For anyone who has ever flipped over the glossy press card tucked inside a new fragrance box, the story always looks the same: a sparkling citrus opening, a heart of lush florals, and a base of something warm, musky, or woody.

For anyone who has ever flipped over the glossy press card tucked inside a new fragrance box, the story always looks the same: a sparkling citrus opening, a heart of lush florals, and a base of something warm, musky, or woody.

September 19, 2025

For anyone who has ever flipped over the glossy press card tucked inside a new fragrance box, the story always looks the same: a sparkling citrus opening, a heart of lush florals, and a base of something warm, musky, or woody.

It is the so-called pyramid structure, a neat diagram that’s dominated perfume marketing since the mid-20th century. But let’s be honest: when was the last time a scent actually unfolded on your skin like a three-act play? The answer: not as often as brands would you believe.

The pyramid is more marketing shorthand than a scientific truth. Top notes are described as bright and airy, the middle as romantic and floral, the base as deep and grounding. And sure, this model works—sometimes. But in 2025, the perfume landscape is far more complicated, more diverse, and infinitely more interesting.

Take Chanel’s Les Exclusifs Sycomore Eau de Parfum. The house describes it with a clear wood-smoke narrative, but from the first spritz, you’re enveloped in a smoky vetiver haze that doesn’t wait politely at the base - it hits right away, evolving in waves instead of layers. Or Maison Francis Kurkdjian’s Baccarat Rouge 540, the modern cult phenomenon. Its amber-floral-woody profile doesn’t neatly separate into top, middle, and base. It’s linear, persistent, and instantly recognizable - less like a pyramid and more like a neon light glowing without dimming.

