She freed women; he dressed them in dreams. Welcome to the fiercest fashion feud of the 20th century!

She freed women; he dressed them in dreams. Welcome to the fiercest fashion feud of the 20th century!

November 25, 2025

In the glittering world of haute couture, where ego is often as meticulously constructed as a gown, the post-war feud between Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and Christian Dior remains the industry’s most deliciously barbed and ideological clash. It was a battle fought not just with fabric and thread, but with withering quotes that have echoed through decades. At its heart was a simple, profound question: what is a modern woman meant to wear?

The year was 1947. Paris, still shaking off the dust of war and occupation, was gripped by a different kind of revolution. In a salon on the Avenue Montaigne, Christian Dior presented his first collection, “Corolle”. The press, weary of years of fabric rationing and utilitarian uniforms, Haper Bazard dubbed it the “New Look.” Overnight, Dior’s vision, a dramatic silhouette featuring a cinched waist, a soft bosom lifted by a built-in corset, and a skirt that used a lavish 20 yards of fabric whic redefined femininity.

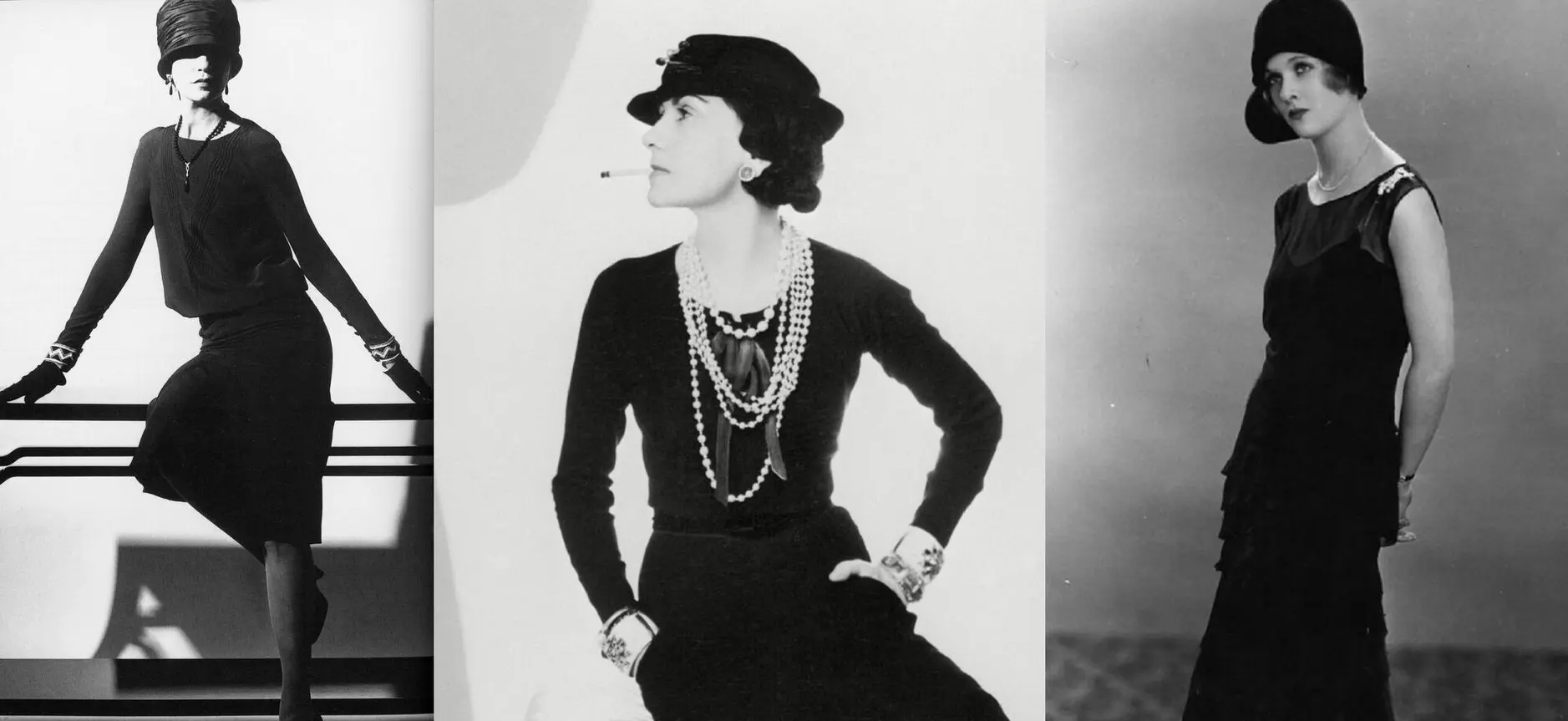

Chanel, then 64 and twenty-two years Dior’s senior, had spent her career liberating women from the corset. She saw Dior’s constructive designs as a betrayal of everything she had fought for. She launched a verbal offensive from her suite at the Ritz: a woman in a Dior dress, she declared, looked like "an old armchair". She saw his designs as a regression, a grotesque parody of femininity. In her view, he understood nothing of the women he dressed. "They are wearing the clothes of a man who does not understand women" she proclaimed. Her accusation was severe: Dior was reducing women to objects, wrapping them in fabric to be admired and possessed, dragging them back to a 19th-century ideal.

Dior, by all accounts, was the restrained gentleman to Chanel’s brilliant provocateur. He rarely engaged in public rebuttals, choosing instead to let his work speak for him. His response to the criticism was philosophical and articulate. He saw his craft as “like designing a temporary architectural work, to honor the beauty of the female body”. Where Chanel championed pragmatism, Dior championed fantasy. He famously confessed, “I do not like pragmatism, what I like is an elegant fashion dream". This was no empty boast because some of his elaborate evening gowns weighed up to 27 kilograms, a testament to his commitment to breathtaking, albeit burdensome, elegance.

