How easy is it to fool you?

How easy is it to fool you?

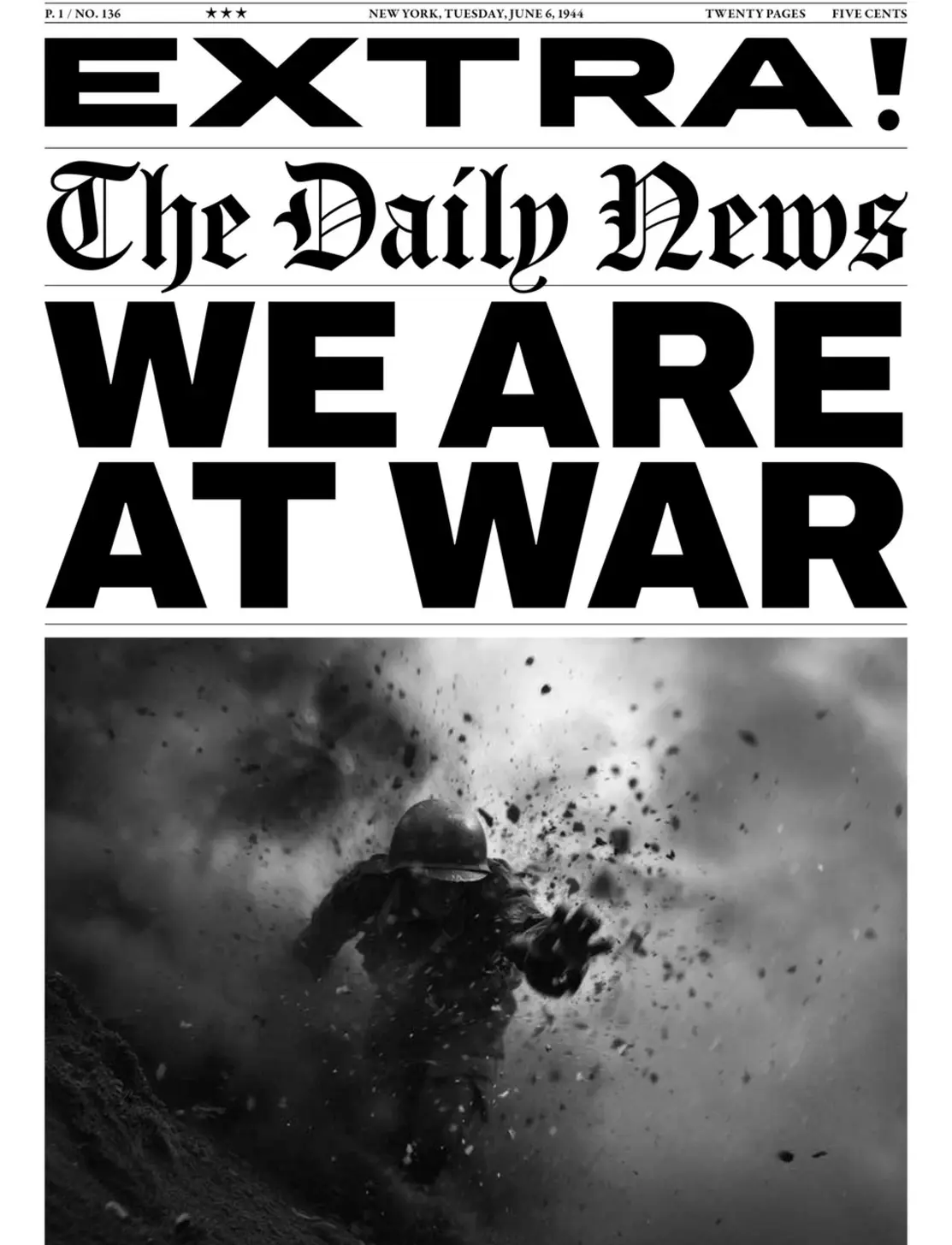

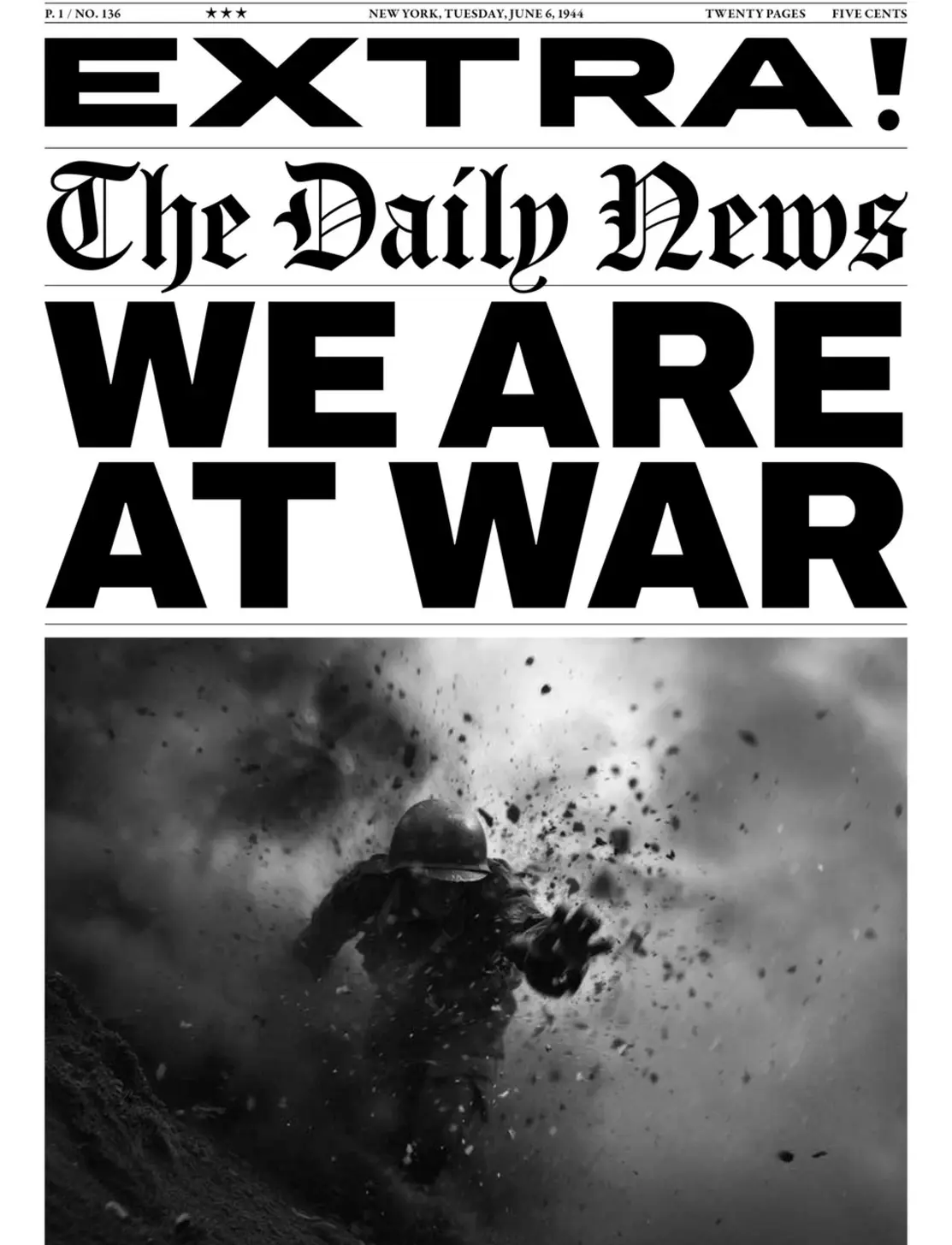

In a provocative new exhibition, artist Phillip Toledano employs AI-generated images of World War II to probe our fragile grasp of truth.

The walls of the Deauville Photography Festival in Normandy are lined with what appear to be newly unearthed, haunting photographs by Robert Capa, the celebrated war correspondent whose lens defined much of World War II photography.

