From graffiti-splashed monograms to Jeff Koons’ Mona Lisa, Louis Vuitton has long blurred the line between fashion and fine art. But beneath the polka dots, cherries, and neon graffiti lies a calculated empire-building strategy: turn every bag into a canvas, and every collection into a cultural event.

From graffiti-splashed monograms to Jeff Koons’ Mona Lisa, Louis Vuitton has long blurred the line between fashion and fine art. But beneath the polka dots, cherries, and neon graffiti lies a calculated empire-building strategy: turn every bag into a canvas, and every collection into a cultural event.

September 25, 2025

From graffiti-splashed monograms to Jeff Koons’ Mona Lisa, Louis Vuitton has long blurred the line between fashion and fine art. But beneath the polka dots, cherries, and neon graffiti lies a calculated empire-building strategy: turn every bag into a canvas, and every collection into a cultural event.

Louis Vuitton has never been content to simply sell luxury. The maison, founded in 1854 as a trunk maker, quickly realized that luggage could carry not only belongings but also cultural cachet. By the 1920s, Gaston-Louis Vuitton, grandson of the founder, invited artists to design store windows—a move that set the brand apart from its rivals. Art was not decoration; it was a statement of identity. Vuitton wanted to be not another luxury brand but a masterpiece in motion.

That philosophy has only deepened. Today, Louis Vuitton does not just flirt with art—it courts, sponsors, exhibits, and marries it. Fashion becomes the gallery, the bag becomes the canvas, and the buyer becomes the collector.

The turning point came in 1997, when Marc Jacobs took over as creative director. Young, brash, and unafraid of sacrilege, Jacobs dared to treat the sacred Monogram canvas like a blank wall in downtown New York.

In 2001, he invited Stephen Sprouse to graffiti the LV logo. The result was scandalous, thrilling, and unforgettable: neon paint scrawled across Speedy and Keepall bags. It was punk colliding with Parisian polish. The collection sold out instantly, signaling a new era where high fashion and street art could dance together. Even today, reissued Graffiti bags command astronomical resale prices.

But Jacobs did not stop there. In 2003, he tapped Japanese artist Takashi Murakami, whose “Superflat” philosophy merged manga joy with pop art audacity. The Multicolore Monogram exploded into 33 shades on a pristine white background. Cherry Blossoms giggled on bags; later, Cerises (cheeky cherries) winked on canvases once reserved for solemn brown and gold. Over 13 years, Murakami’s designs reportedly generated hundreds of millions of dollars for Vuitton, transforming the brand’s image from heritage-heavy to culturally unstoppable.

Then came Richard Prince in 2008, riffing off his Nurse Paintings with watercolor monograms. His “Aquarelle Monogram” splashed Vuitton in 17 hues, pushing the dialogue between fashion and art further. Suddenly, luxury wasn’t about quiet exclusivity—it was about bold statements.

If Murakami turned Louis Vuitton into pop art, Jeff Koons turned it into the Louvre on a handbag.

In 2017, Koons launched his “Masters” collection for Vuitton, reproducing works by Da Vinci, Van Gogh, Rubens, and Titian on Speedys, Neverfulls, and Keepalls. Gold lettering spelled out the artists’ names in unapologetic block type, while acrylic handles added a museum-ready gloss. “I wanted to erase the hierarchy between fine art and fashion,” Koons said. Critics rolled their eyes; customers lined up.

The collaboration expanded in 2018 with Monet and Gauguin, creating bags that were part accessory, part art history lesson. It was not just branding—it was branding masquerading as culture. Vuitton had turned a handbag into a portable gallery, priced for those who could afford to carry a Van Gogh under their arm.

If one artist embodies Vuitton’s genius for spectacle, it is Yayoi Kusama. First invited in 2012, her polka dots reappeared in 2023 in a collaboration so massive it spanned more than 400 products: bags, shoes, menswear, jewelry, even perfume bottles dotted as if by Kusama’s own brush.

