Jimmy Choo’s name is one of the most recognisable in fashion. But while the brand has become a billion-dollar business, the man himself has returned to his roots-teaching, crafting, and preserving the art of shoemaking. His story is less about empire and more about endurance.

Jimmy Choo’s name is one of the most recognisable in fashion. But while the brand has become a billion-dollar business, the man himself has returned to his roots-teaching, crafting, and preserving the art of shoemaking. His story is less about empire and more about endurance.

September 25, 2025

Some careers are born of chance. For Jimmy Choo, it began with a spelling mistake. Born in 1948 into a shoemaking family in Penang, Malaysia, his surname was mistakenly registered as “Choo” instead of “Chow.” The slip of a pen made his name rhyme with “shoe” - a coincidence that became prophecy.

Raised in the scent of leather and glue, Choo learned his craft not from textbooks but from silent apprenticeship. His father, also a shoemaker, gave him no instructions at first: “He told me to sit and watch for one month,” Choo recalls. “How to design, how to cut, how to finish.” The lesson was patience, discipline, and humility - virtues that would define his life as much as his shoes.

In the 1980s, London was not yet the global fashion capital it would become. But for Choo, then in his twenties, it represented opportunity. Malaysia, once a British colony, prized London training as a ticket to international credibility.

At Cordwainers Technical College - today part of London College of Fashion - Choo honed both craft and commerce. Life in London was a test of grit. He worked as a cleaner and restaurant worker to pay tuition, often sleeping little, often hungry. What sustained him, he admits, was the steady encouragement - and occasional remittances - from his mother.

Graduating in 1983, he opened his first workshop in the East End, in a disused hospital building. Customers trickled in, drawn by his reputation for precision: the arch perfectly balanced, the heel angled for grace as much as glamour. Yet success remained uncertain until Vogue intervened.

In 1988, Vogue featured his shoes in an eight-page spread. The story has since acquired the aura of legend. Choo could not afford a PR team, nor even transport to deliver his shoes. The magazine, recognising raw talent, sent a car to collect them.

The act was small, but for Choo it was transformative. “They didn’t look down on me,” he remembers. “They sent the car. That kindness, I will never forget.” The feature launched him into the fashion world’s consciousness. Orders multiplied. Celebrities took notice.

Among those who noticed was Princess Diana. She became not only a loyal client but a symbol of Choo’s aesthetic: understated elegance, poised yet comfortable, regal but approachable. Diana commissioned him for state dinners, charity galas, and private occasions.

Her endorsement gave Choo what no marketing budget could buy: credibility at the highest level. Soon, stars such as Beyoncé, Jennifer Lopez, and Madonna sought his designs. And when Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw cried out, “I lost my Choo!” in the late 1990s, the shoemaker’s name achieved a kind of immortality in popular culture.

The next step was scale. In 1996, Vogue accessories editor Tamara Mellon approached Choo with a proposition: to transform his bespoke workshop into a global luxury label. With financial backing from her father, Mellon and Choo co-founded Jimmy Choo Ltd.

The brand’s growth was swift. Ready-to-wear shoes complemented the bespoke service, boutiques opened in London, New York, and Los Angeles, and the “Jimmy Choo woman” became a byword for confident modern femininity. By the late 1990s, the brand’s revenues had surpassed $15 million annually, rare for a shoe label at the time.

Yet Choo, the artisan, grew uneasy with the brand’s direction. He preferred slow craftsmanship to scaling production, bespoke commissions to global expansion. In 2001, he sold his 50% stake for £10 million.

In the decades since, Jimmy Choo the brand has grown far beyond Jimmy Choo the man. It was acquired by private equity groups, listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2014, and bought by Michael Kors Holdings (now Capri Holdings) in 2017 for £896 million.

Today, the brand operates more than 200 stores worldwide. Capri Holdings reported Jimmy Choo revenues of $613 million in fiscal 2023, with handbags and accessories now accounting for a growing share of sales. In August 2023, Capri itself was acquired by Tapestry Inc., the American group that owns Coach and Kate Spade, in an $8.5 billion deal - further distancing the brand from its founder’s workshop origins.

And yet, in public imagination, the shoemaker and the brand remain intertwined. Customers often assume Jimmy Choo still designs the stilettos on Bond Street or Fifth Avenue, unaware that creative direction has long since passed to others.

Freed from corporate obligations, Jimmy Choo returned to his first love: couture shoemaking. In 2006, he launched Jimmy Choo Couture, a small bespoke line that served private clients with the same meticulous attention he once gave Princess Diana.

