Frida, Mr. Turner, Pollock, Basquiat, and Big Eyes are five films that take the artist biopic and crank the volume past “life story” into something sharper: a public trial of pain, fame, authorship, and the brutal economics of being witnessed.

Frida, Mr. Turner, Pollock, Basquiat, and Big Eyes are five films that take the artist biopic and crank the volume past “life story” into something sharper: a public trial of pain, fame, authorship, and the brutal economics of being witnessed.

December 17, 2025

The door always opens the same way. A room that gives you nothing. Bad light. Hard air. A floor that remembers every spill, every collapse, every midnight decision. Silence, thick as varnish, daring you to make something worth the noise. Then the artist steps in and the air changes, because creation never arrives politely.

That is the real subject of these films. The messy physics of making. The bruise beneath the glamour. The hunger beneath the applause. The hand reaching for the signature, and the world reaching faster, eager to claim the credit, eager to sell the story, eager to turn a person into a product with a clean label.

Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002) arrives like a parade through a wound. It frames Frida Kahlo as a woman who refuses to live quietly, because her body will not let her, and her mind will not accept it. The film’s great trick is that it keeps folding life into art until you cannot separate them. The party scenes feel like murals. The hospital scenes feel like prayers. The love scenes feel like heat with teeth.

Kahlo explained her obsession with her own image with a line that reads like an artistic manifesto and a survival plan: “I paint self portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” Her paintings are not decoration in this story. They are events. When you think of The Two Fridas (1939), you feel the film’s doubleness echoing back: the public Frida, the private Frida, the split between identity and desire, stitched together by a pulsing line.

When you think of Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940), you feel how Kahlo makes symbolism behave like anatomy, beauty behaving like defiance. And when you land on Self Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), you catch quieter violence: reinvention as self surgery, a woman cutting away the version of herself the world expected to own.

Taymor’s film does something vital: it refuses to make Kahlo tidy. It gives her glamour and mess, tenderness and teeth. It treats her life the way her paintings treat her body: with brutal intimacy.

Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner (2014) is the opposite kind of biopic spectacle. It lowers the volume until you can hear the scrape of a brush, the grunt of a man thinking, the hush of a coastline about to turn mythic. Leigh focuses on the last twenty five years of J. M. W. Turner’s life, and Timothy Spall plays him like a storm contained in a human suit: heavy, awkward, fiercely private, and unignorable.

This film is a masterclass in what Turner believed painting could do: make atmosphere into meaning. Turner once answered a complaint with a line that could be engraved on the door of modern art: “You should tell him that indistinctness is my forte.” That sentence explains the film’s visual philosophy too. Edges blur. Weather takes over. Details dissolve into sensation.

Turner’s paintings become the film’s grammar. Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) sits at the center like a prophecy, a train tearing through a world that still thinks nature is the only sublime power worth fearing. You feel Turner painting modernity as a force that cannot be reasoned with, only witnessed. And when the film circles the cultural weight of works like The Fighting Temeraire (1839), you sense Turner as a historian of endings, a painter who could make national pride look like a funeral lit from within.

Ed Harris’s Pollock (2000) does something rare: it refuses to treat the artist as a lone hero. It tells the story as a two person collision, with Lee Krasner as more than a supportive spouse and more than a footnote. The film centers Jackson Pollock’s rise and his alcoholism, yet it keeps returning to the marriage as the real battlefield: affection, ambition, damage, devotion, all tangled together.

Pollock’s own words land like a thesis for the entire film: “Painting is self discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.” Pollock takes that idea literally and shows self discovery as a brutal process. Art becomes the place where Pollock can be free, and also the place where he exposes how trapped he feels everywhere else.