The campaign was fronted by models who seemed to dissolve into dotted infinity. The Speedy bag sprouted hand-painted buttons; the Onthego tote shimmered with metallic dots. Vuitton was not just selling bags—it was selling Kusama’s philosophy of infinity, repetition, and wonder.

The collaboration confirmed Vuitton’s formula: choose artists who already command cult devotion, then amplify their universe through luxury craftsmanship. The result? Customers were not buying leather—they were buying belonging to an artistic legacy.

By 2024, Vuitton’s gaze had shifted eastward. The Pre-Fall collection introduced Sun Yitian, the Chinese artist known for her hyperreal paintings of toys and animals. Suddenly, pink rabbits, cheeky leopards, and glossy ducks leapt across Alma and OnTheGo bags.

This was not whimsy for whimsy’s sake. Vuitton was courting Asia’s booming luxury market by spotlighting a contemporary Chinese voice. The Animogram canvas fused youthful energy with global luxury, while limited-edition perfumes adorned with animal charms turned shopping into collecting. It was Vuitton speaking in the visual language of a new generation.

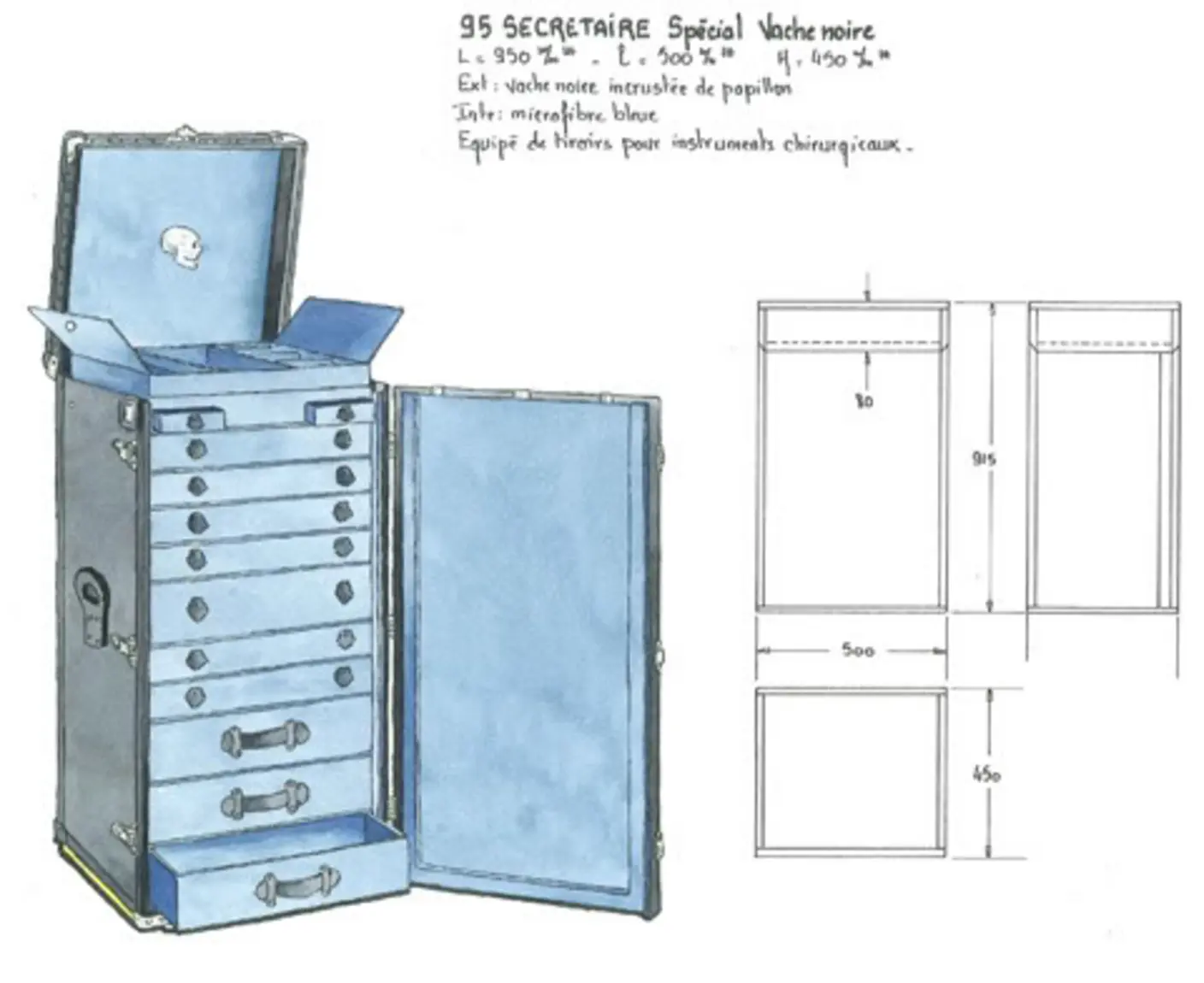

For Louis Vuitton, art is not confined to accessories. In 2009, Damien Hirst created trunks lined in deep blue microfibre, designed to hold surgical instruments—a macabre, almost unsettling marriage of fashion and mortality. In 2013, James Turrell built Akhob, a permanent ganzfeld light installation in Vuitton’s Las Vegas store, where 900 LED lights erased all sense of depth.

And in 2014, Bernard Arnault unveiled the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, a Frank Gehry-designed museum of 12 glass sails floating in the Bois de Boulogne. Inside, works by Richter, Kelly, and Abramović positioned Vuitton not just as a brand, but as a cultural patron. By 2024, its “Icons of Modern Art” exhibition had drawn over 1.2 million visitors—a reminder that Vuitton’s commitment to art goes far beyond the sales floor.

The story comes full circle in 2025, with Murakami’s much-hyped return. Two decades after he first painted Vuitton into pop culture, he is back with a three-chapter collaboration celebrating blossoms, cherries, and his playful panda mascot.

