Step inside one of the world’s most enchanting libraries: the Vatican, Trinity College Dublin’s Long Room, Austria’s Admont Abbey, and Rio’s Real Gabinete Português. Discover where books become treasures, reading rooms feel like cathedrals, and history pulses on every page. A journey for anyone who believes in the magic of a preserved library of words.

Step inside one of the world’s most enchanting libraries: the Vatican, Trinity College Dublin’s Long Room, Austria’s Admont Abbey, and Rio’s Real Gabinete Português. Discover where books become treasures, reading rooms feel like cathedrals, and history pulses on every page. A journey for anyone who believes in the magic of a preserved library of words.

December 17, 2025

This story takes place in four libraries that feel like fairy tales you can enter - Rome’s guarded vaults, Dublin’s endless timber hall, Austria’s luminous monastery dream, and Rio’s jewel-box of Portuguese wisdom, where astonishing collection numbers and headline-making auction prices reveal the truth: a book can be treasure, and a reading room can be pure enchantment.

A corridor narrows your world into one straight line. The air cools, as if it is measuring your intentions. Your pace softens. You start walking the way people walk into cathedrals: slowly, quietly, almost reverently.

You find yourself reading the room before you read a single title. You learn which book is allowed to be touched and which book must only be admired with your hands held still.

Then the space opens, and the plot thickens.

On June 15, 1475, Pope Sixtus IV gave the Vatican Apostolic Library its formal beginning. Six centuries later, it still feels like a Renaissance workshop held to a sacred standard, where ink becomes legacy and preservation becomes devotion. Under Pope Sixtus V, a three storey wing was drawn cleanly across Bramante’s Cortile del Belvedere, and the courtyard itself began to speak in symbols, one side carrying the pulse of palace life, the other guarding the Library’s archival hush.

The shelves refuse a single identity. Scripture stands at the center, then the collection fans outward into canon law, philosophy, history, and science, before settling into the long classical backbone of Greek and Latin writers, with medieval copies of voices like Vergil and Terence still breathing through their margins. Altogether, it reads like a civilization placed gently in trust: about 80,000 manuscripts, around 1.6 million printed books, more than 8,600 incunabula, plus coins, medals, prints, and photographs.

And then the paradox sharpens the spell. On paper, such cultural treasures may sit at a symbolic one euro, yet their true gravity lives beyond price. Here, Codex Vaticanus, a fourth century Greek Bible manuscript, and the Vatican Virgil, made around 400 CE, rest in a realm where uniqueness becomes its own currency. Outside these walls, the market tells a rougher story in numbers, with the Codex Sassoon reaching about 38 million dollars in 2023 and Leonardo’s Codex Leicester selling for 30,802,500 dollars in 1994, yet inside, the Library keeps the greater equation: value measured in survival, in access, in time.

The Trinity’s own description gives the headline stat: nearly 65 metres in length, normally filled with around 200,000 of the Library’s oldest books.

The spell begins with the Book of Kells, a ninth century Gospel book where Latin scripture flowers into Celtic knotwork, spirals, and figures so delicate they seem to move when the light shifts. Its legend carries a medieval shock of theft and recovery, stolen in 1006 for its jeweled cover, returned months later without the gold yet miraculously saved as a book. Nearby, the Brian Boru Harp brings the room from manuscript to nation, a medieval instrument often dated to the fifteenth century whose silhouette became Ireland’s emblem. Then the story steps into modern fire and declaration with the 1916 Proclamation, read by Patrick Pearse outside the GPO on 24 April 1916, a surviving sheet treated like a relic of statehood and prized at auction in six figure sums.

Yet the quiet backbone of Trinity’s reputation lives beyond the celebrity objects. The Fagel Collection arrived like a tide in 1802, when the Napoleonic era pushed the powerful Dutch Fagel family into financial crisis and their working library faced dispersal. Trinity bought it intact at a London sale, supported by the Erasmus Smith Trust, keeping the collection whole. The scale still lands with a sense of thunder: about twenty thousand volumes carrying more than thirty thousand titles and around eleven thousand maps, shipped in one hundred and fifteen crates, expanding the library by roughly forty percent almost overnight.

