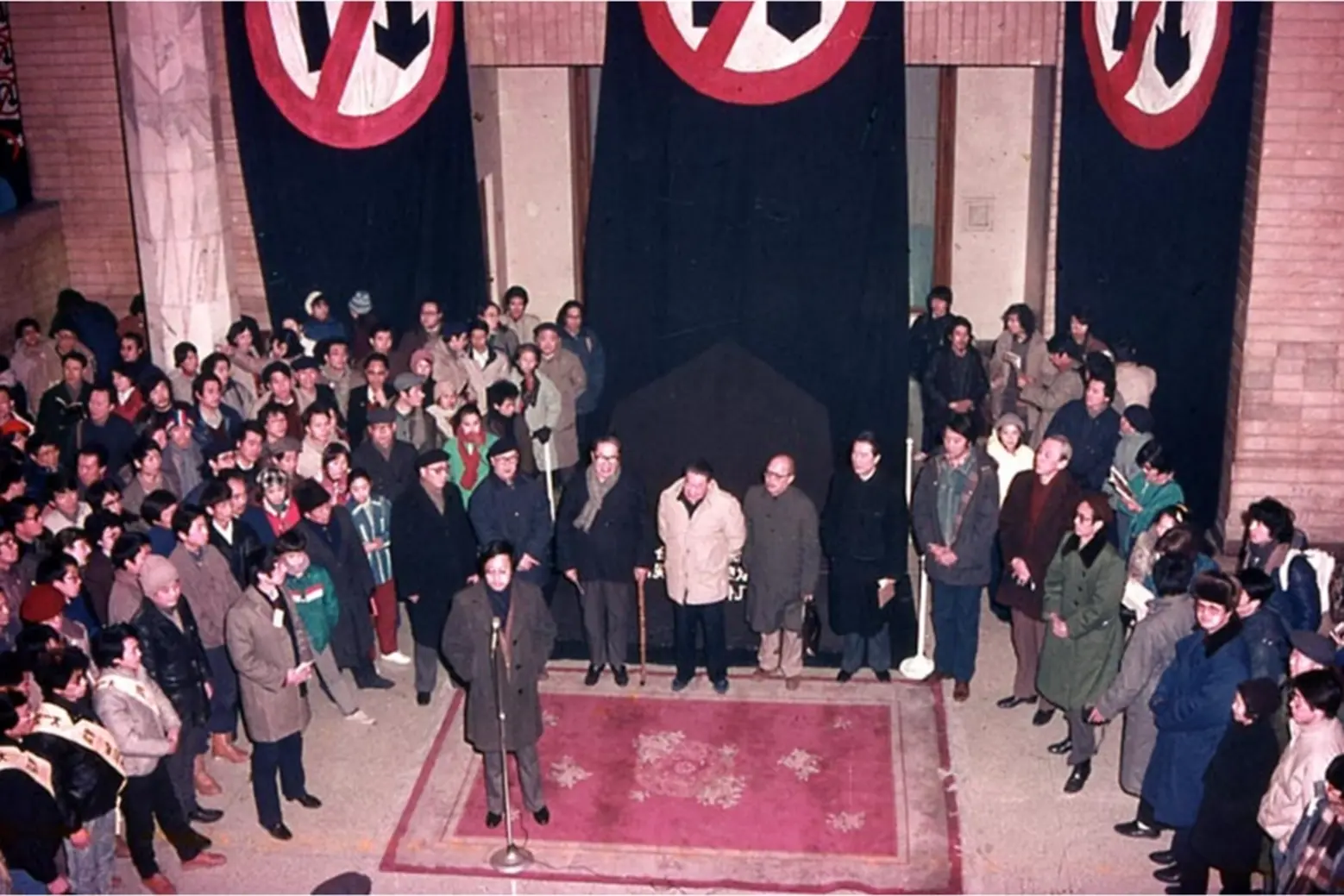

On February 5, 1989, Beijing witnessed a rupture in its cultural timeline at the National Art Museum of China.

On February 5, 1989, Beijing witnessed a rupture in its cultural timeline at the National Art Museum of China.

February 5, 2026

On February 5, 1989, Beijing witnessed a rupture in its cultural timeline at the National Art Museum of China.

The China/Avant-Garde Exhibition opened to the public, bringing together more than 186 artists and roughly 300 works in what remains the most consequential exhibition in the history of contemporary Chinese art.

Emerging from the intellectual aftershocks of the post-1985 New Wave, the exhibition functioned less as a survey than as a collective declaration. Painting, installation, performance, conceptual gestures, and acts of provocation crowded the museum halls, collapsing the distance between artwork and life. The curatorial vision, led by Gao Minglu alongside Li Xianting and Peng De, rejected aesthetic polish in favor of urgency. This was art that insisted on presence, friction, and risk.

That risk materialized almost immediately. The exhibition was forced to close just two hours after its opening, when artist Xiao Lu fired a gun at her own work, Dialogue. Four months later, following the Tiananmen Square massacre, these shots were retrospectively described by the media as “the first shots of Tiananmen.” In parallel, works such as Wu Shanzhuan’s market-style performance Big Business, which involved selling frozen shrimp inside the museum, dismantled any remaining boundary between institutional space and everyday economy.

