"He has elevated Italian elegance to the world stage" - Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH

"He has elevated Italian elegance to the world stage" - Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH

December 8, 2025

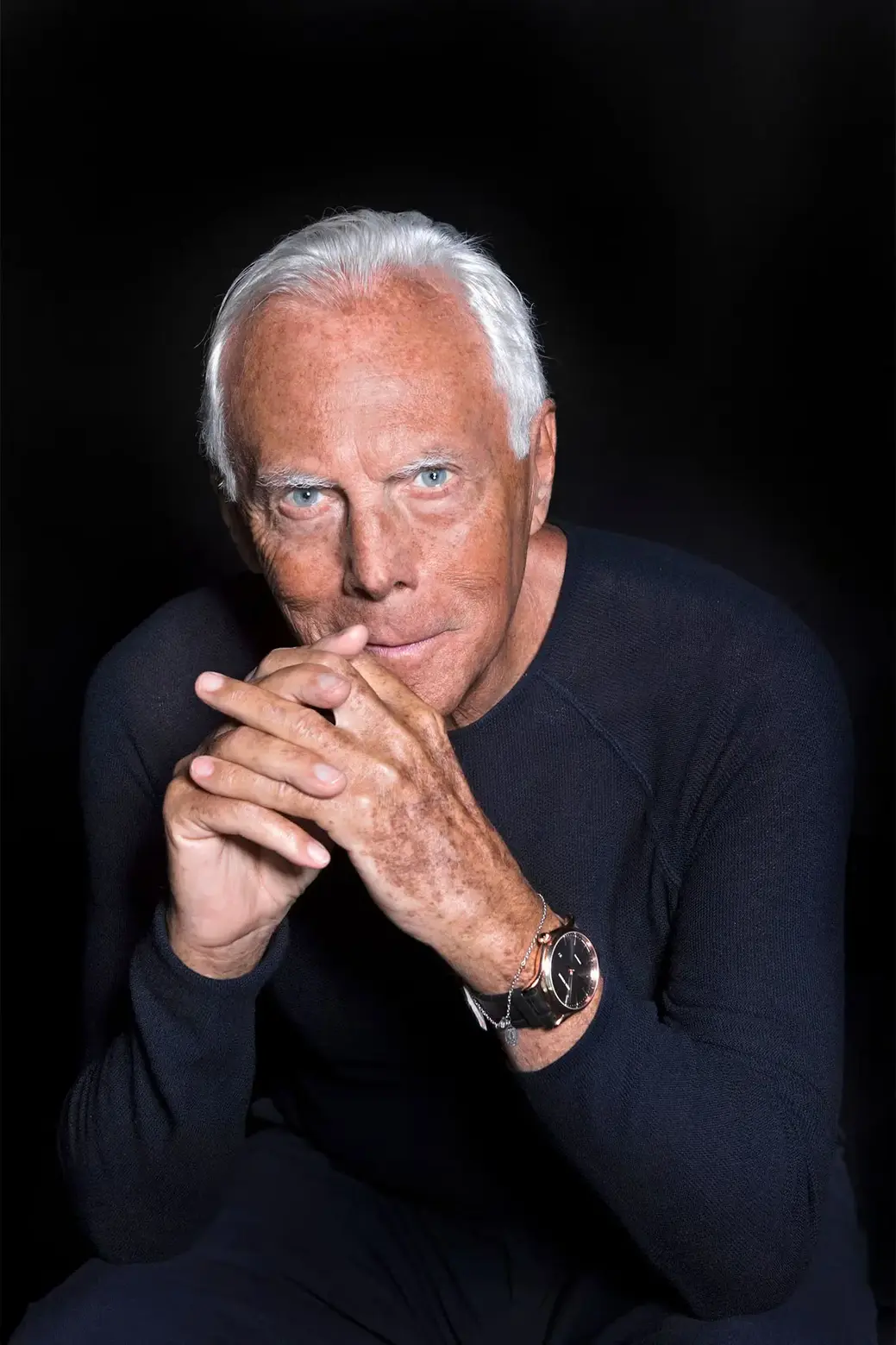

On 4 September 2025, the fashion world fell silent—then erupted in homage. Tributes flooded Instagram, Facebook, magazines, and newspapers, celebrating the life and legacy of Giorgio Armani. Designers, actors, and cultural figures who had worked with or been inspired by him expressed their grief and admiration. Ralph Lauren wrote, “I have always had the deepest respect and admiration for Giorgio Armani … his legacy will go on and on.” Donatella Versace posted simply, “The world lost a giant today. He made history and will be remembered forever.” Julia Roberts shared a photo of herself and Armani, captioned: “A true friend. A Legend.” Morgan Freeman reflected, “On screen and off, I have had the honour of wearing Armani. Today we remember a man whose genius touched many lives and whose legacy of grace and timeless style will endure.”

