In a fashion world long governed by unspoken rules, Nick Knight has always been the first to ask, “Why must it be this way?” and immediately follow with, “What if we break it?” From the raw, confrontational Skinhead portraits of his early career to the experimental projects on SHOWstudio, Knight has never merely “documented” fashion; he has reconstructed it.

In a fashion world long governed by unspoken rules, Nick Knight has always been the first to ask, “Why must it be this way?” and immediately follow with, “What if we break it?” From the raw, confrontational Skinhead portraits of his early career to the experimental projects on SHOWstudio, Knight has never merely “documented” fashion; he has reconstructed it.

November 20, 2025

In a fashion world long governed by unspoken rules, Nick Knight has always been the first to ask, “Why must it be this way?” and immediately follow with, “What if we break it?” From the raw, confrontational Skinhead portraits of his early career to the experimental projects on SHOWstudio, Knight has never merely “documented” fashion; he has reconstructed it.

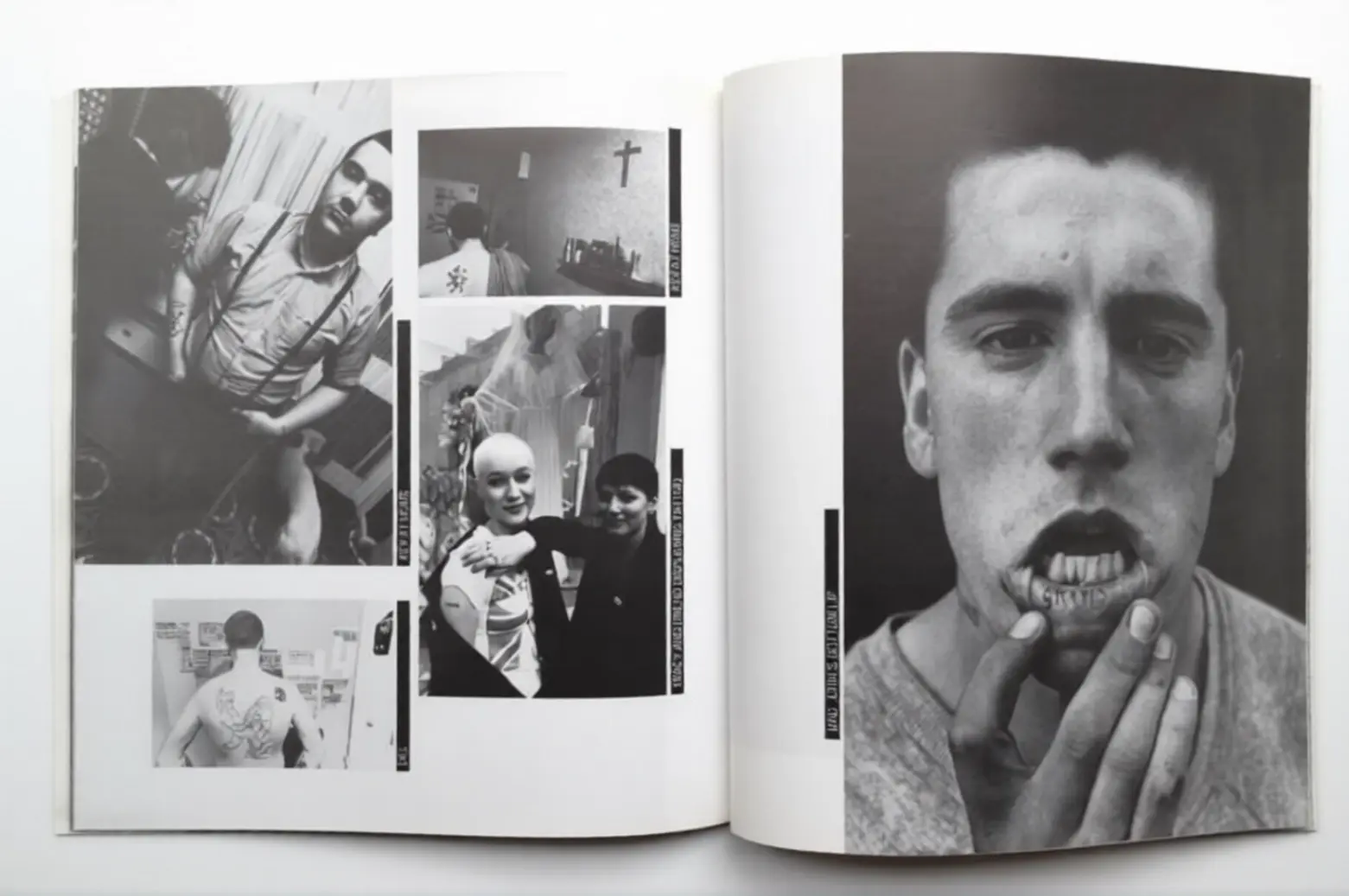

Nick Knight’s career did not begin in the polite corridors of fashion, but in the abrasive heat of subculture. His first book, Skinheads (1982), was not an attempt to aestheticise rebellion but to document it with disarming clarity. Even then, Knight displayed a sensitivity that contradicted the violence associated with his subjects: he photographed people, not stereotypes. It is this early mixture of empathy and confrontation that foreshadows everything he would later do in fashion.

