Each December 2, the art world pauses to honor George Seurat, the quiet French visionary whose meticulous eye and scientific curiosity transformed the course of modern painting.

Each December 2, the art world pauses to honor George Seurat, the quiet French visionary whose meticulous eye and scientific curiosity transformed the course of modern painting.

December 8, 2025

Each December 2, the art world pauses to honor George Seurat, the quiet French visionary whose meticulous eye and scientific curiosity transformed the course of modern painting.

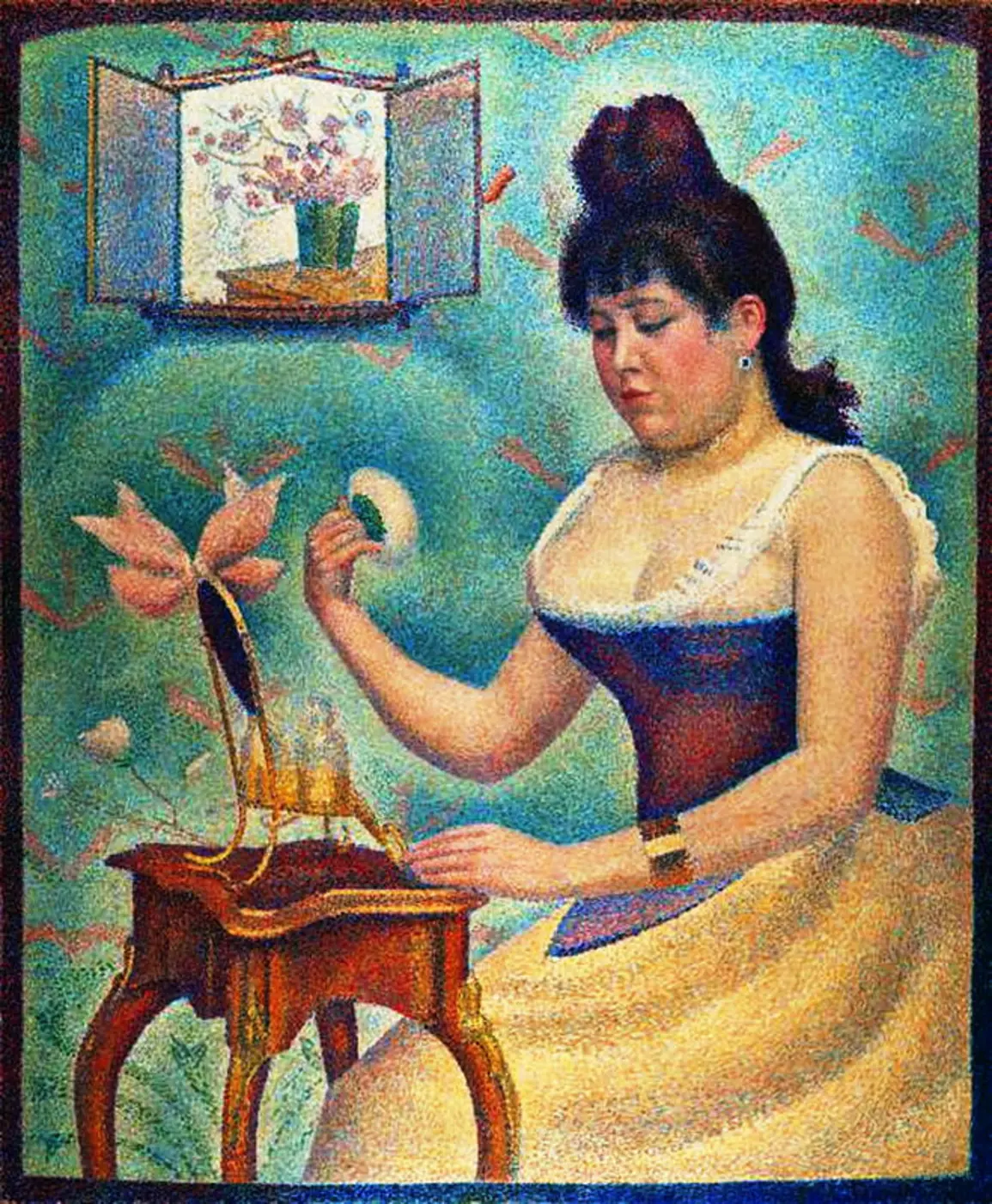

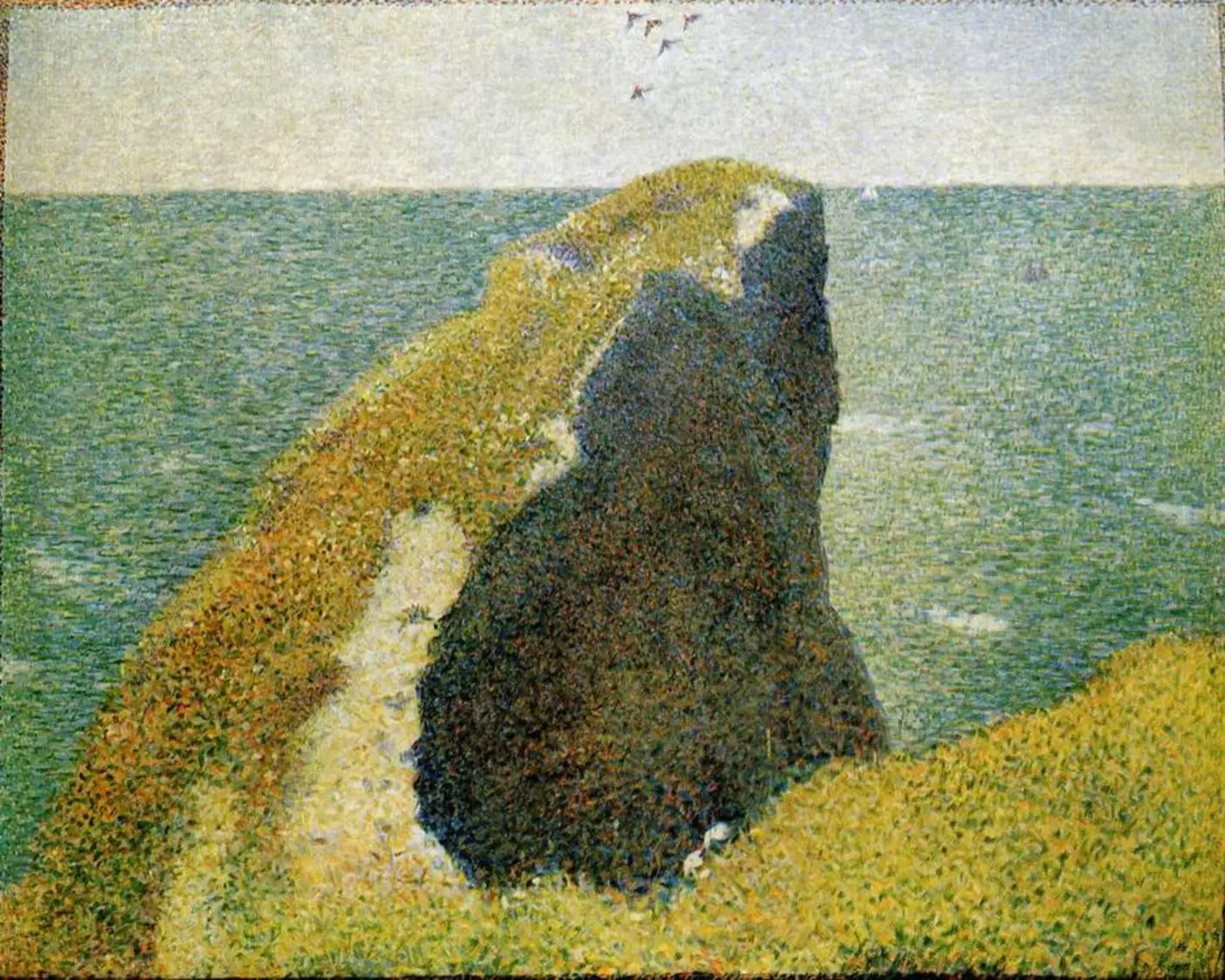

Born in 1859, Seurat was not a flamboyant figure in the cafés of Paris nor a provocateur of manifestos; instead, he was a patient architect of light, devoting himself to a radical idea: that color, when broken into tiny points, could shimmer with greater intensity than any brushstroke of blended pigment.