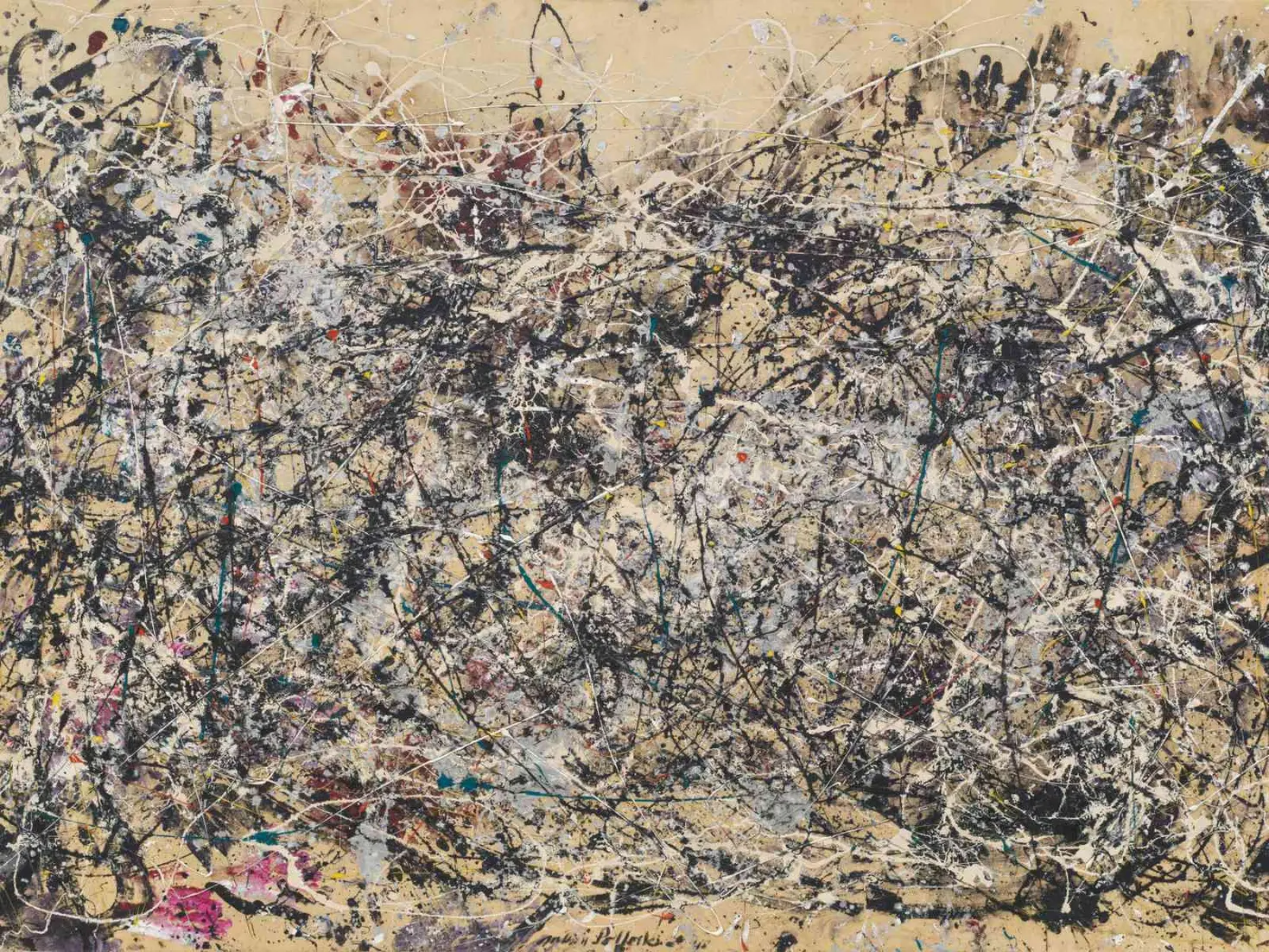

The movie makes you look at the paintings with fresh dread and awe. When you think of a drip work like Number 1A, 1948, you feel the scale as physical, a body moving around a canvas like a ritual. The film turns that movement into choreography, and you begin to understand why those surfaces feel like records of weather and nerves at once.

Then Krasner steps forward, claiming the frame back. Her quote cuts through the mythology of the tortured male genius with perfect clarity: “I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent…” The film’s power comes from letting that truth sit beside Pollock’s legend. It asks who gets remembered, who gets reduced, and how history edits women into supporting roles even when they are making the work, the life, the survival.

Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996) feels like a downtown fever dream captured before it evaporated. It is a film about Jean Michel Basquiat, yes, yet it is also about New York as a machine that consumes youth and sells the glow back as myth.