Beyond fashion, voices from film, sport, and politics joined in remembrance. The consensus was clear: with Armani’s passing, the industry had lost a guiding light - but his vision, elegance, and belief in subtle power remain woven into wardrobes and imaginations around the world.

In 1980, Richard Gere stood before a mirror in American Gigolo, caressing the fabric of his jacket with an almost sacred reverence. This cinematic moment did not just launch a thousand fashion fantasies; it announced the arrival of a new language in luxury, one spoken fluently by a former window dresser from Piacenza who had somehow cracked the code of modern elegance. While Coco Chanel freed women from corsets and Christian Dior cinched them back into New Looks, Armani did something arguably more radical: he made power comfortable. Not just physically comfortable, mind you, but psychologically liberating. He took the armour out of professional attire and replaced it with something far more subversive-confidence wrapped in cashmere.

"Perfectionism, and the need to always have new goals and achieve them, is a state of mind that brings profound meaning to life," Armani once observed, and this mantra became the backbone of an empire built on paradox: strength through softness, power through fluidity, revolution through restraint. Where others saw contradiction, Armani saw opportunity. His design philosophy was not about creating fashion. It was about eliminating friction between the body and its aspirations.

Born in 1934 into a world of rigid traditions and even more rigid tailoring, Armani emerged from the rubble of World War II with a visceral understanding that "not everything is glamorous." A childhood friend killed by unexploded ordnance, his own body scarred from the blast. These were not the typical origin stories of fashion royalty. Yet perhaps it was precisely this acquaintance with life's harder edges that enabled him to soften fashion's strictures so brilliantly. He knew what confinement felt like, and he spent his career liberating others from it.

While his contemporaries graduated from fashion academies with sketchbooks full of dreams, Armani earned his doctorate on the shop floor of La Rinascente, Milan's temple of commerce. For seven years, he dressed windows and studied customers like an anthropologist observing a fascinating tribe. He learned their secret desires not through whispered confessions but through the way their fingers lingered on certain fabrics, the subtle grimace when a jacket pulled across the shoulders, the sigh of relief when something finally fit not just the body but the life they imagined living.

This retail education proved more valuable than any atelier apprenticeship. When Nino Cerruti hired him in the 1960s, Armani arrived not with romantic notions about haute couture but with a merchant's understanding of what people actually wanted to wear. Within months, Cerruti asked him to restructure the entire company's approach. The medicine school dropout had become fashion's most unlikely diagnostician.