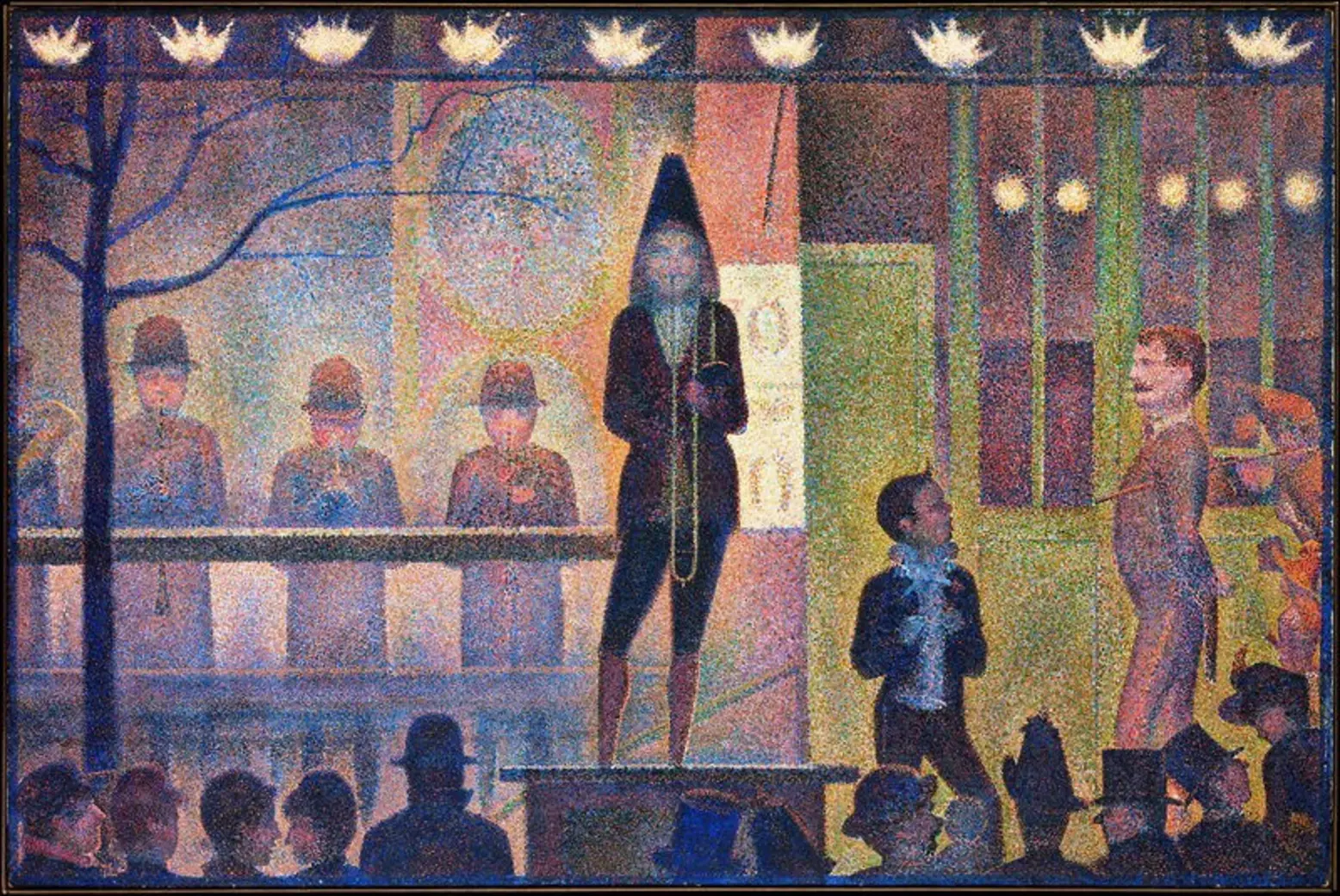

Seurat’s birthday is a celebration of a mindset. At a time when Impressionism thrived on spontaneity, he moved in the opposite direction, building his works with the discipline of a mathematician and the soul of a poet. Seurat studied color theory obsessively, filling notebooks with formulas and diagrams before putting a single dot on canvas. His masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), is the ultimate expression of this vision: a scene of everyday leisure transformed into a mosaic of light, where thousands of dots coalesce into an atmosphere at once serene, structured, and dreamlike. Seurat obsessed over this masterpiece for years, secretly returned to the canvas multiple times to refine its light effects.

The opening of this monumental canvas to the public marked a decisive moment in art history. Critics were baffled, admirers were mesmerized, and younger artists, including Signac, Pissarro, and later the Fauves, found in Seurat a model for bridging intuition with science. Today, the painting remains one of the world’s most recognizable images, not only for its technical innovation but for its enduring emotional resonance. It captures a Paris, both ordinary and mythical, suspended in an eternal afternoon.

What makes Seurat’s legacy especially powerful is its longevity. His method, later called Pointillism or Divisionism, laid the groundwork for optical theory in art, influencing movements from Neo-Impressionism and Fauvism to contemporary digital pixel-based aesthetics. In an age obsessed with screens, grids, and pixels, Seurat feels startlingly modern, a 19th-century artist whose sensitivity aligned with the visual language of the 21st.

On his birthday, we remember a man who worked in silence yet sparked a revolution. George Seurat expanded not only what painting could look like, but how it could think. His art remains a testament to slow creation, patient vision, and the profound beauty that emerges when science and imagination meet.