In 1965, Yves Saint Laurent took modern art off the museum wall and onto the runway. With six cocktail dresses — now fetching up to $47,000 at auction — he turned a painting into a manifesto for the Swinging Sixties.

In 1965, Yves Saint Laurent took modern art off the museum wall and onto the runway. With six cocktail dresses — now fetching up to $47,000 at auction — he turned a painting into a manifesto for the Swinging Sixties.

September 29, 2025

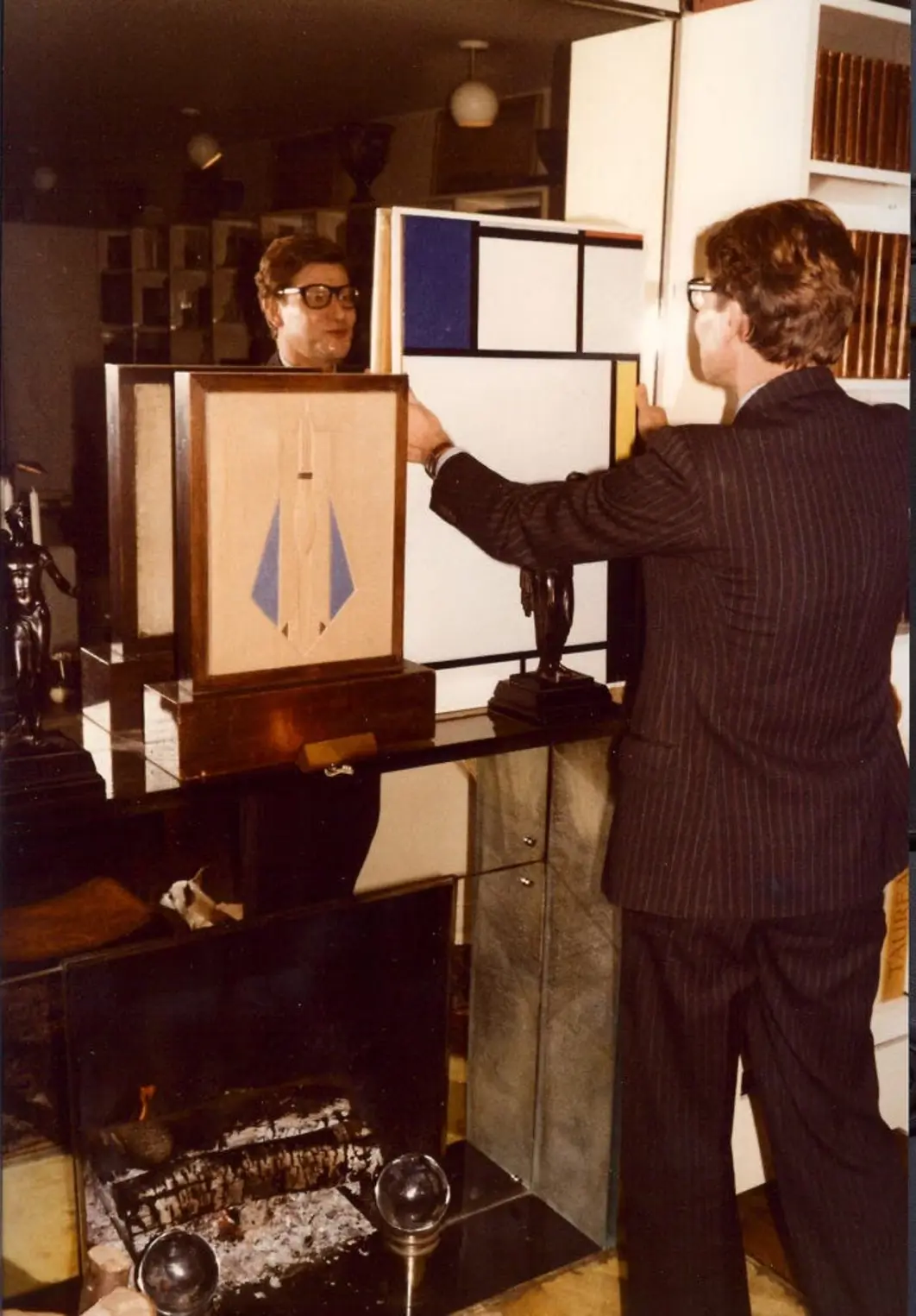

When De Stijl shook Europe with its stark geometry, Yves Saint Laurent responded not with paint but with needle and thread. His 1965 Mondrian Collection was a cultural thunderclap: six A-line cocktail dresses that looked as if they had walked straight out of a gallery. Canvases became clothing, and gallery walls gave way to couture seams.

The De Stijl movement, born in the Netherlands after the First World War, was a purist manifesto: a world of straight lines, primary colors, and geometric clarity. Piet Mondrian — prophet of Neoplasticism — rejected the chaos of nature’s hues for a transcendent balance of red, blue, yellow, black, and white.

By 1965, Paris was primed for a similar rupture. Courrèges was shooting fashion into the Space Age, and a restless 29-year-old Yves Saint Laurent was itching to break free of old-world couture stiffness. “I was stuck in a traditional form of elegance, and Courrèges took me out of it,” he confessed.

That Christmas, his mother gave him a book of Mondrian’s work. Inspiration struck with the force of a Roy Lichtenstein “WHAM!” — and within months, Saint Laurent sketched the pieces that would define his decade.

The Mondrian Collection — six cocktail dresses of wool jersey and silk crêpe — debuted for Autumn/Winter 1965. At first glance, they seemed deceptively simple: cream-colored canvases sliced by black bars and punctuated by squares of color. But these were no printed panels. Each block was meticulously inlaid into the fabric, seams hidden with couture precision, so perfectly the garments appeared painted in a single stroke. This level of craftsmanship reshaped how couture workshops approached cutting, stitching, and structure.