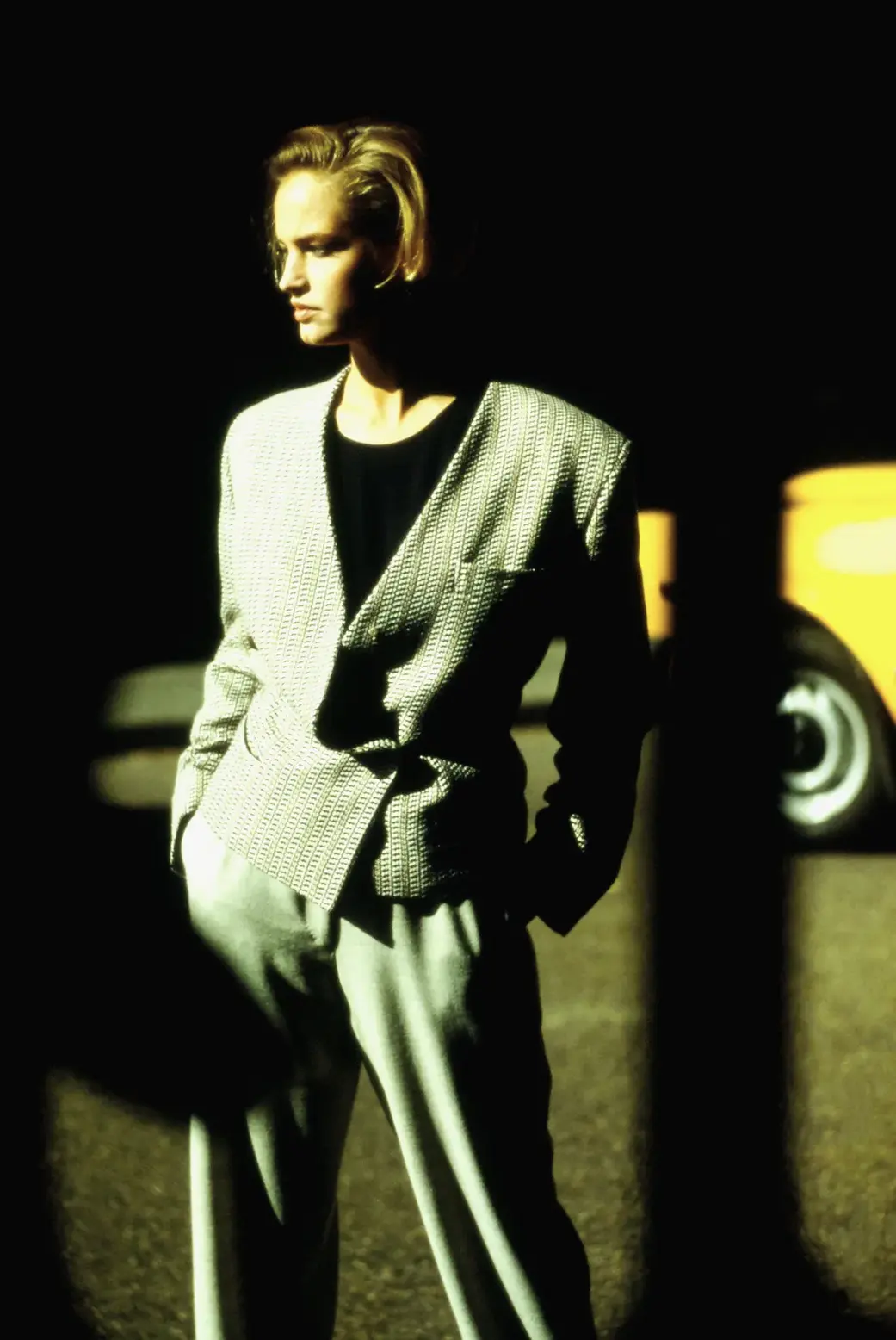

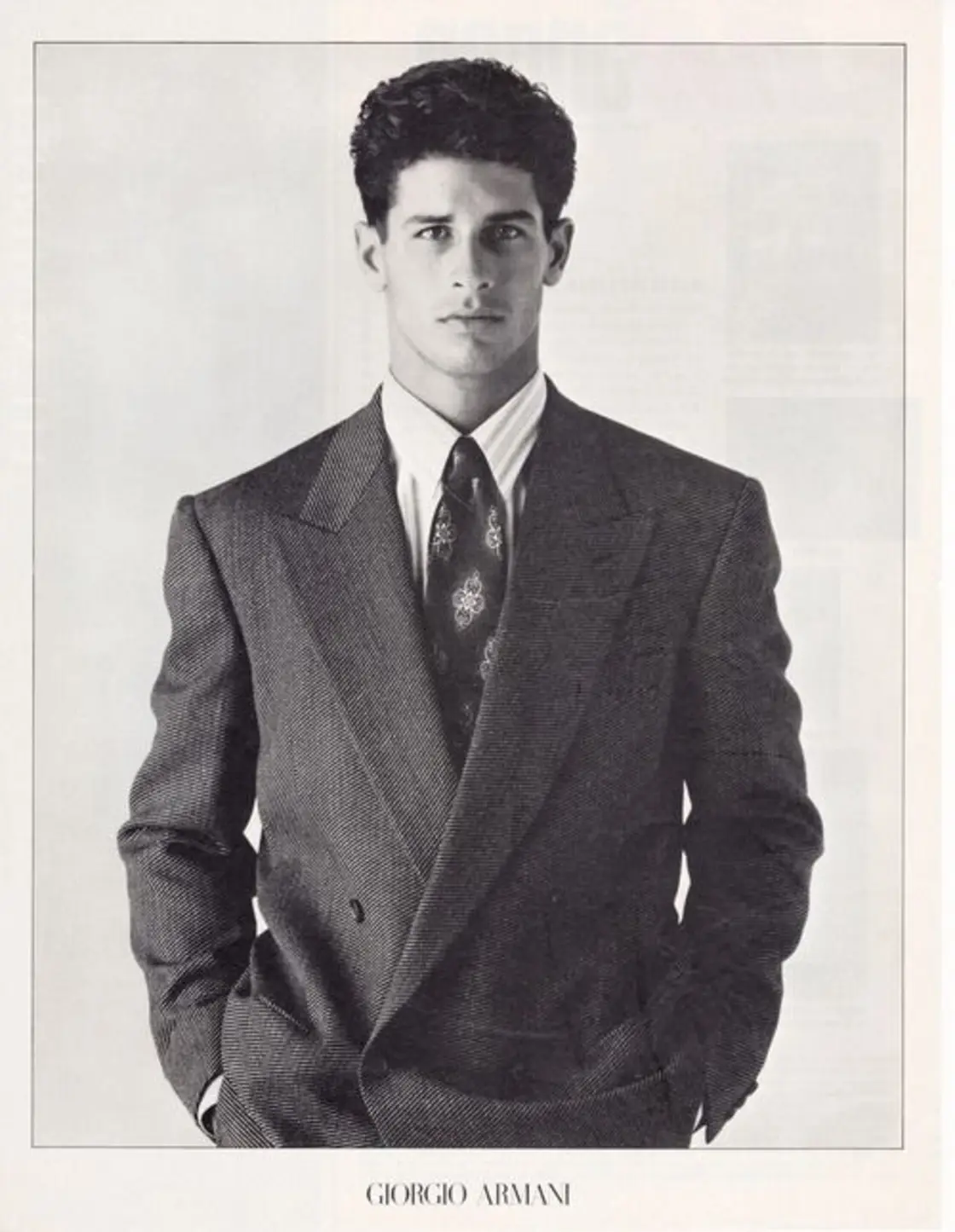

Giorgio Armani debuted his first ready-to-wear collection for men and women in Milan in October 1975 for the Spring/Summer 1976 season, introducing a radical new vision built on deconstructed tailoring, relaxed silhouettes, and quiet sophistication. Presented with just twelve models and a record player manned backstage by his partner Sergio Galeotti, the show closed with the models dancing - a subtle yet powerful declaration that clothing should move with life, not against it. The collection’s unstructured jackets, soft shoulders, and longer cuts redefined both menswear and womenswear, offering an alternative to the rigid, traditional suits of the era. Rather than impose, Armani’s tailoring suggested; it supported rather than constrained, whispering authority without shouting, and ultimately laid the foundation for a style philosophy that treated the body as a dynamic, intelligent form worthy of liberation.

If Coco Chanel freed women from corsets, Armani freed everyone from the tyranny of the perfectly pressed pleat. His ideology was not political in the traditional sense, but it was deeply democratic. He believed that elegance should not require suffering, that sophistication should not demand stiffness, that power dressing should not feel like a straight jacket.

"I realised that women needed a way to dress that was equivalent to that of men," he said, "something that would give them dignity in their work life." But rather than simply translating menswear into smaller sizes, he created a new vocabulary entirely. His power suits for women did not mimic masculine authority; they invented a new kind of power altogether: one that moved with feline grace through boardrooms and commanded respect without raising its voice.

This was fashion as social engineering. As women flooded into executive positions throughout the 1980s, they did so wearing Armani's soft-shouldered blazers that suggested competence without sacrificing sensuality. Men, meanwhile, discovered that strength could be supple, that masculinity could be tender. He did not just dress the changing times; he helped enable them.

When Diane Keaton ascended the Oscar stage in 1978 wearing an Armani jacket, she was announcing a new dress code for success, which promoted the Armani dynasty. Two years later, "American Gigolo" transformed Armani from designer to cultural force. The film was essentially a 117-minute advertisement for a lifestyle that did not yet exist but that everyone suddenly wanted. As Armani told The Economist’s 1843 magazine in 2017: “was a sensation: everybody wanted to know what Gere looked so great wearing. So it gave me a sudden positive notoriety.”