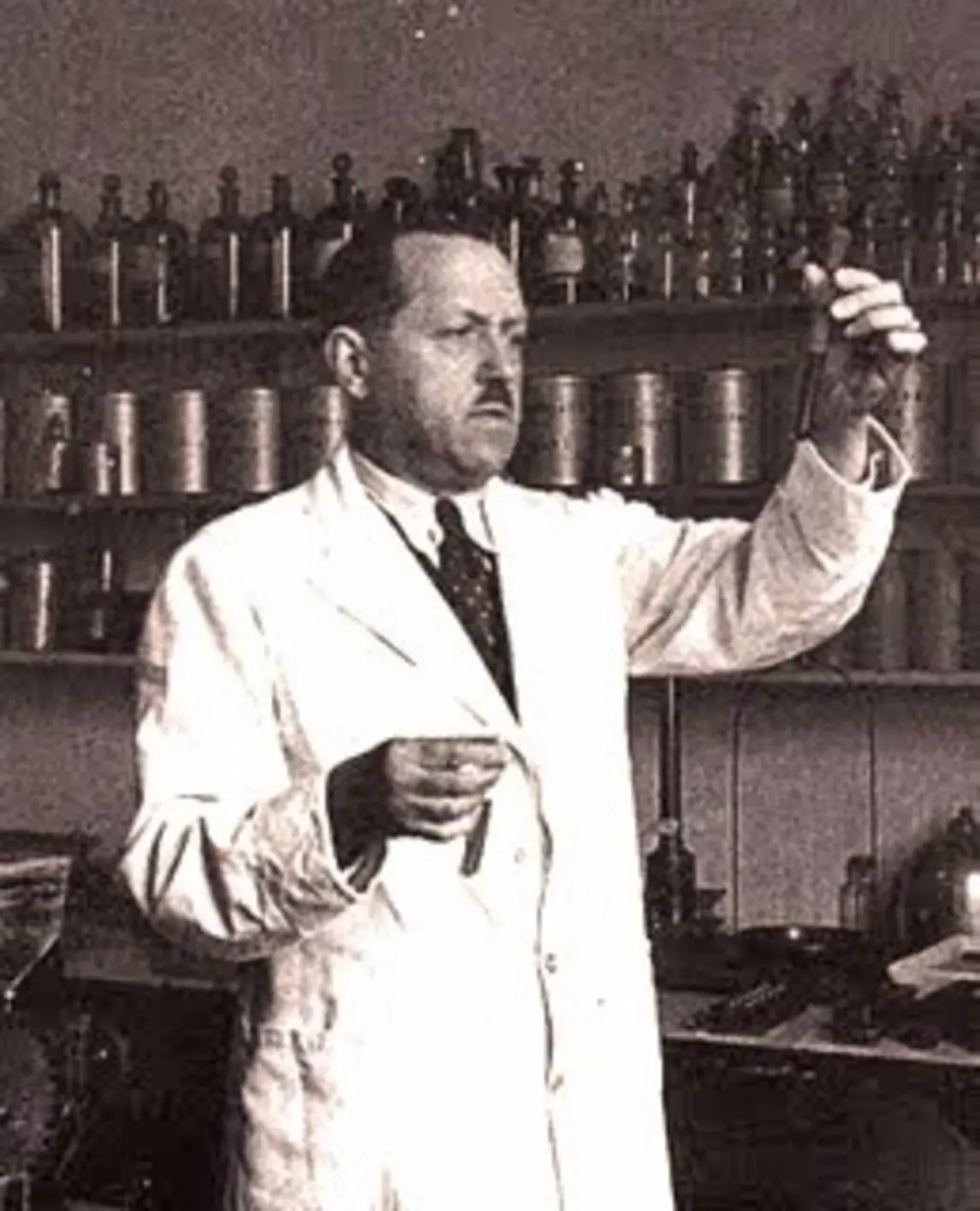

The pyramid structure was codified by perfumer Jean Carles in the mid-20th century, and in that era, it made sense. Carles, who created classics like Dana Tabu (1932) and Carven’s Ma Griffe (1946), lost much of his sense of smell later in life. To compensate, he devised the “Jean Carles Method,” a systematic approach to fragrance construction. Remarkably, he continued to create perfumes using this method even after losing much of his sense of smell, training perfumers to imagine a fragrance before mixing it, a principle still taught in perfumery schools today.

Think of Dior’s Miss Dior (1947) or Dana Tabu (1932)—fragrances that felt architectural, meticulously built from sparkling top to velvety base.

But if you look further back, the story shifts. Guerlain’s Shalimar (1925), for example, doesn’t follow the pyramid. It’s a swirl of bergamot, vanilla, and musks that diffuse in unison, like brushstrokes blending into one another.

Modern perfumery borrows more from this earlier idea - less structure, more emotion. Which is why comparing eras matters: Lancôme Trésor (1990) introduced a linear model that carried one main accord throughout. Today, many perfumers lean into that approach because it resonates with the way we live, spritz, and swipe.

So what does fragrance look like in 2025? Often, it’s about immediacy. We’re a culture used to short-form video, to trailers that summarize an entire film in 90 seconds. Perfume is no different. We want to know within a single spray whether a scent feels like us.

That’s why perfumes like Dior’s L’Or de J’Adore (2023) and Tom Ford’s Myrrhe Mystère (2023) don’t bother with slow unfurling pyramids. The first is a molten, almost liquid gold interpretation of white florals that bursts with richness from the opening. The second delivers resinous, smoky mystery right out of the gate—no waiting for a base note to anchor it.

Meanwhile, niche houses are pushing structures even further. Byredo’s Mixed Emotions doesn’t feel like top-heart-base at all; it’s an olfactory collage of tea, mate, and birch woods. Le Labo’s Another 13 works in transparency, layering ambroxan with synthetic musks in a way that feels almost like scent in HD.

And then there’s the language. Notes like iced rose petals or luminous jasmine? They’re often marketing poetry for plain rose and jasmine. Sometimes, a “cashmere wood” base is actually just Cashmeran, a synthetic musk that reveals itself immediately rather than sitting quietly at the foundation. The modern consumer is savvy enough to know that these terms are shorthand, not chemistry lessons.

That’s where skin comes in. The only true way to decode a fragrance is to wear it—let it mingle with your body heat, your environment, your day. Because what reads as powdery iris on a blotter may translate as warm suede on your wrist.