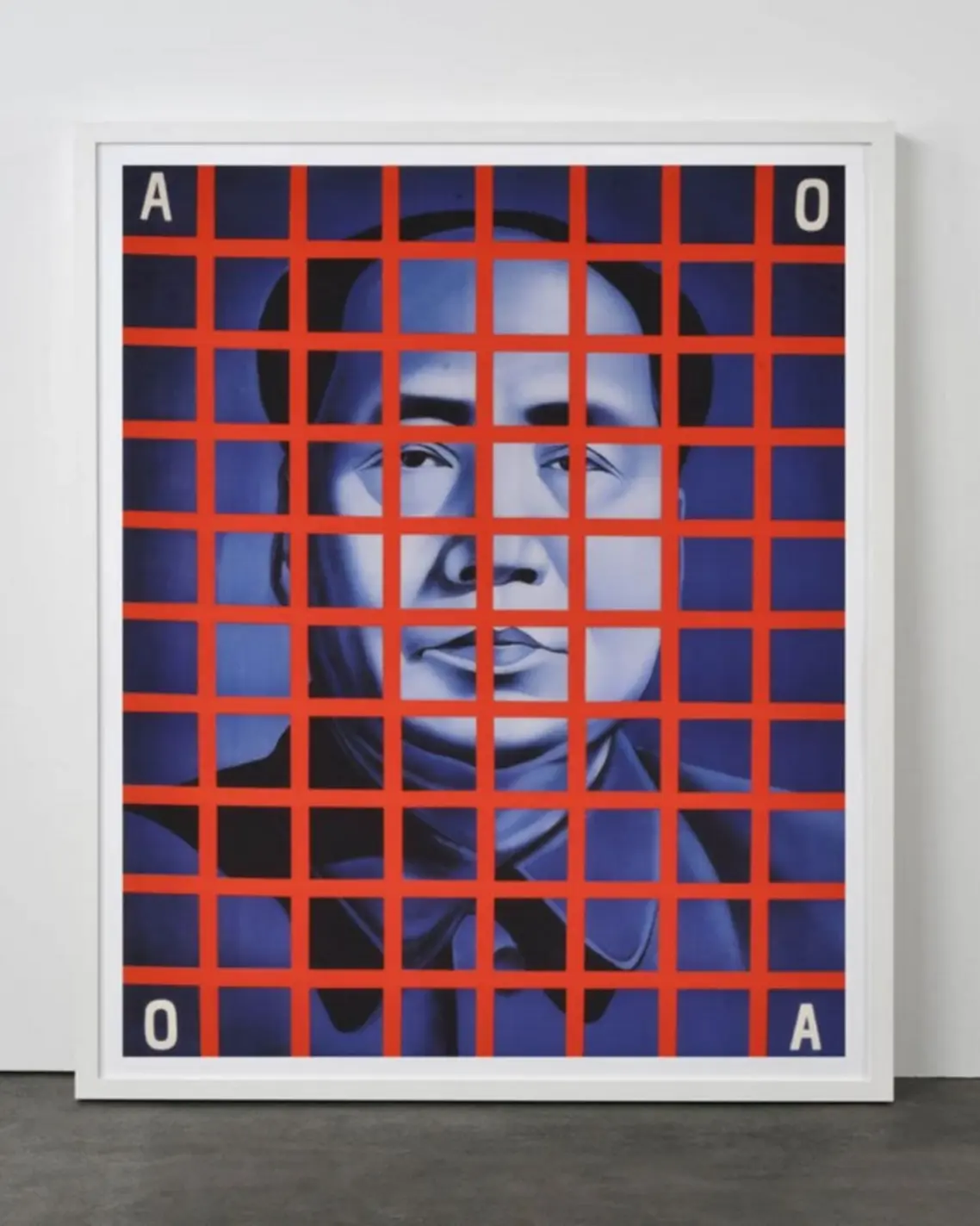

Visually, few images proved as enduring as Wang Guangyi’s Mao Zedong: Red Grid No.1. Referencing Cultural Revolution propaganda techniques, Wang Guangyi transformed ideological repetition into a cool, analytical language that would later define Political Pop. Elsewhere, figures like Zhang Peili explored video and conceptual systems that challenged narrative, authorship, and control.

Artists later recalled the exhibition less as a display than as a lived event. Zhang Peili famously compared it to a farmers’ market: chaotic, loud, collective, where anyone might suddenly become the protagonist. That atmosphere, raw and unstable, was precisely the point.

In the exhibition’s aftermath, many participating artists disappeared from public view, while others would go on to define China’s global contemporary art presence in the 1990s and beyond. Yet the exhibition’s true legacy lies in its courage. China/Avant-Garde did not seek permission, clarity, or consensus. It marked the moment when experimental Chinese art stepped fully into history, knowing the cost, and accepting it.