Visitors pause before scenes they believe to be recovered images from the D-Day landings — a moment in which Capa was famously the only photojournalist on the beach. The tragedy of that day’s record is well known: most of Capa’s original negatives were destroyed in a London darkroom accident. Now, it seems, those lost images have been miraculously restored.

But as the exhibition unfolds, a jolt awaits. Not one of the images is real. Toledano, a New York-based British artist, has not recovered history — he has invented it. Using artificial intelligence in photography, he has rendered hyper-realistic visions of the past that never existed. His intent is disarmingly simple: to make viewers just a little uneasy.

“We’re at this historical, cultural hinge point where our relationship with images is being fundamentally altered,” Phillip Toledano said. By choosing a historical event that is universally recognized, and by invoking an almost biblical figure in photography, he hopes to force an audience to confront just how convincingly the past can be rewritten. “If you can reinvent the past so persuasively,” he added, “imagine what you can do with the present.”

Photographic deception is nearly as old as the medium itself. In 1917, even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, was captivated by the Cottingley Fairies hoax, a set of photographs staged by two young cousins that purported to show fairies in an English garden. Long before AI photography, images were already tools of illusion.

In the modern era, tools like Photoshop reshaped magazine imagery, smoothing wrinkles and manufacturing visual perfection. The difference today lies in speed and scale. Where manipulation once required skill and intent, AI-generated images can now be produced in seconds, often indistinguishable from documentary photography.

The difference today is speed and accessibility. Where manipulation once required skill, time and specialized equipment, modern AI can fabricate convincing images in seconds. The cost of entry has collapsed to near zero. And in an age where social media accelerates the spread of images globally, fakes can circulate long before they are identified—if they ever are.

“Photography used to be the central arbiter of image as truth,” Toledano said. “Now, there’s a technology that destroys that entirely.” In this new landscape, photography and truth are no longer inseparable.

The distinction between the real and the fabricated is already eroding. A University of Warwick study found that people could correctly identify AI-generated images only 65 percent of the time. More unsettling, participants often judged AI-generated faces to be more attractive and more trustworthy than real ones. Other research has shown that fabricated images can implant false memories of events that never happened.

The consequences are already visible. An AI-generated image of Pope Francis wearing a white Balenciaga puffer jacket spread globally before being debunked. Conversely, authentic photographs are now frequently dismissed as fake — a reversal that undermines journalism, evidence, and collective memory.

The erosion of trust extends beyond art. Artificial intelligence in photography now shapes personal identity, politics, and legal systems. Editing apps alter self-perception; deepfakes threaten public discourse.

Bryan Neumeister, chief executive of USA Forensic, works to verify images presented in high-profile legal cases, including the 2022 trial between Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, and in government assessments of hostage photographs. “People don’t vet much of what they see,” he said. “When you know that people don’t have the time or motivation to check, AI-generated images become a powerful weapon.” The danger is heightened, he added, when a “bad fake” appears credible on a small cellphone screen.

Efforts to regulate the technology are nascent. This year, the European Union enacted the first AI laws, requiring companies to label altered images. Critics dismiss the measure as insufficient. Proposals range from restricting AI’s ability to simulate news events to embedding indelible watermarks. Yet, as Neumeister noted, “any technological fix will be met with a technological workaround.”

Toledano offers a more unsettling answer: perhaps we should abandon the expectation that photography conveys objective fact. “If photography ever was trustworthy, now we have to learn not to trust,” he said. On the long scale of human history, he argues, photography as truth has been a fleeting exception. “Now we’re returning to the default setting—which is not having any clue.”

The idea recalls the philosopher Vilém Flusser, who argued that in an image-saturated age, we no longer read pictures as representations of reality. Instead, we experience reality as a sequence of images. A place becomes real only once it has been photographed—and posted.

While our culture may be adapting to this shift, Toledano insists on vigilance. “We do have to think about these things more,” he said. The alternative, he warns, is a future defined by corrosive uncertainty. “We can’t be in a place where we’re constantly wondering: is that the president in that picture, or not? Who knows? How can we tell?”