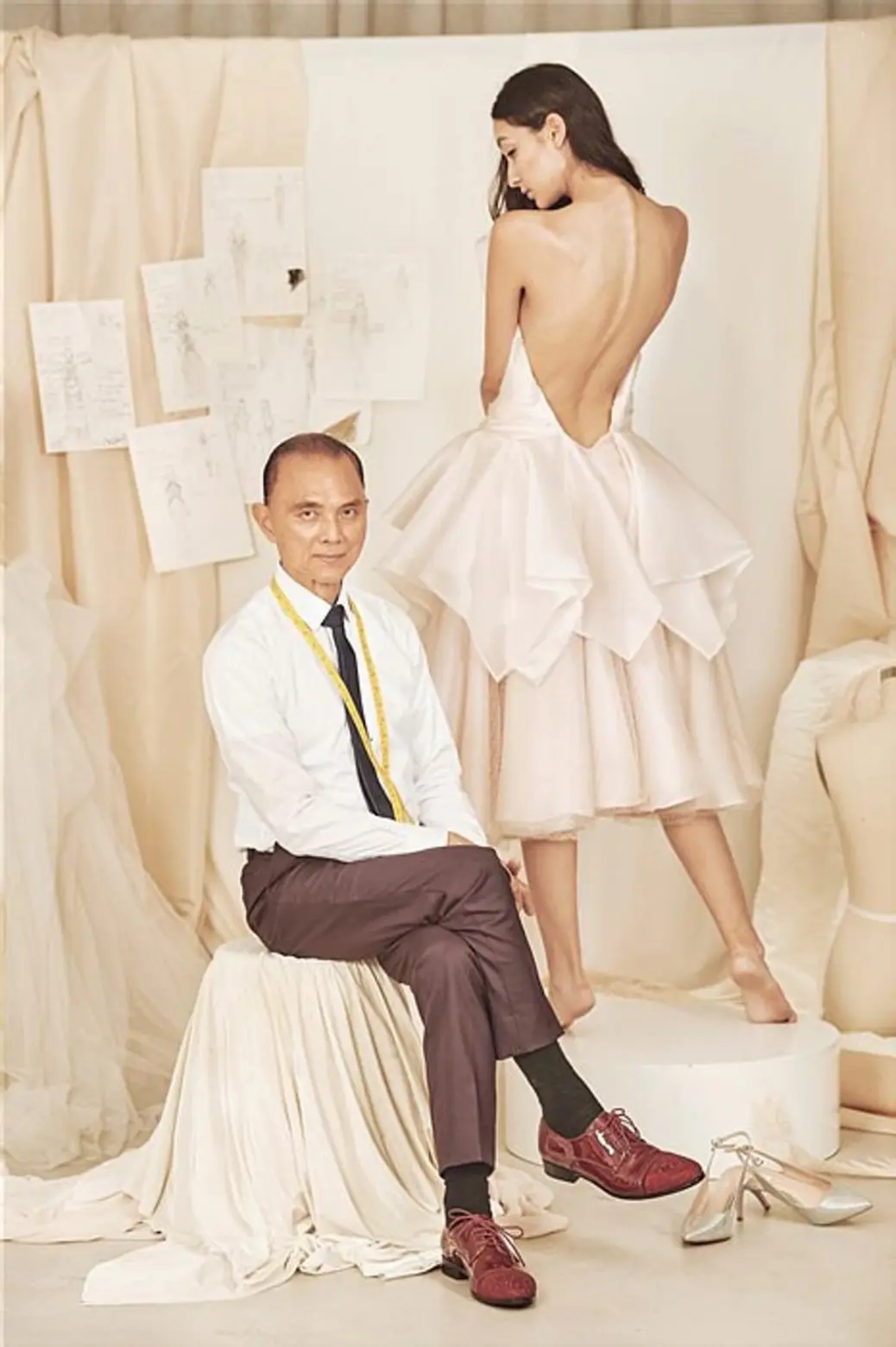

He also became creative director of The Atelier, a Malaysian luxury bridal and eveningwear brand, marrying his shoemaking sensibilities with couture dressmaking.

But perhaps his most enduring contribution is education. In 2021, he founded the Jimmy Choo Academy (JCA) in London, designed as both school and incubator. Its curriculum balances design with entrepreneurship, teaching students how to navigate the realities of a cutthroat industry.

“I select only 15 or 16 designs from hundreds of student ideas,” Choo says. “But more important than design is knowledge - that someone has taught them, guided them, cared for them. If knowledge is not passed down, slowly the skill will disappear.”

Choo’s legacy lies not only in workshops or runways but in culture. His designs have been displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, celebrated alongside Manolo Blahnik and Christian Louboutin. The Abel Pump, the Romy Heel, the Lance Sandal - all have become part of fashion’s lexicon.

More than accessories, his shoes became symbols. The Romy Heel, sleek and versatile, is now one of the brand’s best-sellers, often retailing at £495 - proof that the appetite for timeless design persists even in an age of fast fashion.

Yet, despite the glamour, Choo himself remains soft-spoken, almost self-effacing. Awarded the Malaysian title of “Datuk” for his global influence, he continues to attribute his success not to brilliance but to kindness - from his mother’s sacrifices, from Vogue’s generosity, from Princess Diana’s faith.

“I never succeeded on my own,” he insists. “I was lucky. Right timing, right occasion. People helped me, and I try to help others.”

Jimmy Choo’s life presents a paradox. His name adorns luxury stores from Dubai to Tokyo, yet he no longer designs for the brand. His career arc - from workshop to global stage, then back to workshop - resists the usual narrative of relentless expansion.

Instead, it affirms a quieter truth: that legacy is not always measured in billions, but in skills passed down, in students taught, in the shoemaker’s art preserved.

In an era when fashion often feels disposable, Jimmy Choo the man remains committed to permanence: one stitch, one sole, one lesson at a time.