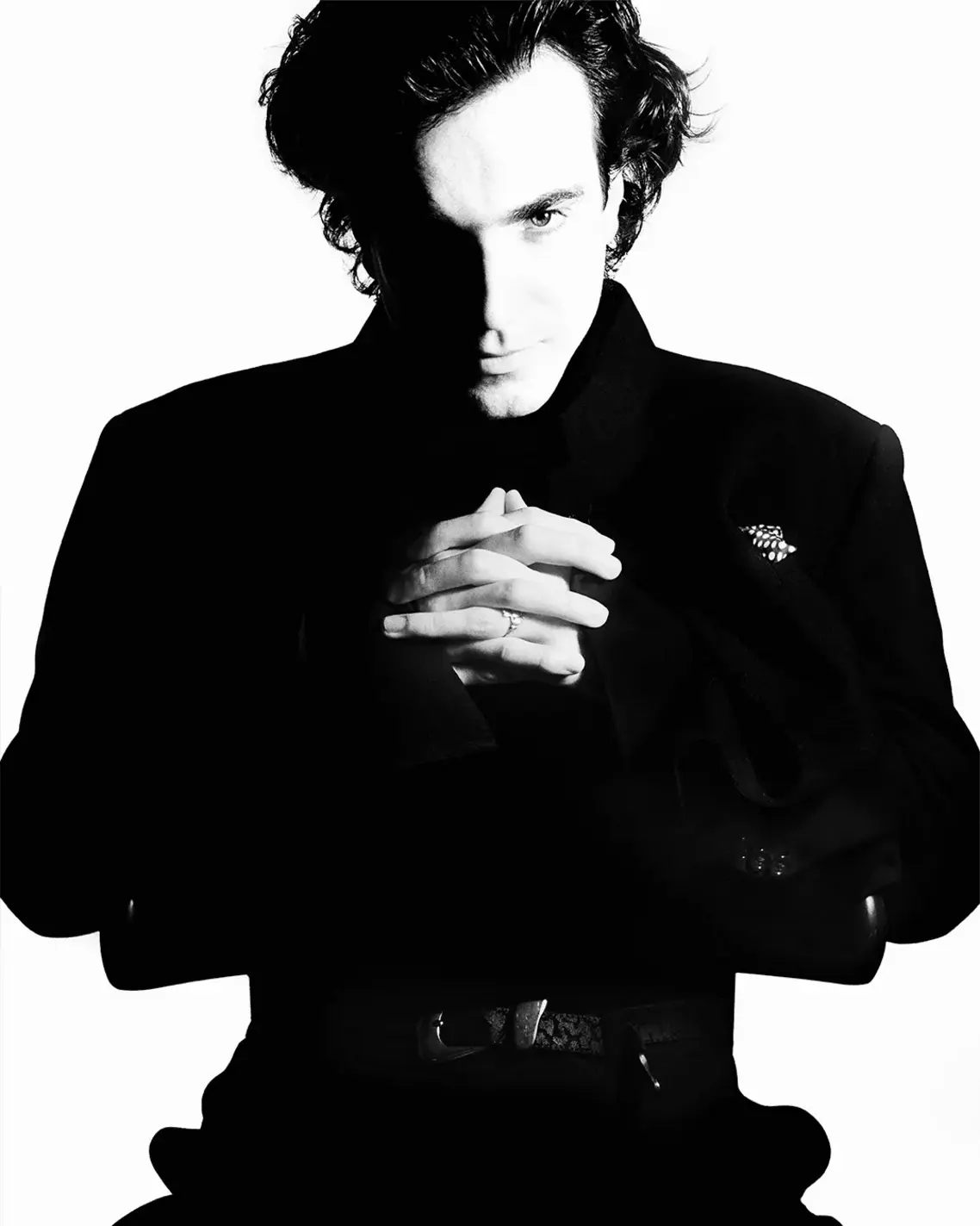

His real ascent began when i-D magazine recognised something in his work that the more traditional fashion press could not yet see: a visual insurgent with the ability to merge cultural currents into a new language. When Marc Ascoli brought him into the Yohji Yamamoto campaigns of the mid-1980s, alongside the incisive graphic sensibility of Peter Saville - it was immediately clear that Knight was no longer simply documenting the world; he was shaping the visual atmosphere around it. Those early black-and-white portraits did not merely showcase clothing; they captured the poetic tension of Yamamoto’s universe, the weight of fabric in motion, the melancholy in the models’ eyes. They signalled the arrival of someone who approached fashion with both anthropological detachment and feverish imagination.

What fascinates most about this origin chapter is how unplanned it appears. Knight arrived in fashion through the side door, without reverence for its rituals, and it is precisely this distance that allowed him to reimagine the medium so completely.