The feud was a schism in fashion philosophy. To Chanel, her goal was liberation. Her clothes were for doing, moving, and living which tools for independence. Whereas, Dior catered to a pent-up desire for luxury and glamour, offering an escape into a meticulously crafted dream. This ideological war even crossed the Atlantic. When Dior took his collection to the pragmatic United States later in 1947, he was met by picketers, largely Chanel supporters, brandishing signs that read “Mr. Dior, We Abhor Dresses to the Floor!” The controversy grew so heated that Time Magazine felt compelled to conduct a formal poll, asking its readers: “Do you support or hate 'The New Look'?”

Even other designers were not spared Chanel’s wrath. She lumped Dior together with Cristóbal Balenciaga, dismissing their designs as "illogical”and faulting them for failing to truly honor the female form.

Yet, for all her vitriol, Dior acknowledged her influence with grace. In his memoirs, he wrote that “Chanel's personality and taste were distinctive, authoritative and elegant,” a stunningly diplomatic tribute to his fiercest critic.

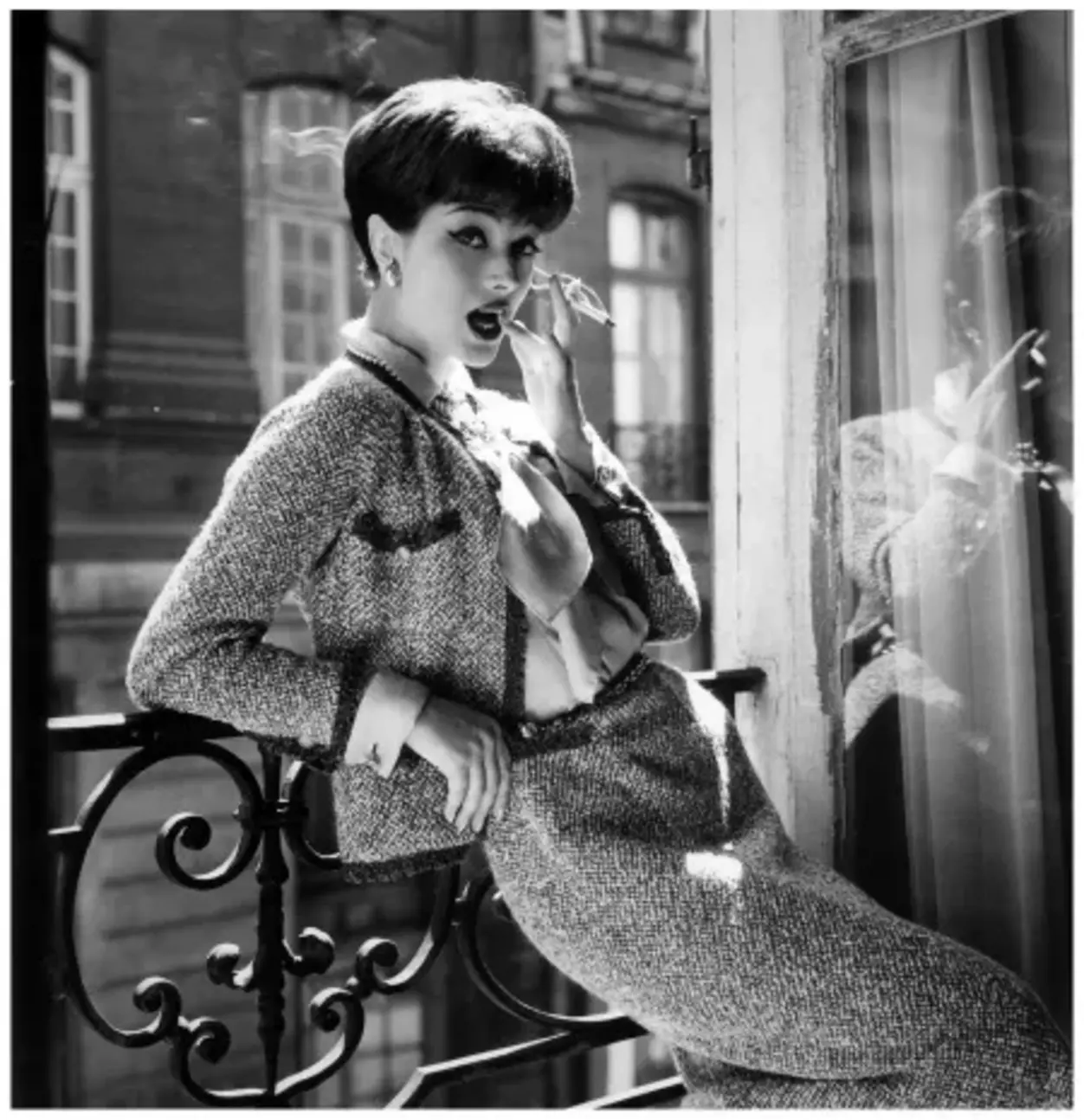

The irony, of course, is that history has vindicated them both. Chanel understood the woman who needs to conquer the world. Chanel gave women the uniform for their daily conquests - the little black dress, the tailored suit, clothes for "doing". Dior offered the armor for their dreams - the breathtaking ballgown, clothes for "being". One empowered through practicality, the other through enchantment. Today, the two houses stand as pillars of French fashion, a permanent testament to a glorious, irreconcilable difference of vision, proof that while one woman’s dream gown is another’s old armchair. There is room in every wardrobe for both.