And the Long Room keeps proving that age can be a living thing. Trinity’s Old Library redevelopment has required removing two hundred thousand books from the chamber so the building and its collections can endure. That single fact reads like a plot point: the hall temporarily emptied so its future can stay full.

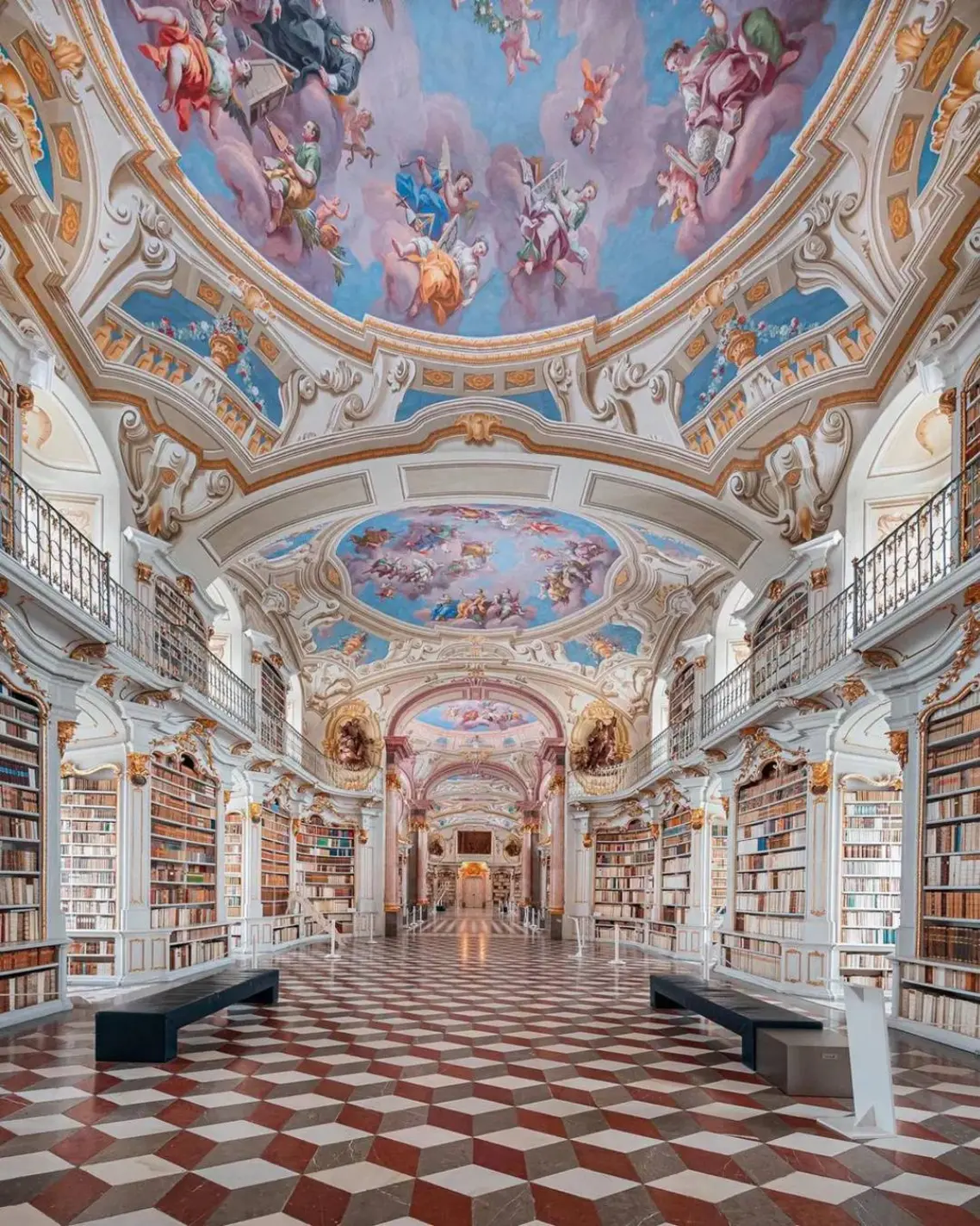

Admont Abbey Library reads like daylight given walls. Finished in 1776 to Josef Hueber’s design, the hall runs 70 metres in a calm tripartite rhythm, crowned by seven domes painted by Bartolomeo Altomonte in his eighties. Each cupola pulls your gaze through the stages of human knowledge toward a final, luminous center. Light streams through 48 windows, ricocheting across the library’s white and gold palette until scholarship feels radiant, almost theatrical.

Step deeper and the room begins its refined illusions. The marble mosaic floor, assembled from thousands of small pieces, shimmers into optical patterns as you move. Seamless shelves conceal secret doors disguised as book spines, opening to spiral staircases that make the upper galleries feel as if they hover within reach. At the heart of all this brightness stands Josef Stammel’s carved group of the Four Last Things, a dramatic moral anchor placed right in the glow.

