Kunstsilo in Kristiansand opened its doors in 2024 inside a converted 1930s grain silo, and it has moved fast from architectural headline to serious destination. From February 5 to May 10, 2026, the museum stages a statement exhibition, “Edvard Munch – Portraits,” an adapted, expanded version of the National Portrait Gallery’s acclaimed 2025 London presentation.

Kunstsilo in Kristiansand opened its doors in 2024 inside a converted 1930s grain silo, and it has moved fast from architectural headline to serious destination. From February 5 to May 10, 2026, the museum stages a statement exhibition, “Edvard Munch – Portraits,” an adapted, expanded version of the National Portrait Gallery’s acclaimed 2025 London presentation.

February 5, 2026

This exhibition matters for another reason: it travels with pedigree. Kunstsilo presents an adapted, expanded edition of the exhibition first shown at London’s National Portrait Gallery in spring 2025, a landmark survey that reframed Edvard Munch’s portrait practice as essential rather than side chapter.

The curatorial idea lands with clarity. Instead of rehearsing the familiar lone genius storyline, the exhibition places Munch inside his web of family, friends, lovers, writers, artists, patrons, and collectors. Each portrait reads like a pin on a map: who he loved, who he admired, who commissioned him, who challenged him, who helped shape his public identity. Kunstsilo frames the show as a “rare entry point” into lesser seen dimensions of his practice, with relationships as the connective tissue.

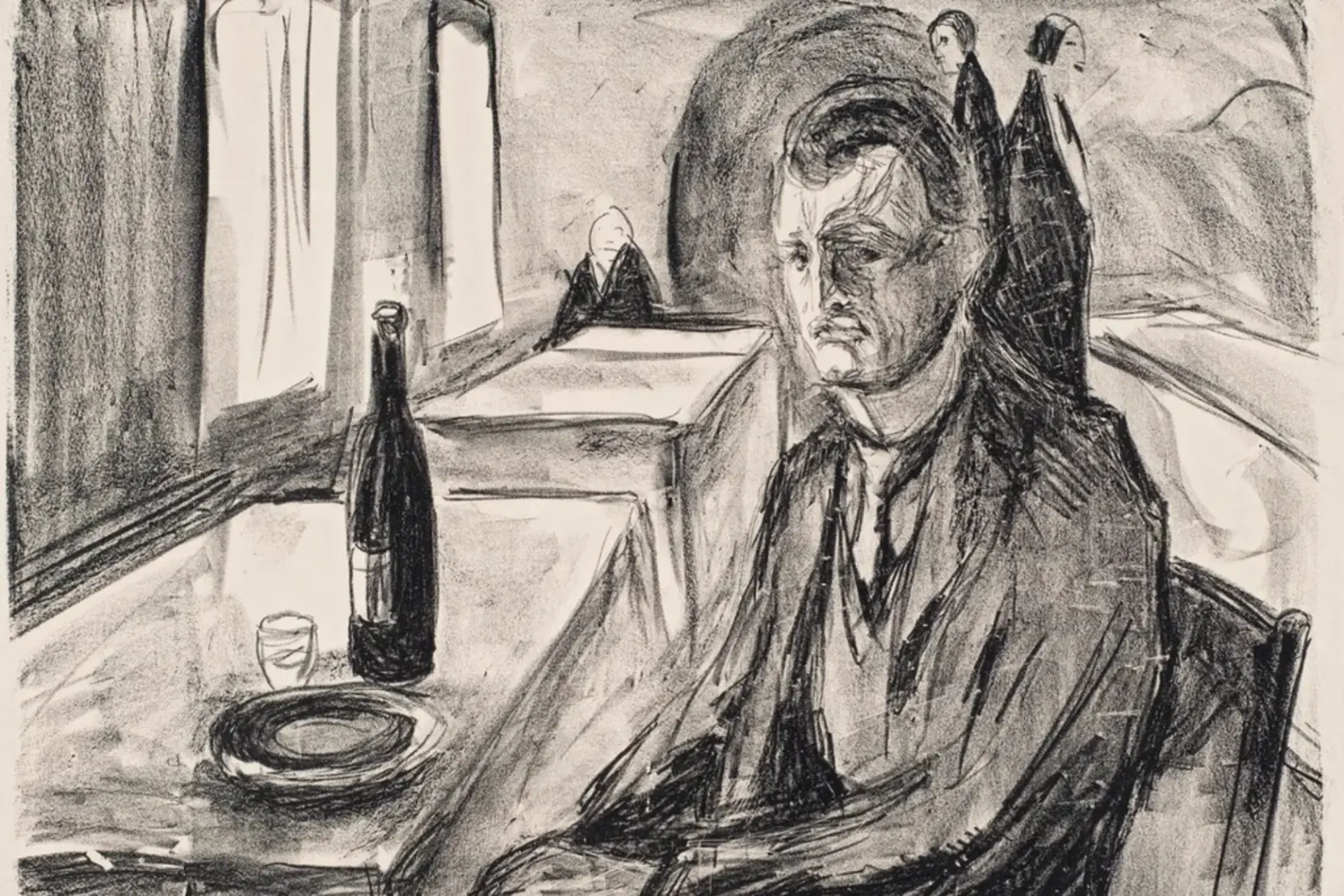

That social lens also sharpens psychology. Munch approaches portraiture with energetic brushwork and bold colour, shifting format, framing, and background depending on proximity and power dynamics. In the London edition, critics and writers kept returning to the same sensation: these faces carry atmosphere, tension, and an emotional temperature that feels almost confrontational.

Munch had a line that captures his approach with mischievous precision: “When I paint a person, his enemies always find the portrait a good likeness.” It is funny, sharp, and revealing. He understood portraiture as exposure: a likeness of how someone reads in a room, in society, in conflict, in desire.

Kunstsilo’s version includes additions beyond the London presentation and highlights works rooted in the museum’s own history. A key anchor is the Portrait of Klemens Stang (1885–86), described by Kunstsilo as the only Munch painting in the Christianssands Picture Gallery collection, now part of its holdings. The Edvard Munch – Portraits exhibition also foregrounds graphic portraiture from the collection, including Self Portrait with Wine (1930), a late-life image that turns self depiction into a distilled mood.

And then there is the building itself: a former grain silo converted into a contemporary museum, a piece of architecture that makes the visit feel like an event before you even enter the galleries.

For travelers who chase museum exhibitions with a strong point of view, this is the kind of show that offers both mythmaking and correction: Munch as a social artist, a commissioned portraitist, a reader of faces, a builder of reputations. Put simply, the Edvard Munch – Portraits belongs on any shortlist of museum exhibitions worth travelling for.