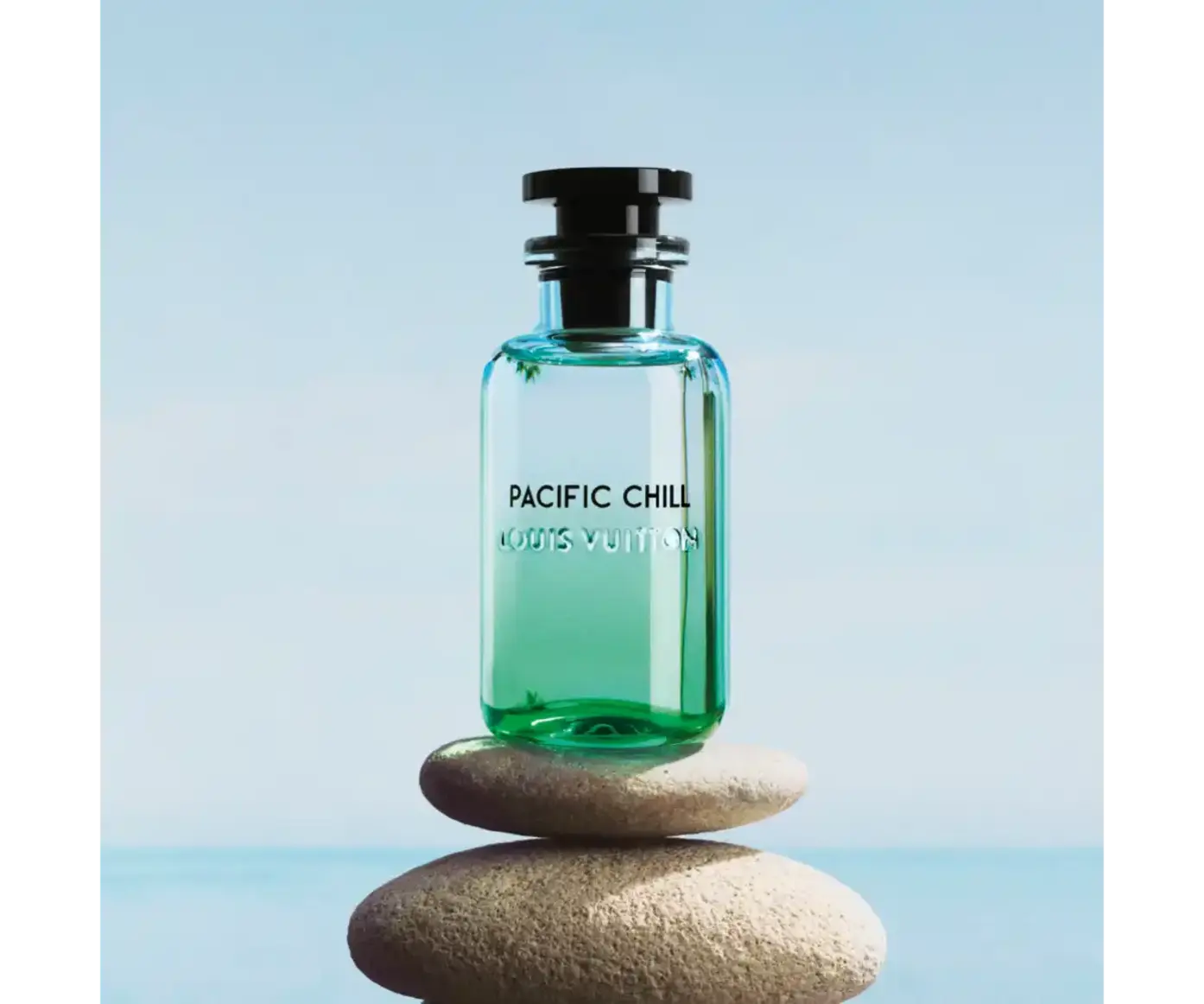

What’s exciting now is how high-end houses are reinventing fragrance storytelling altogether. Louis Vuitton’s Pacific Chill (2023) feels more like wellness in a bottle than a structured pyramid, with its burst of citrus and herbs that never “settle” into anything but stay endlessly bright. Prada Paradoxe Intense (2023) twists the pyramid into a paradox, amplifying both freshness and depth simultaneously.

And at the most rarefied tier, perfumes are becoming experiential. Guerlain’s L’Art & La Matière collection—scents like Oud Khôl or Patchouli Ardent—operate more like olfactory sculptures, where each note is present at once, shifting depending on how you move. Clive Christian’s Crown Collection works in bold strokes, meant to project authority rather than evolve delicately.

Perfume has never been just about formulas. It’s about art, emotion, memory—and yes, sometimes marketing myth. The pyramid structure still has its place, but today’s fragrances are more fluid, more immediate, and more daring. The best advice? Ignore the diagram, skip the press release, and let your skin do the storytelling.

Because a great perfume doesn’t just reveal itself in stages. It reveals you.