Paired with Roger Vivier’s square-buckled “Pilgrim” pumps, geometric jewelry, and hats echoing Mondrian’s palette, the look became a manifesto in motion — wearable art with the rigor of haute couture.

The effect was electric. Diana Vreeland raved in The New York Times that it was “the best collection,” while Women’s Wear Daily crowned Yves “the king of Paris.” Vogue immortalized the look on its September 1965 cover, sending the dresses into fashion legend.

Saint Laurent’s genius was not only aesthetic but cultural: he blurred the lines between elite art and ready-to-wear. Licensed patterns for the Mondrian dress appeared in Vogue, allowing women to make their own versions at home, and fast copies flooded American department stores. The grid became an instant Sixties symbol, as ubiquitous as the miniskirt.

Even beyond fashion, Mondrian mania spread. Models in Mondrian shifts were used to promote the 1966 Oldsmobile Toronado in Detroit, proving that this wasn’t just a couture statement but a full-blown pop-cultural phenomenon.

Today, these dresses are among the most collectible pieces of twentieth-century couture. In 2011, one of the six originals sold at Christie’s London for £30,000 (about $47,000) — proof that their value, both cultural and financial, has only grown. Museums from FIT in New York to the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris continue to exhibit them, cementing their status as wearable works of art.

Saint Laurent revisited the motif multiple times: haute couture in 1980, Rive Gauche in 1997, and again in his emotional farewell show in 2002. Designers followed suit: Francesco Maria Bandini staged a Mondrian-inspired collection in 1991, and Christian Louboutin created the cheeky “Mondriana” pump in 2007.

Biographer Laurence Benaïm calls the Mondrian dress “the first haute couture dress to be an object of consumption” — a prescient observation about the growing power of fashion as cultural currency.

Saint Laurent’s Mondrian Collection was not mere homage. It was a cultural bombshell that fused art, couture, and commerce — and detonated with a pop-colored bang. With a few hidden seams and a painter’s palette, Yves turned women into walking exhibitions of modernism, proving that fashion could be as radical, as intellectual, and as transformative as any avant-garde painting.