Over 200 new pieces revive the Multicolore palette, while the March drop reimagines Cherry Blossoms on classic brown monogram. May brings cherries dancing across Speedys and sneakers alike. Zendaya fronts the campaign, a candy-toned ode to Y2K nostalgia reframed for Gen Z.

It is not repetition but reinvention: a joyful remix of the past, proving Vuitton’s genius lies not only in creating spectacles but in recycling them for new audiences.

Louis Vuitton’s collaborations are not random flirtations; they are strategy. Each artist lends cultural capital, each collection refreshes the brand, and each launch guarantees headlines. A new creative director may struggle to reinvent the house, but an artist collaboration offers instant rebranding.

This is why Vuitton spends millions on PR blitzes, interviews, and glossy campaigns: to position each partnership as cultural history in the making. When an artist leaves, Vuitton does not mourn—it pivots. As one Vogue critic once quipped, “Poodles eat poodles.” In fashion’s survival game, it is not sentiment but spectacle that matters.

And while other luxury houses dabble in art, none have embraced it as wholly. Vuitton has turned itself into both canvas and curator, gallery and gift shop. A Vuitton bag is no longer just a bag—it is a ticket to belonging in the art world’s coolest club.

In the end, Vuitton’s genius lies in its ability to weave art into its DNA. From Sprouse’s graffiti rebellion to Murakami’s kawaii blossoms, from Koons’ Mona Lisa to Kusama’s infinity dots, the maison has made collaboration its crown jewel.

The results are not only visual delights but also financial triumphs. The Multicolore Monogram alone is rumored to have added over $300 million to Vuitton’s coffers. Kusama’s 2023 collection sold out globally, proving that art-fueled fashion has no expiration date.

Luxury today is not about discretion—it is about cultural visibility. And in that arena, Louis Vuitton has no rival. It is not just selling handbags; it is selling the dream of carrying art itself.