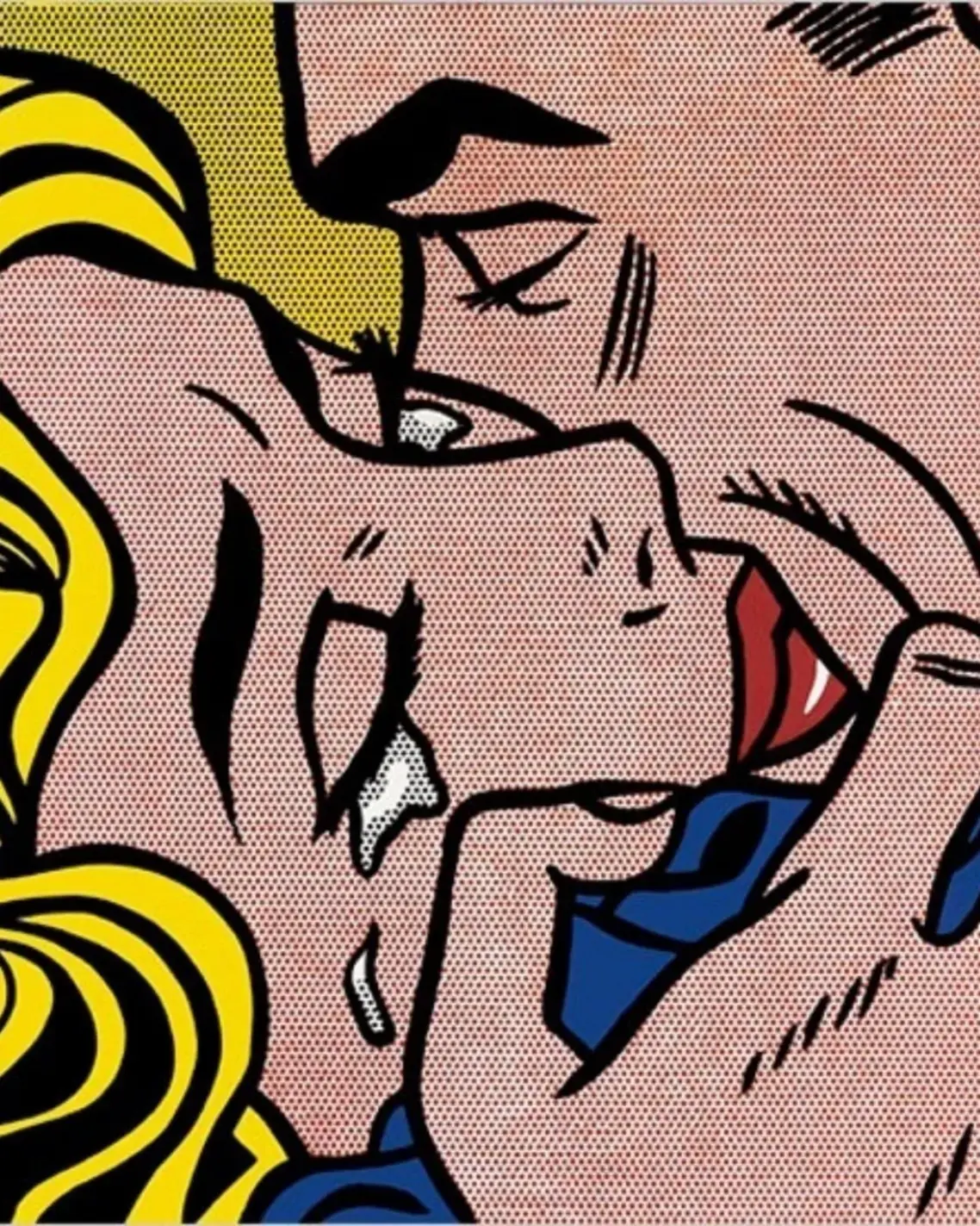

Roy Lichtenstein turned the kiss into pop iconography in works like Kiss V (1964). Here, romance comes through the language of comics: bold outlines, stylized features, melodrama condensed into a single frame. The kiss becomes graphic, immediate, almost audible.

Yet the work holds more than parody. Lichtenstein captures how mass media teaches people to perform emotion: the scripted swoon, the cinematic close-up, the moment designed for maximum impact. His kisses feel like cultural memory. Many viewers recognize the feeling of learning romance through images before living it through experience.

In pop art, the kiss becomes a symbol traded at high speed. The irony and the sincerity coexist. The painting can feel glamorous, funny, slightly tragic. A kiss becomes a product, a headline, a fantasy. The canvas becomes a mirror reflecting how love circulates in modern culture.

Kisses in real life disappear as soon as they happen. Kisses in paintings last. It stays available, repeating its emotion each time someone looks. Artists understand this, and they use the kiss as a way to trap the most fleeting part of love inside pigment and composition.