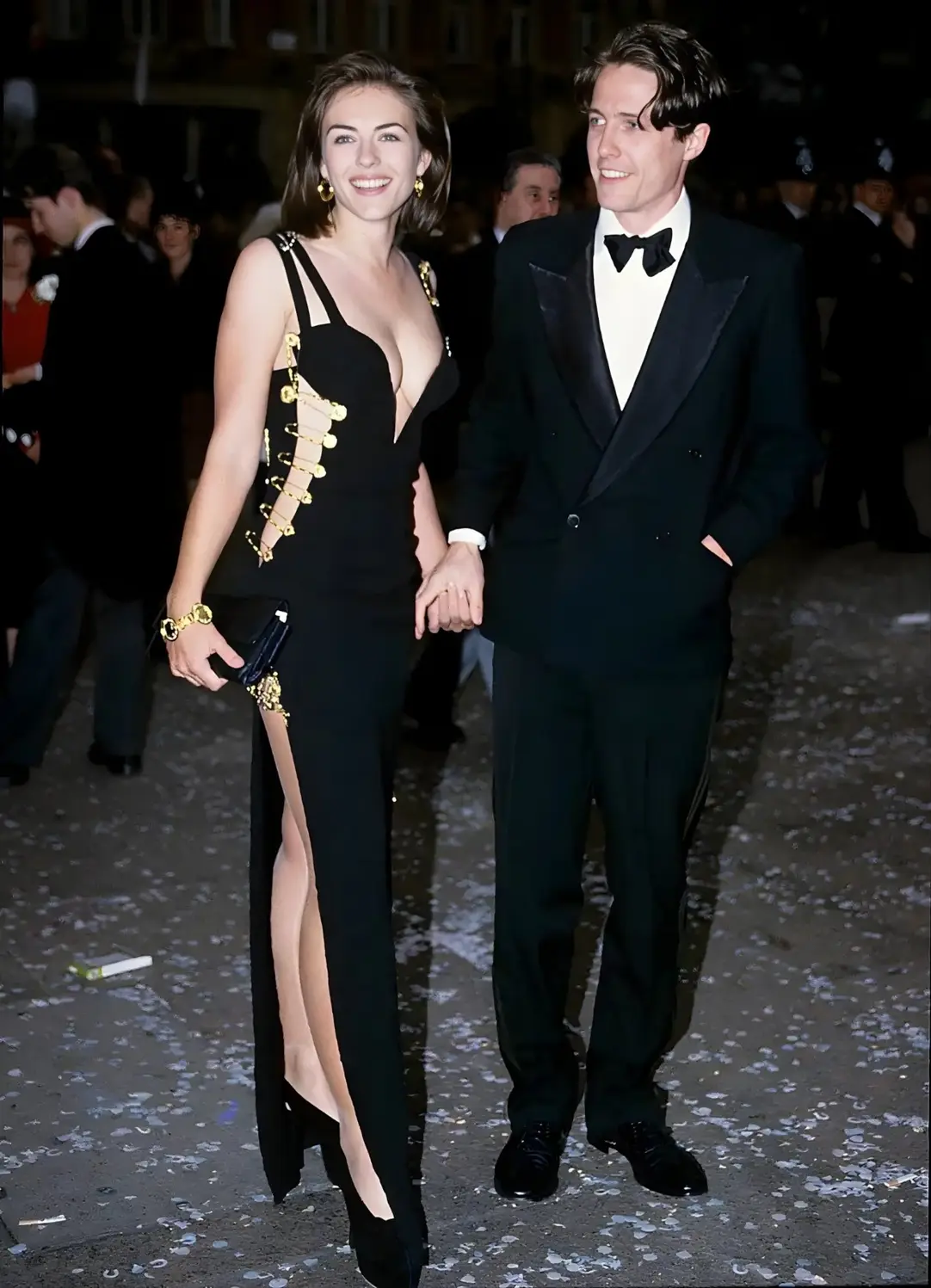

On May 11, 1994, the UK premiere of Four Weddings and a Funeral lit up Leicester Square, yet the image that travelled fastest belonged to someone who was barely a public figure at the time, Elizabeth Hurley.

On May 11, 1994, the UK premiere of Four Weddings and a Funeral lit up Leicester Square, yet the image that travelled fastest belonged to someone who was barely a public figure at the time, Elizabeth Hurley.

May 11, 2025

Elizabeth Hurley, arriving alongside Hugh Grant, wore a black Gianni Versace gown held together with oversized gold safety pins, and the red carpet gained a new kind of electricity: fashion that felt risky, sharp, and instantly unforgettable.

The dress worked like a headline you could wear. Its power came from contradiction. The silhouette read sleek and controlled, then the cutouts and hardware introduced a sense of danger, like the garment had been engineered at the edge of coming undone. Those pins did more than fasten fabric. They created tension, they drew the eye, they made the construction part of the story. In one look, Versace turned lingerie-level boldness into couture-level confidence, then Elizabeth Hurley turned that confidence into a cultural moment.

Elizabeth Hurley’s own origin story for the night makes the moment even sharper. She has recalled scrambling for something to wear, with top houses declining to lend outfits because they did not know who she was. Then Versace said yes. The dress arrived with a kind of blunt magic, pulled from a bag, worn with instinct, then launched into history. That mix of last-minute chaos and perfect impact still feels modern, the template for “overnight style icon” narratives that social media now manufactures daily.

There is also craft under the drama. Elizabeth Hurley later emphasized how securely the gown was built, despite the illusion of peril, praising the structure and fit. She wore it once, returned it the next day, and joked later that the dress went on to live its own life through exhibitions and tours. In other words, the garment became an artifact, not just an outfit.

Why did it make her famous? Because it condensed three forces into a single frame.

First, it turned the “plus-one” into the headline, shifting the red carpet’s hierarchy overnight.

Second, it showed how a designer’s signature can read at a glance: Versace’s body-skimming black, punctured with gold, built to command cameras.

Third, it proved that fashion could generate publicity equal to film, sometimes greater.