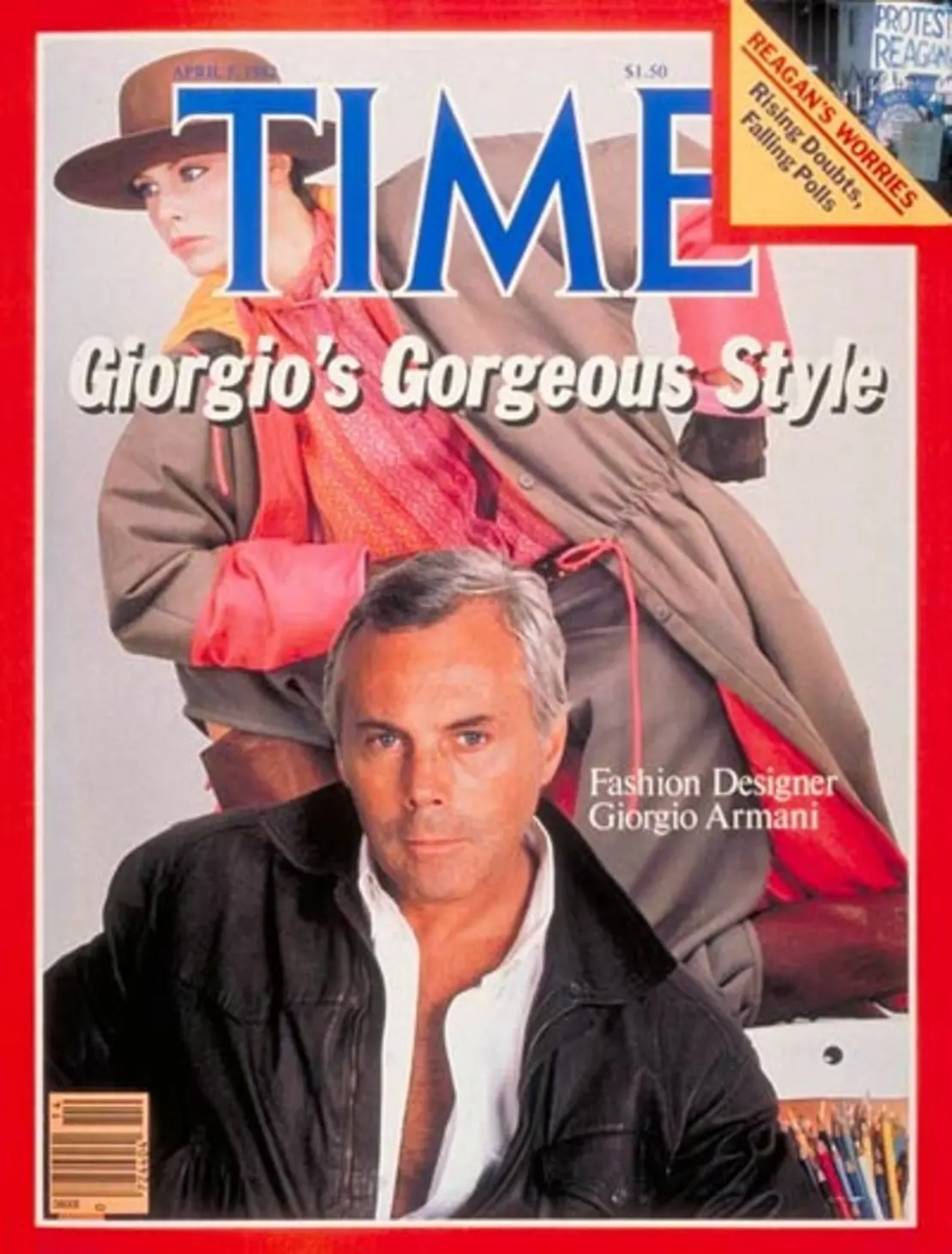

As the United States entered a high point of global influence in the 1980s, Giorgio Armani offered a refined counterpoint to traditional power dressing with his soft-toned, loose-shouldered, and effortlessly chic aesthetic. His launch of Emporio Armani and Armani Jeans made his style more accessible, rapidly cementing his place as the face of Italian fashion in the American imagination - second only to Gianni Versace in visibility. Armani’s rise was swift and cultural: a Time magazine cover in 1982, and soon after, his signature looks dominated the hit TV series Miami Vice.