Travelers love the nickname “Disney library,” and Beauty and the Beast comparisons follow naturally, with the origin story living in popular lore. The documented marvel sits in the collection itself: around 200,000 volumes, more than 1,400 manuscripts dating from the 8th century onward, and 530 incunabula. The abbey also carries the thrill of discovery, including the famous Abrogans fragment from the 8th century, alongside its own survival legend, after the 1865 fire devastated much of the monastery while the library endured.

In the heart of Rio de Janeiro, the Real Gabinete Português de Leitura rises as a Gothic revival dream made solid, a sanctuary where the Portuguese language feels almost consecrated. Founded in 1837 by immigrants searching for a cultural anchor, it became a bridge across the Atlantic, holding community memory together through books.

Its building performs its own kind of devotion. Designed in the Neo Manueline style that nods to Portugal’s Age of Discovery, the façade was carved from Lioz limestone in Lisbon workshops and shipped across the ocean. Stone figures like Vasco da Gama and Luís de Camões watch the entrance, as if the exterior itself is a prologue to the maritime history inside.

Step into the great hall and the city fades. Dark carved wooden shelves climb four stories toward a ceiling about twenty three metres high, turning the room into a vertical ocean of literature. Nearly 400,000 volumes line the walls in a rising mosaic of colour and thought. Above, wrought iron and stained glass filter the tropical light into a warm glow, making the space feel like a living manuscript.