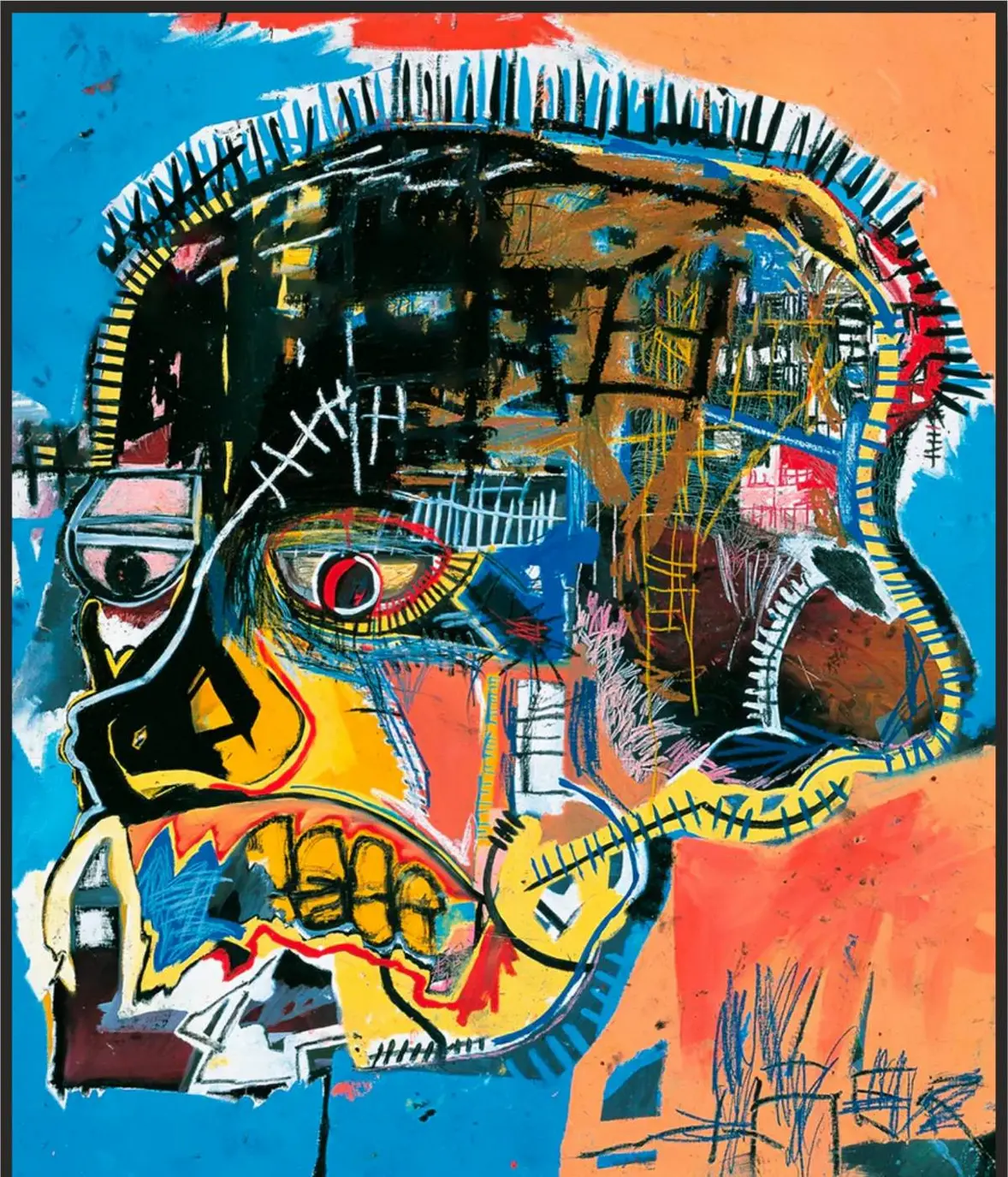

His most famous images also carry the film’s pulse: the head that looks like a skull yet reads like a portrait of mind under pressure, in Untitled (Skull) (1981). The film keeps returning to the same tension you see in that work: vitality and doom, brilliance and exhaustion, humor and grief.

A quote often associated with Basquiat describes his process with disarming directness: “I don’t think about art when I’m working. I try to think about life.” Watch the film through that lens and his whole rise becomes tragic in a very specific way. The world wanted his life as spectacle, yet his work wanted life as raw material, unfiltered and alive.

Then comes Big Eyes (2014), Tim Burton’s pop colored courtroom fable about Margaret Keane, whose wide eyed children became a mid century sensation while her husband Walter Keane claimed authorship. This film flips the usual artist biopic arc. The question is not “can she make it.” The question is “can she get her name back.”

There is an extra layer of symmetry here, because Burton has his own lifelong fascination with oversized, expressive eyes, from his earliest drawings through the visual DNA of his films. So when Keane explains her fixation with a line that sounds simple until you feel its weight, “Eyes are windows of the soul,” it lands as shared language. Burton treats it as both aesthetic and emotional logic. The eyes become a vocabulary for fear, longing, and control. The paintings read sweet at first glance, yet the story underneath them is about silence pressed into a woman’s mouth.

Then the film reaches its signature moment, stranger than fiction because it is documented: the judge ordered both Margaret and Walter to paint in court. Walter declined, citing a sore shoulder, while Margaret completed a painting in fifty three minutes. In a genre that loves grand speeches, Big Eyes delivers its climax through action: art as proof, authorship as a physical fact.

By the time the fifth film ends, the gallery has done its work. You came for biography and left with something sharper: art is not only talent, it is power. Who gets credited. Who gets consumed. Who gets remembered. Watch them together and the myth collapses into mechanics: gatekeepers, appetites, stolen signatures, stories sold cleaner than the lives that made them. Yet the films leave one fierce reassurance behind. The masterpiece is the act of making anyway. In bad light. In hard silence. With the world reaching for the work, and the artist reaching back, insisting, again and again, on their own name.