In series, Don Johnson’s character Sonny Crockett revolutionized men's fashion with sockless loafers, pastel t-shirts, and unconstructed linen suits - an aesthetic shaped largely by Giorgio Armani. Armani's relaxed tailoring replaced stiff business attire with a softer, modern silhouette that felt both casual and refined. The show’s popularity propelled this new look into the mainstream, making dark, structured suits seem outdated, much like spats from a bygone era. This cultural shift not only modernized businesswear but also cemented Armani as the global symbol of timeless elegance and effortless sophistication.

For The Untouchables (1987), Giorgio Armani deliberately reimagined 1930s fashion, rejecting period accuracy for his signature modern tailoring. He introduced sophisticated, waist-cinched suits with wide shoulders, creating a stark contrast to the film's gritty setting. This vision not only defined character evolution, like Eliot Ness's sharpening style, but also fused Prohibition-era Chicago with 1980s elegance, proving the timeless power of his design philosophy.

Though the 1980s defined his brand, Armani’s influence only deepened in the 1990s. In 1990, he introduced “The Natural,” a three-button, narrow-shouldered yet soft version of the sack suit that shaped menswear for years, unfazed by competition from rising names like Prada and Calvin Klein. That same year, the documentary "Made in Milan", edited by Martin Scorsese, captured Armani at work and his design ethos in his own words: “Society changes and I change with it. I try to filter my ideas through a daily reality.”

Unlike many of his contemporaries who licensed their names freely, Giorgio Armani built his empire with disciplined control, managing every aspect of production and distribution with the precision of a Milanese Medici. His 1978 partnership with manufacturer GFT allowed him to scale without surrendering creative sovereignty, while labels like Emporio Armani and Armani Jeans made his vision more accessible without diluting its essence. As his name expanded into hotels and lifestyle ventures, most notably in Dubai - Armani evolved from designer to global brand, a philosophy, even an adjective.

Despite repeated offers from private equity and luxury conglomerates, he remained fiercely independent. He once recalled a meeting where, after listening silently, Italy’s most powerful banker told the investors, “Mr. Armani doesn’t need us. Let’s go.” Control, not capital, was Armani’s true currency. Forbes would later estimate his fortune at $13 billion, but for the man who launched his brand by selling a Volkswagen Beetle, the real success was building a fashion empire that answered only to himself.

Armani's true genius lay not in what he added but in what he removed. His palette, those famous greiges, beiges, and navy blues, was not absence of color but presence of subtlety. In an industry that often mistakes noise for innovation, he proved that whispers could be more powerful than screams.

His personal aesthetic reflected this philosophy of elegant austerity. The swimming pool at his home, 50 yards long but only one yard wide, became legendary as a metaphor for his approach: everything reduced to its essential purpose, nothing wasted on mere display. Even his rare admissions, taking LSD once, getting drunk a single time, suggested a man who had tried excess and found it wanting.

When illness prevented him from attending his spring 2026 shows, Armani supervised every look by phone, still the exacting maestro even in his tenth decade. His dedication bordered on the monastic—those dawn swims in his narrow pool, the notorious discipline that New York Magazine described as "self-control and self-containedness that can come off as coolness."

Yet coolness implies detachment, and Armani was anything but detached. He was instead ferociously present, forever adjusting a lapel, reconsidering a button, pursuing what he called his "obsessive search for perfection." When Anna Wintour allegedly declared "the Armani era is over" in 2014, she misunderstood something fundamental: Armani was never about eras. He was about evolution, about the continuous refinement of an idea until it achieved its platonic ideal.

Giorgio Armani's legacy is not measured in hemlines raised or lowered, in seasons won or lost. It is found in every woman who strides into a boardroom feeling both powerful and feminine, in every man who discovers that gentleness and strength are not opposites. He did not just change fashion; he changed the physics of it, proving that soft power could be the strongest force of all.

His design motto might have been "eliminate the superfluous," but his life's work was about addition through subtraction - adding freedom by subtracting structure, adding confidence by removing constriction, adding beauty by eliminating the effort it once required. In the end, Giorgio Armani designed a new way of moving through the world: one where elegance was a birthright, not a burden, where sophistication came not from suffering but from the radical act of feeling comfortable in one's own skin - even if that skin happened to be wrapped in the world's most perfectly imperfect suit.