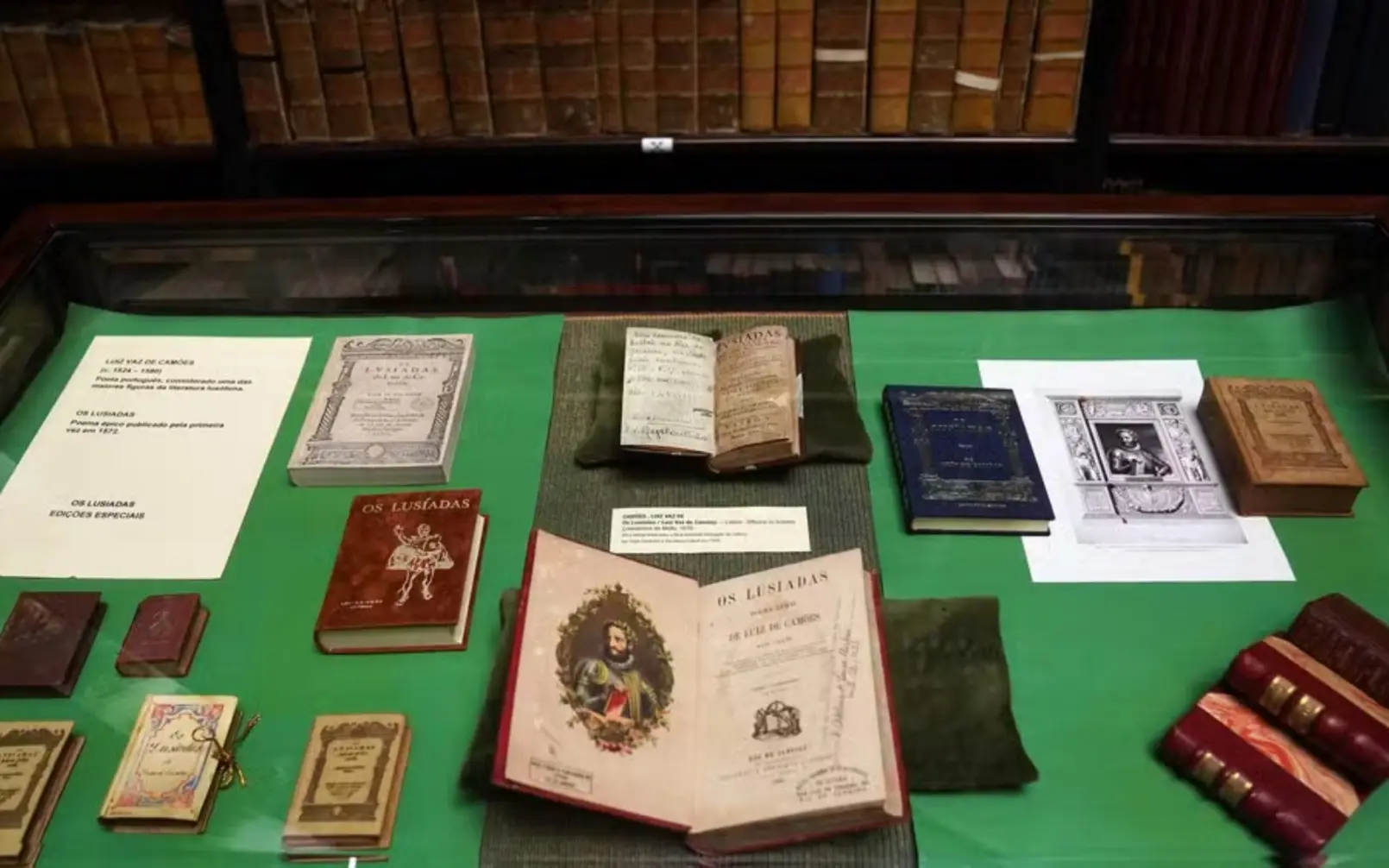

The collection holds true relics, including a rare 1572 first edition of Os Lusíadas by Camões. In 1906, King Carlos I granted it the Royal title, sealing its role as a cultural guardian. At the center stands the Altar da Pátria, a monument of silver, ivory, and black marble crafted in Porto, a tribute to navigators and dreamers who carried a language across the sea.

This remains a working institution, with a modern lifeline that keeps the shelves evolving. Since 1935, it has held Legal Deposit rights, receiving a copy of every book published in Portugal. That steady arrival of new pages helps sustain the largest collection of Portuguese literature outside Portugal, a place where heritage stays present, and the tide of time keeps meeting its match in ink.

In the end, every fairy tale returns to the same truth: treasure changes hands, yet wonder stays. Rome keeps its rarest pages like relics, Dublin lets a nation’s symbols breathe in timber light, Admont turns knowledge into sunrise, and Rio lifts language into a cathedral of carved stone and stained glass. Each room teaches a different kind of reverence, and each one leaves you with the same quiet aftertaste, the feeling that history still has a pulse.

Step back into the street and you carry the spell with you. A library is a promise made physical: that stories can outlive empires, that careful hands can outlast fire. And somewhere, behind glass, behind velvet ropes, behind a screen lit by digitized ink, the next reader arrives, breathes in, and turns the page.