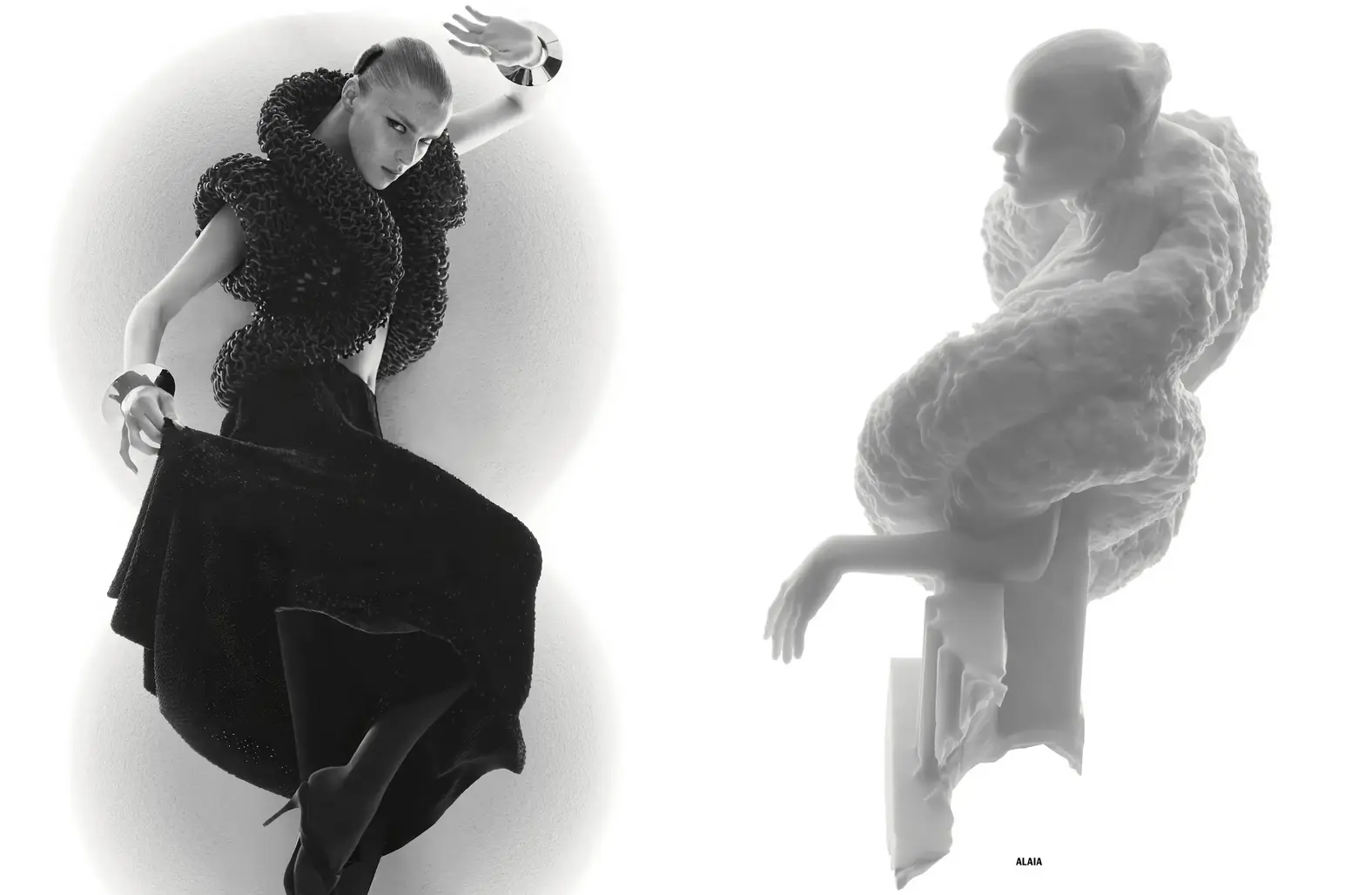

Nick Knight’s aesthetic has always carried the charge of something slightly unstable, as if each photograph were held together by a fragile tension between beauty and rupture. His images rarely aim for comfort. They glow with hazardous colours: acid yellows, metallic violets, bruised blues that feel less like hues and more like chemicals reacting on the surface of the paper. Knight has often insisted that he never intended to make “dark” photographs; he simply showed the world as it appeared to him. Yet his darkness is not emotional despair but atmospheric depth: a sculptural quality of shadow that gives his images an almost geological weight.

There is also an unmistakable sense of controlled chaos in his work. Knight approaches photography as though it were a laboratory experiment, calibrating each element: light, pigment, composition, until it reaches a point of volatile harmony. His fashion portraits, especially the ones produced in the 1990s and early 2000s, seem to crystallise the very moment before something breaks or transforms. A sleeve lifts like smoke, a face dissolves into abstraction, a dress becomes a moving force instead of a garment. His models appear both monumental and dissolving, as if caught in the middle of metamorphosis.

It is this exact push-and-pull - between control and eruption, between beauty and distortion - that gives Knight’s work its unmistakable emotional temperature. While other photographers romanticise, Knight destabilises. While others are perfect, Knight interrogates. His imagery does not seduce so much as it compels, almost demanding that the viewer confront the constructed nature of beauty itself.

SHOWstudio, launched in 2000, is perhaps Nick Knight’s most audacious and transformative achievement. It is not merely a website or a portfolio - it is a manifesto. Built on the radical belief that fashion should not be frozen as a static product but presented as a living, evolving performance, SHOWstudio prefigured a digital revolution that the industry would only later begin to embrace. Long before livestreams, digital-first editorial strategies, and social media dominated how fashion was consumed, Knight recognized that the real power of the medium lay not in the polished final image but in the messy, unmediated act of creation itself. He dared to show what magazines traditionally hid: the chaos, the uncertainty, the iterative labor, and the sparks of invention that make fashion both rigorous and thrilling.

SHOWstudio redefined authorship in fashion imagery. Knight invited designers, models, musicians, and audiences into a collaborative, performative space where creation was itself a spectacle. John Galliano cutting fabric in real time, Kate Moss performing in a cloud of powder, emerging designers sketching with trembling intensity in front of a live camera, these were not mere behind-the-scenes glimpses but deliberate, meaningful performances. They revealed vulnerability, exposed risk, and highlighted the alchemy that transforms ideas into objects. In my view, SHOWstudio marked the first time fashion could truly see itself, not as a perfected, aspirational reflection, but as a complex, flawed, human endeavor. The site made the audience complicit, turning passive spectators into witnesses of the labor, the intuition, and the genius that underlies each creation.

SHOWstudio transformed fashion from spectacle to dialogue. In my view, it marked the first time fashion saw its own reflection, not the glamorous one it preferred, but the more complex, imperfect, human reflection it tried so hard to avoid.

It is impossible to speak of Nick Knight without acknowledging his pioneering role in fashion film, a medium he embraced decades before it gained institutional recognition. Knight’s engagement with moving images began in the 1980s, when he filmed his shoots in a quiet, experimental way, anticipating the future before the tools and platforms existed to support it.

Knight’s films for Björk, Massive Attack, Lady Gaga, and Kanye West reveal a cinematic sensibility that is both an extension of his photographic practice and a radical reinvention of it. Clothing is transformed into a choreography of ideas, sound becomes architectural, and motion becomes a vessel for storytelling. His collaborations with John Galliano on the Maison Margiela projects, including S.W.A.L.K. and S.W.A.L.K. II, take this philosophy further still, transforming fashion film into an arena where ethics, memory, labor, and imagination collide. These works do not serve as mere promotional tools; they are immersive documents of the human, emotional, and intellectual labor embedded in couture, capturing subtleties - the tremor of scissors, the tension in a seamstress’s hands, the pause before a dress is revealed - that a still photograph alone could never convey.

What sets Knight apart as a filmmaker is his insistence that motion is not an embellishment but an essential evolution of fashion imagery. Where others might see film as a marketing accessory or a decorative extension of photography, Knight sees it as an inevitable expansion of his medium. In watching a Knight film, the viewer does not simply consume fashion - they inhabit it, experience it, and understand its complexities in ways that are both intellectually rigorous and emotionally profound.

Nick Knight’s significance in contemporary fashion extends far beyond his remarkable longevity. While many photographers, even the celebrated ones, fall back on nostalgia or cultivate repetitive signatures, Knight embodies a relentless restlessness. He has always sought the horizon of possibility, embracing technological innovation not as novelty but as a tool to rethink the very language of the image. From pioneering early digital film experiments to integrating CGI, 3D scanning, AI-generated models, and digital avatars, Knight has consistently anticipated the tools that would shape visual culture, rather than merely responding to them. His recent project, ikon-1, executed with the visionary Jazzelle Zanaughtti, demonstrates this prescience: it does not merely show fashion but it interrogates the human form itself, reframing it in a digital, malleable, almost post-human context.

What sets Knight apart is that this experimentation is never gratuitous. He does not innovate for spectacle or novelty; he does so in service of a deeper purpose. Knight insists that fashion imagery engage with the world as it is: chaotic, accelerated, fragmented, and perpetually transforming. He refuses to allow the photograph to remain a passive object of aesthetic pleasure. Instead, he demands that it interrogate, provoke, unsettle, and disclose truths about culture, identity, and power. In this way, each image is both a work of art and a site of discourse.

Somehow, Knight’s legacy is defined by this radical conviction: that fashion imagery is not mere decoration or aspirational ornamentation. It is a medium for intellectual, emotional, and cultural engagement - a space where beauty, technology, and ideology collide. Over four decades, Knight has forced the industry to confront this potential, often before it was willing to acknowledge it. He has made the photograph not just an object to be consumed, but an idea to be reckoned with.

Ultimately, Nick Knight has done more than redefine what a fashion photograph can look like. He has fundamentally redefined what it can mean. His work insists that the image, no matter how seductive or polished, is never neutral, and that fashion itself is always a site of possibility, confrontation, and reinvention. To encounter a Knight image is to be reminded that fashion, at its most vital, is not about comfort- it is about cognition, imagination, and provocation.